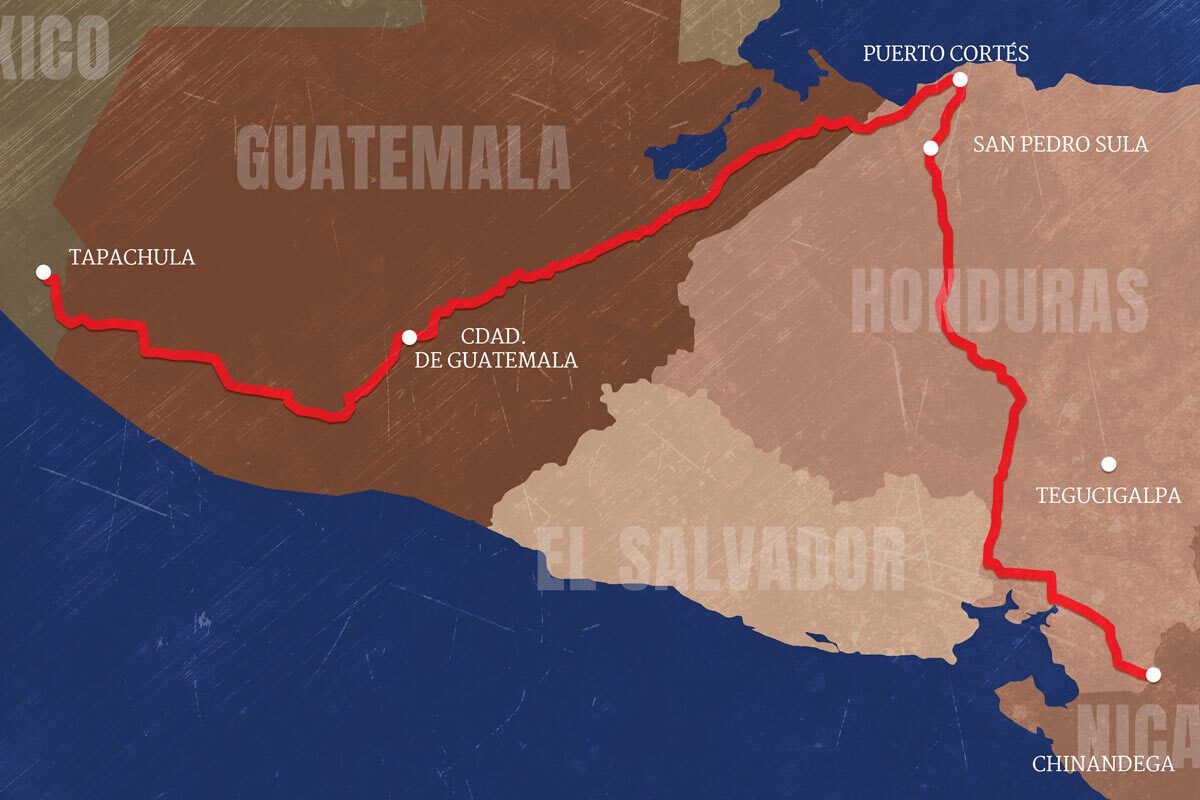

Washington’s new immigration changes, such as humanitarian parole, have reduced the number of Nicaraguans trying to cross the southern U.S. border irregularly, but at the same time have imposed a new reality, those who are stranded in two key cities in Mexico: Tapachula and Matamoros, the first a trap and the second a filter, where the wait is eternal, the dangers are latent and misery is the norm. DIVERGENTES followed Nicaraguans who got stuck in this migratory funnel, from Honduras to the banks of the Bravo River.

BY Bryan Avelar

Guatemala City and Tapachula, México

After burning the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) flag that Nicaraguan government spies had left outside his door as a final warning that he must align himself with the regime or leave his community, German Sosa, a dark-haired, mustachioed, chubby man from the municipality of Chichigalpa, knew it was finally time to leave his country.

Threats from members of the Council of Citizen Power (CPC), a communal spying organization of the Ortega- Murillo regime, had been harassing Sosa for months. First they summoned him to meetings to discuss his “behavior” which he refused to attend, ignoring them bluntly. Then they began leaving him anonymous messages on pieces of paper in front of his house. And finally he frequently observed two plainclothes officers in a police patrol car staring at his door and taking pictures from across the street all day long. So when, in mid-December 2021, that FSLN flag appeared lying at the foot of his house, he knew it was a clear message. So he took the red and black Sandinista flag and set it on fire in front of his neighbors.

“The Cepesapos are here,” said Sosa to his wife, who was waiting inside their house. He then called a neighbor he trusted to offer him, at a bargain price, all the tools from his welding shop that he had managed to collect over the years. The next day he took a few things and the little money he had gathered and fled.

More than a year after abandoning everything, one morning in early June 2023, Sosa tells his story. He does so from a small patio, under the shade of a mango tree, in a suburban neighborhood in Tapachula, on Mexico’s southern border, a few blocks from the migrant shelter where he has been living as a refugee for the past six months. Sosa is one of hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans who, since 2018, have fled their country because of the Ortega-Murillo totalitarian dictatorship. And he is also one of the thousands of migrants whom the withholding policies pushed by the United States and implemented by the Mexican government keep trapped in this border city, living in shelters, plazas and streets in starvation conditions.

In the past five years, after the outbreak of the socio-political crisis in 2018, which devolved into a totalitarian dictatorship, Nicaragua went from not appearing in the ranking to being one of the main migrant expelling countries in Central America. The Nicaraguan exodus has become so severe that by January 2023 more than half a million citizens, that is, about 7.6% of the population, had left the country. That figure is equivalent to more than double the number of migrants who fled during the Nicaraguan civil war in the 1990s.

When the crisis exploded, many of those fleeing saw neighboring Costa Rica as a natural escape route. According to official data, as of mid-2023, more than 212,000 Nicaraguans had requested refuge in that country, accounting for more than 90% of all applications. However, the majority, more than 344,000, set their sights on the United States, according to a report by the Human Rights Collective Nicaragua Nunca +, presented in June of this year.

Many of the migrants fleeing Nicaragua are not necessarily major political opponents of the Ortega-Murillo regime. Most are fleeing as a result of the dictatorship that has sunk their country into poverty, repression and a hostile environment for those who do not support the government.

Four years before receiving that last threat that forced him to leave his country, 45-year-old Sosa had served the opposition Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC) guarding ballot boxes in the 2017 mayoral elections. Not that Sosa was a fervent activist for the collaborationist Sandinista party. At the time, Sosa believed that his sympathy with those political ideas would not bring him major consequences. But the spies of the Ortega regime did not forget that gesture and have since labeled him as an opponent in his community.

That is why, for years, members of the CPC or “Cepesapos”, as people not aligned with the regime in his neighborhood call them, tried to indoctrinate him. First by force and then with threats. They asked him to join the ruling party and to register to prove his loyalty. But Sosa refused to do so.

After the last threat, in December 2021, Sosa left his home for two months and went to take refuge in a community in the interior of Managua, the capital. There he met with a friend who was in a similar situation of harassment and together in February 2022, they left his country.

U.S. anti-immigrant policies force most who try to reach the U.S. to remain outside its borders while their refugee claims are processed, under threat that if they cross illegally they will be deported and will no longer be able to reapply for refugee status. Many of them stay in Mexico, forcing them to remain in inhumane conditions. Like Sosa, who now lives on food and shelter at the “Jesus the Good Shepherd” migrant shelter, and on what little he earns in a government program that gives “bonuses” to some migrants in exchange for community work.

Sosa has been working since February of this year, cleaning, tidying the bathrooms and serving the food prepared at the shelter where he lives. This job pays him about 5,000 Mexican pesos a month, about 300 U.S. dollars. That money, the Nicaraguan says, is mostly used to pay for the other two meals at a nearby diner and he manages to save a little in the hope of saving enough to move to a city in northern Mexico where he can earn more.

Tapachula, located in the south of the state of Chiapas, has become a trap-city for migrants trying to reach the United States since 2019. Historically, this city has been an obligatory passage for millions of Central Americans following the route to the north. But in recent years it has also become the epicenter of migratory waves arriving from South America, the Caribbean and even from other continents such as Africa, Asia and Oceania.

According to data from the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (COMAR), in 2022 alone, more than 118,000 migrants sought refuge there. But local activists believe that figure falls far short of reality, as most migrants seek to go unnoticed by authorities. Others, like Sosa, arrive in Tapachula and request a temporary visa for humanitarian reasons valid for one year.

But the immense demand that saturates the system and the bureaucracy that seems to be done on purpose have caused the process for both documents to usually take between three and ten months. During that time, migrants run out of money or are forced to take clandestine routes that expose them to the danger of being robbed, kidnapped, raped or killed along the way.

Although he already has his humanitarian visa after six months in Tapachula, Sosa has run out of money, as have the majority of migrants who remain stuck in this city. Local activists believe that, although the flow is constant, there are close to 40,000 migrants who remain here. This assertion becomes evident with just a brief tour. Any day, at any hour, Tapachula is full of migrants. They can be seen in the parks, in local businesses, filling the plazas and streets. This city, so to speak, is a cosmopolitan city at its most miserable version.

Although it is increasingly common for Nicaraguans fleeing north to leave the capital in private charter buses with tourists traveling to Guatemala City, Sosa and his traveling companion decided to sneak out of their country. “We left with a backpack each and ventured across the Guasaule border. I was just hoping the police wouldn’t stop us because if they stop you they take you to El Chipote prison, and they accuse you of being a traitor to the country,” says Sosa.

Sosa and his friend walked along dirt paths until they reached the Guasaule River, which serves as a natural border between Nicaragua and Honduras. But before they could cross the river a group of soldiers stopped them.

“They asked us for our documents. They asked us if we were fleeing the country and we told them we were not. From there they asked us for money and since I didn’t want to give them anything they broke my document,” says Sosa and shows his ID card torn to pieces and taped with transparent tape.

They both walked in the opposite direction, as if they were returning to Nicaragua, but slipped through some hills until they made it across the border. They crossed into Honduras and stayed for nine months in El Salvador, where Sosa had worked years earlier. During that time, the two Nicaraguans collected money and waited for six other compatriots who were also fleeing the regime for similar reasons. In December 2022 they resumed their route to the United States.

The entire migrant route is a risk for those who travel it. Migrants try to go unnoticed by the authorities and to do so they are forced to take dirt roads, shortcuts through mountains and paths where they risk being assaulted, kidnapped or even losing their lives. However, the first stretch that the Nicaraguan migrants travel, which goes from Honduras to Tapachula, in southern Mexico, is heavily marked by the presence of false transporters who swindle the migrants and by police who come out on the road and rob them in exchange for letting them pass.

Sosa recalls that he and his companion were robbed by Honduran police just a few kilometers after crossing the border into Nicaragua. “They stopped us and asked us for money. They told us they wanted $50, and from where were we going to give them that? But they took $25 from each of us, although I understand that someone coming from Nicaragua should have no problem getting through,” says Sosa. And he is right. Since 2006 there has been a Central American Free Mobility Agreement (CA-4) between the countries of Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala which, in theory, allows free inter-regional transit for six months between the citizens of the member countries without the need for a passport and with expedited migratory instruments.

The high flow of Nicaraguans passing through Guatemala City is so high that a Nicaraguan microcosm has formed around the bus station that arrives with tourists and migrants from Managua to Zone 1 of the Guatemalan capital. In its surroundings there are food stalls and souvenirs with the Nicaraguan coat of arms or the national flag. Some of these businesses are staffed by Nicaraguans who once wanted to get to the United States and were stranded there for various reasons. The Nicaraguans who get off the bus in that place, probably unknown to many, find a bit of nostalgia on their way.

Guatemala, however, is a hostile territory for migrants, including, of course, Nicaraguans. Once in the city, migrants who have made it there can take several routes. The most common, because it is the least expensive, is to board a bus at the station located in the Central de Mayoreo (CENMA), in Zone 12 of the capital.

One morning in early June, the journalist and photographer assigned to this report for DIVERGENTES arrived at the station with the intention of traveling to Tecún Umán, the border town on the Guatemalan side of the border with Suchiate on the Mexican side. When we arrived at the station, all the bus drivers assured us that they would take us to the border and some, thinking we were migrants, even swore that they could take us to Tapachula without papers. After charging us 150 quetzales, about $23, the bus left us stranded in Mazatenango where they then put us on another bus to drop us off in Retalhuleu, a town off the route to Tecún Umán. There they transferred us to another bus, charged us, again, 150 quetzales each, and dropped us off in Coatepeque, still 34 kilometers from Tecún Umán. There we boarded a small short-distance minibus that charged us 80 quetzales each, four times the normal cost, and finally dropped us off in Tecún Umán.

Almost all migrants who travel this route report that Guatemalan police stop the direct buses three to five times along the way and demand a fee from each migrant that can range from ten to fifty dollars.

Rodolfo, a Nicaraguan stranded in Tapachula, says that the group he was traveling with was robbed three times by the police. “The policeman just stops and says ‘well, you know how it is: twenty dollars each’ and passes by each seat. Anyone who doesn’t give them money is thrown out,” he says. Rodolfo has also been living for six months in the “Jesus the Good Shepherd” migrant shelter, the same place where Sosa lives.

Rodolfo first arrived in Tapachula in February 2022. He fled Nicaragua driven by poverty and lack of employment. After spending about six months living in the shelter and working to save a few dollars, he made his way to Tijuana, on the U.S. border. But Mexican authorities deported him to Honduras. Two months after returning to his country, and having lost all the money he had managed to scrape together during months of effort, he fled again. But this time he stayed in Tapachula. “I’m going to stay here as long as it takes,” he says.

Jhony Mayorga is a Nicaraguan lawyer with more than 20 years of experience in civil law who, until a couple of years ago, earned close to six thousand dollars a month litigating for renowned financial firms in Managua, the Nicaraguan capital. But since February 2023 he has been a waiter and manager of a taqueria in the northern zone of Tapachula. Sitting behind a small wooden bureau at the entrance of the taqueria, Jhony welcomes his customers with friendliness, brings the menu to the table, serves food or brings drinks to the customers.

“In Nicaragua if you want to work on a case that is against the government’s interests, forget it,” he says. Jhony says that since 2019, the regime has been blocking the exercise of his work as a lawyer. “There is a lot of repression in our country. They held a meeting in the central complex of the central courts in Managua and they began telling us which cases we could work on and on which cases we could not. They clearly told us that we could not defend cases of treason. Only certain lawyers assigned by the government could defend them,” he says.

Over time, Jhony began to be harassed, subpoenaed by the police and watched by plainclothes officers in front of his office. “Until one time, a policeman friend of mine told me that I had better leave because they were on to me,” he recalls.

Like Jhony, thousands who remain stranded in Tapachula opt to look for work. Most of the time these are informal jobs without any benefits. “I earn more or less well here. But it has cost me a lot to achieve it. I spent three months without a job, spending the money from everything I sold in Managua and asking my mother for it,” he explains.

In Tapachula it is common to see migrants working in restaurants, bars, hairdressers, clothing stores and in the market. The central plaza and Miguel Hidalgo park are full of Haitians with informal sales. Until before January of this year, when the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden extended the humanitarian permit known as “parole”, there were Nicaraguans in Tapachula in mass numbers. Now, after the United States threatened to be more drastic with those who do not follow the procedure and cross the border illegally, the number of Nicaraguans on the road north has noticeably decreased. But there are still many who dare to travel without papers living in conditions of hunger and poverty.

Sitting in a bar, Mariana has seen thousands of migrants pass through. In recent years she has seen the changing dynamics of migration and knows the dangers of the route north. The woman shows off her plunging neckline and crosses her legs every time she laughs. She is Nicaraguan, 37 years old, and arrived in Tapachula when she was just 12. She came here with her father from Managua after the family cheese business went bankrupt. Mariana sips her beer and speaks to me quietly with complicity in her tone. She tells me that she finds it strange that someone comes specifically asking for a Nicaraguan woman. She says that they are not very popular here. “They prefer them Cuban and Honduran, maybe because they like to dance,” she says and laughs again, crossing her legs.

Mariana has been a “fichera” in Tapachula for 12 years. Ficheras are a figure that exists in Mexico. They are female companions who drink with customers that buy them drinks that usually cost double or triple the normal price. As long as the company lasts, that is, as long as the client keeps buying them drinks, he can enjoy a conversation and also touch and enjoy the dances that the fichera performs.

Tapachula is a paradise for migrant smuggling, especially Central American women who, due to the conditions in which they live, are forced to work in prostitution or as ficheras. Luis Villagrán, an activist member of the Center for Human Dignification in Tapachula, estimates that there are 30,000 bars in this city and in almost all of them there are migrant ficheras working. There is no official record of this, as many of the bars operate informally.

Although there is a debate as to whether the work of “ficheras” is the exercise of women’s sexual freedom or a kind of trafficking, for local activists, the conditions under which this work is carried out tip the balance more towards the latter. “If a migrant woman spends months trapped here, starving and with nothing to feed her children, and is forced to work in a job where the main feature is to let herself be touched by any man, that is not sexual freedom,” says Villagrán.

The escort work of the ficheras often goes beyond that. After two beers, Mariana offers me that extra. She tells me that for 2,000 Mexican pesos, about a hundred U.S. dollars, she can “go out” with anyone who asks her for two or three hours. Although the price is negotiable, with what she earns she has been able to put her two daughters, ages 12 and 8, through school.

Her dream of reaching the United States has long since ended. Like thousands of migrants who live in this city, Mariana was caught in the trap called Tapachula. “Why am I going to risk it? I have my life here. It’s hard, but you get used to it,” she says.

By Franklin Villavicencio

Matamoros, México City

The first time that Francisco Javier Montalván, 63, set foot in Matamoros was very different from everything he has seen in recent months. His life has been marked by two exiles, and in both he has had to take the same route. The first was 37 years ago. The second began on December 18, 2022. This time, he says, he will not feel “homesick” again, that feeling that invaded him at the beginning of the nineties, when he believed that in Nicaragua a profound change had taken place that made him return to his country of origin, after having arrived in New York during the eighties, the decade of the fratricidal war.

Francisco has little memory of the first time he was in Matamoros, in 1986. He never spent a full day here. Almost immediately, a coyote crossed him to the other side. “Sure, there weren’t any fences around the river.” Neither were the more than 3,000 migrants waiting to cross into the United States. There were no drones flying over Rio Bravo every now and then, no immigration policies that force people to hang on for months to an email notifying them of an appointment to cross to the other side of the border.

In this second exile, Francisco has spent two months in Matamoros, a hot city, without trees, with an eternal layer of white dust that fills the streets, the vehicles and the people. With luxurious and, at the same time, empty buildings. With parking lots and buildings that resemble Texas, the neighboring city. Matamoros is a place that reminds us -as if it were an ironic wink- that we are so close to the United States and at the same time so far away. There are Texas license plates, more pickups than sedans, binational lives. It takes fifteen minutes to drive to Brownsville, the nearest U.S. city. Francisco, however, has been waiting for 60 days now.

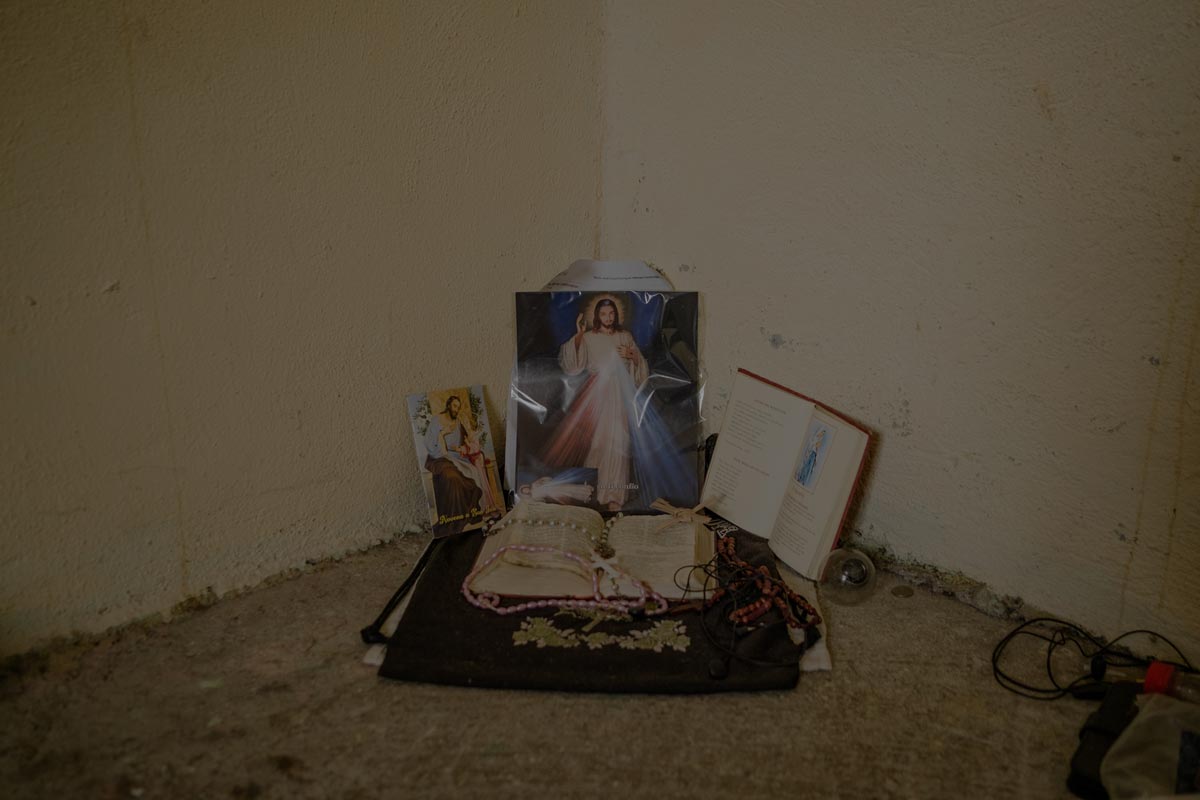

“I’ve lost my time here, lost weight, but I’m mentally prepared for all of this,” he says from a small room where he has slept for the last month with his nephew – a farmer who comes from a lineage of Contras who for fear asked not to be named – and the latter’s 23-year-old son. The three men sleep on crumpled cots. They have a fire stove, and nothing else. In one corner of the room they set up an improvised altar with Jesus and the Virgin Mary. They arrived there after some Cubans – who had paid for the month in advance – left it for them shortly after they were notified by email that they could go to the Matamoros border post to arrange their first interview with U.S. authorities.

Francisco and his family have been waiting for two months for the appointment through the CBP One application that the U.S. Government has enabled for migrants to register and apply for an eligibility interview at some of the immigration access points on the border with Mexico.

Matamoros is one of the points that hosts these migrants, who come mostly from Venezuela and Cuba. Nicaraguans are a minority. Finding them, at least after June 2023, is an odyssey. Partly because Joe Biden’s administration extended the humanitarian permit known as parole to nationals from Nicaragua, Cuba, Haiti and Venezuela. Also because the measures have been tightened for those who cross Mexico irregularly. The U.S. Embassy in Nicaragua disclosed that, as of June of this year, some 30,000 Nicaraguans have managed to enter U.S. ground thanks to humanitarian parole.

However, many like Francisco are stranded in Mexico. In his case, his departure from Nicaragua was related to his personal safety. He could not stay there any longer, as he worked as a teacher at the National Technological Institute, and the atmosphere within the institution was becoming unbearable. His superiors knew that he did not fully agree with the Ortega-Murillo regime. Although he had dedicated himself to training construction workers for 25 years of his life, that disagreement outweighed his professional experience.

Francisco used to give weekend lessons to young aspiring construction workers. However, before he left the country, he was only allowed to work one day a week. They imposed political indoctrination courses on him that were outside his area of expertise and he was constantly harassed at work. According to him, it was a way to suffocate him in his work. A tactic suffered by public officials of the regime who are often victims of the Sandinista leaders’ repressive mechanism.

So he decided to leave Nicaragua on December 18. The date was the same as his nephew’s departure, who is 47 years old. Francisco’s nephew is a peasant who was born in a village called Rio Blanco, in the department of Matagalpa, in the north of the country. He is proud of his past and calls himself a true opponent of Sandinismo. The nephew, whom we will call Marcos, comes from a family of counter-revolutionaries since the 1980s.

Marcos was raised in the countryside with an animosity towards everything red and black. Even anything that looked leftist, or communist, as he likes to say. The interior of Nicaragua is known to be a strong right-wing base, with a liberal – and even Somocista – tendency. Sandinismo is not well regarded there. The violence in that bloody decade made itself felt through extrajudicial executions without trial. Marcos‘ father, who served as a judge during the Somoza dictatorship, was assassinated when the Sandinistas took power. Violence and hatred only increased after that.

Years passed, and Marcos’ mother raised her two sons alone in Rio Blanco. Marcos watched his step brothers join the Contra, an armed group financed by the United States to overthrow the Sandinistas. He learned to arm and disarm rifles, to shoot, and to train in the mountains as a child. He was raised as a counter-revolutionary.

“We had about six properties more or less and they confiscated them all. The Sandinistas stole everything from us,” says Marcos with a singsong, country accent. Despite being family, he and Francisco don’t have much in common. Francisco is tanned, plump and short. Marcos is scrawny, with few teeth, his skin is yellowish, he has a thin mustache and his ideas are very different from those of his uncle. Francisco, at some point, believed in the Sandinistas. He grew up in the capital, studied and trained as a civil engineer. Marcos distrusts everyone, he feels that he is being followed in that lost and arid city, that there are Sandinistas everywhere looking for him. He lives with the paranoia he grew up with, one that, to a certain extent, is justifiable when you are born in the violent mountains of northern Nicaragua.

On a morning in early May, Gladys Cañas, 55, answered a call from journalists who contacted her asking if there were any Nicaraguans in the Matamoros migrant camp. Gladys stepped out of her office, located a block away from the camp, and shouted to the crowd of people who wait every day to talk to her: “Are there any Nicaraguans here?” Francisco raised his hand, and that’s how we got to him.

Gladys is a Mexican who has dedicated more than the last decade of her life to working with migrants. She is the founder and director of the organization Ayudándoles a Triunfar, located in a tiny office on the edge of the Matamoros border. Her job is to support the more than 3,000 people who remain in the migrant camp set up in a vacant lot on the banks of Rio Grande. It is a messy, chaotic and unhealthy camp. Inside, tents and shacks have been set up for the migrants to live in. The terrible living conditions have accelerated the presence of stomach diseases and other illnesses such as chicken pox. Inside, there is no life at all.

“It is really worrying. They arrive at this border and what they have to live is not life. All the people have tears in their eyes. Why? Because their time here has been extended,” says Gladys in her office. Outside, some 60 migrants are waiting to speak to her or one of the lawyers and assistants who work at the center. Everyone, Gladys says, has a story to tell. But there are too many people for such a small organization. Because of this, she has assigned a woman from Venezuela who seems to have been born for the job. Her voice and her face are serious, immutable. She is in charge of putting all the people in order, to prevent them from piling up and that, when Gladys leaves her office, they do not rush towards her. She gives out appointments and makes sure that migrants present their documents in order, in case they ask for legal advice. These are measures Gladys has had to take after the massive presence of people in the city.

The woman, with a sad and tired look, has linked her life to Matamoros, despite being from Tampico. She has been dedicated to the defense of migrants for 12 years, when in her hometown she watched Mexican migrants being deported from the United States. She never thought that some of those strong men dedicated to hard and tough jobs could break down and cry because of a deportation. Most of them arrived after years of living on U.S. ground, without much tying them to Mexico. All this made her want to delve into the causes of migration and work with these people.

“The camp is an alarm. It is a disorganized, dirty camp, with only 18 portable toilets for a population of more than 3,000 people. The conditions are abysmal at best,” Gladys says.

Her work is not only focused on legal advice, she also carries out clean-up campaigns in the camp and encourages the population to prioritize their health. It is common to see her in the perimeter on the banks of Rio Bravo, where there are hundreds of tents. When she arrives, she asks for volunteers to help her clean up the area. Almost immediately they are joined by about forty people who pick up the garbage. Gladys reminds them to stay out of the river, because it is polluted. But many ignore this call and swim in the river. When someone goes into the river, an audio message from the Border Patrol post on the other side of the river immediately plays, saying that the crossing is closed to irregular migration.

Marcos is at the camp that day, while his uncle stands in line outside a community center to get a meal. They occasionally visit this place even though they live on the outskirts of the city. Before, they had a tent inside, which they abandoned when some men started burning tents one night. “That’s when I told the old man that we were in danger here,” says Marcos. It is presumed that the fire was caused by the organized crime that operates in the area. Some 25 tents were affected.

The desperation to stay in this town is palpable in Marcos when he speaks. He wants to leave soon, like everyone else who lives here. In the camp, life goes on ordinarily. Men cut their hair and beards, women pat tortillas, young boys play with a deflated ball. But everything stops at 11 a.m., the time when the CBP One application usually notifies those who are selected for the appointment.

Having a cell phone here is everything. Thanks to this device, they can find out about their case. Marcos checks and still nothing has arrived. “Keep trying,” appears on the screen. He has been waiting for two months, in addition to the three months he has been stranded in Tapachula since his arrival in December.

Marcos left Nicaragua following the escalating repression against the Catholic Church by the Ortega and Murillo regime. The event that triggered his departure was the imprisonment of Bishop Rolando Alvarez on August 19, 2022. After that, the National Police persecuted all the people who collaborated with him. Marcos belonged to the group of the Archdiocese of Matagalpa and on certain occasions he was in charge of being Bishop Rolando Alvarez’s “bodyguard” when he went to rural communities. He did this as a religious service, as an act of faith and gratitude to the bishop.

Marcos‘ mother received a notice on December 15 requesting her son’s presence at the nearest police station. “And what was I going to wait for, that same day I prepared everything to leave. You must know what it means to be summoned to the police,” the man adds. And no, I don’t know because I have never been summoned, but in the last five years I have had to collect testimonies from political prisoners. A police summons means – in most cases – deprivation of liberty, without the possibility of a fair defense.

Among the family it was known that Marcos had been summoned, so his uncle Francisco, who was also living in suffocating working conditions, decided to leave with him. Marcos could not return to his farm in Rio Blanco, so he went to the house of other acquaintances in San Ramon, in the department of Matagalpa, where he met with his uncle. From there they headed north. When they reached the border with Honduras, they crossed through trails. “I know all that road,” he says.

They arrived in Tapachula, the trap city, in less than five days. There they spent two and a half months waiting for immigration authorities to grant them a visa for humanitarian reasons that would allow them to continue their route north. They both have been very careful to comply with all legal requirements to not have any problems when they arrive in the United States. However, the desperation and exhaustion is evident in both of them.

About four kilometers from the camp, in the center of Matamoros, Francisco waits for his daily meal. In line are not only migrants, but also homeless elderly adults and locals. The center, run by a Catholic congregation, delivers 80 meals a day, so people line up an hour in advance. That day, the meal consisted of two small hot dogs and a tomato salad. Francisco ate them on his way to the camp to meet his nephew. “One has to stay close to that area, because that’s where you find out about everything,” he remarks. It’s not enough for him to go home to bed. Information here is power, and the only vehicle for information is rumors.

The migrant camp is a border within a border town. Locals barely look at this stretch of land that holds an entire world. Most of the people who live there come from Venezuela, so Venezuelan flags are a common sight. Those who are lucky, live on the money sent by their relatives through remittances. Others go out to work or beg in the streets. A few establish businesses within the area, where they even ask for money to charge a cell phone.

Information here comes and goes in different forms. Sometimes it takes on the aspect of rumors and most of the time disinformation. “They say that on Tuesday they are going to open the doors and let us all in,” is the whisper of the week. Rumors stay afloat in part because they allow us to hold on to something, even if it is a statement far removed from reality.

At the camp we met another Nicaraguan who, like Francisco and his nephew, remains in a limbo, not knowing what his next steps will be. Juan Ruedas is 18 years old and has been here for almost a month. He was born in Chinandega, in western Nicaragua. There, Juan worked as a tricycle driver, a very popular means of transportation in certain cities. His salary of 200 córdobas a day (US$5.47 at the official exchange rate) was barely enough to live on. So last year he went to Costa Rica to work for a while. He arrived in Quepos, a city located on the Costa Rican Pacific coast, known for its tourist beaches. Since his arrival he started working as a construction worker, and that’s what he was doing when he met Jimmy Estrada, 25 years old.

Jimmy is a Colombian of Venezuelan origin who decided to leave his country to ” climb” to the United States. His plan was to work for a while in whatever came up along the way, earn some money and with the money finance his trip north. He arrived in Quepos and there he became friends with Juan. They both worked for seven months. They worked late night shifts, which earned them $40 a day. Despite this, they felt an attraction to the north that they could not explain. They believed they could do better.

So one day, after seven months of hard work, Jimmy announced to Juan that he was leaving for the United States. Juan did not hesitate for a moment. He drove through Chinandega, saying goodbye to his mother and older sister. “I got into some kind of depression. Depression because I didn’t want to leave, but at the same time I told myself that if I left I could help my family later on,” he says. Staying in Nicaragua, earning little more than five dollars a day, was not an option.

They started their journey and everything went smoothly until they reached Guatemala. At the Mexican border they boarded a raft that would take them across to Tapachula, but when they got off they were robbed by the same people who had helped them cross. They stole everything they had in their pockets, including a cell phone on which they had the CBP One application, with both of their registration for the appointment.

“Now we don’t know what to do, because we want to add a new account, but it won’t let us because there is already one with our names registered. And that one we can’t access because we lost access to the mail,” Jimmy relates. Both are concerned and represent a variable that reflects the vulnerability of technology in the migrants’ journey.

The afternoon is coming to an end in the camp and many go to their tents to wait for the next day to be notified that they have an appointment. Desperation is felt. “Do you know if they will open the doors on Tuesday?” asks one of the many migrants. Again the illusion, the clinging to something strongly emerges.

There are two shelters operating in Matamoros that have conditions for people coming from other countries in search of better opportunities. Both are run by the religious, with the support of civil society. In both, the number of Nicaraguans is minimal. Emiliana Herrera Flores, 35 years old, lives in “Casa Migrante San Juan Diego”, located half an hour away from the camp by car.

When one of her companions entered the women’s room of the shelter to tell her that she was wanted, she was frightened. Her first thought was that they were coming for her. An instinctive feeling for someone who comes from a country where any innocent person is guilty before the State. In Nicaragua, fear and terror have been imposed through persecution. It is not necessary to be a militant opponent to go to jail, it is enough with a neighbor reporting you and accusing you as an opponent of the Ortega-Murillo regime.

After realizing that the people looking for her were journalists, she calmed down and agreed to tell the story of her journey. Emiliana left three children in Nicaragua, ages 17, 14 and 7. She left the country because of the economic crisis that is affecting the finances of Nicaraguan families. The cost of the basic food basket was increasing and the salary of 12,000 córdobas (about 327 dollars) that she earned as a waitress and cashier in a restaurant in the capital was not enough to support her and her children. Calculations up to February 2023 put the basket at 19,000 córdobas (US$519 at the official exchange rate).

So one day, after meeting a group of Venezuelans that a friend of hers asked her to host while they were passing through Nicaragua, she decided to go with them to the United States. “I did it for my children. Before I left I talked to them and they understood the situation,” she says. However, the youngest of them is the one who tells her the most that he misses her. “I made you a present right now for Mother’s Day, look at it,” he sent her on May 30 through a WhatsApp audio. On that day mothers are commemorated in Nicaragua.

Emiliana left Managua with 12 other people, all Venezuelans. She did it alongside them to have company and not feel so lonely on the journey. In fact, she stays in the shelter with one of them, with whom she became close friends.

The journey to Guatemala was relatively calm. However, after crossing the raft she was swindled by coyotes who stole 600 Mexican pesos (about $35 at the official exchange rate) from her. It was a tense moment for her, as they asked for at least that amount, otherwise they would not let her go. One of them grabbed her arm, preventing her from fleeing. She had previously negotiated a much lower amount, but once she crossed, they raised the price.

Finally, a bus driver who was waiting for her in Tapachula to continue her journey came to her rescue. Without him, she says, she does not know where she would be. Every time migrants approach Mexican territory they suffer various types of violence. They enter a territory that sees them as merchandise. Like a chest to take money from.

After crossing Mexico City by bus, the checkpoints are constant and dangerous. The danger is embodied by the authorities and officials themselves, some of whom are often linked to organized crime. Emiliana always tried to pretend to be asleep, to cover her eyes with a hat and pretend to be resting, although her senses were very attentive to everything going on around her. “In one of those they took us all down, they wanted to ask us for money. I only had 150 pesos (about 9 dollars), which was my lunch for that day”, she remarks.

Emiliana has heard that on certain occasions in Tapachula, officers that detain people who don’t give them money, tear up their immigration forms, which migrants use to move around Mexico. For that reason, she decided to laminate it. When she arrived in Matamoros, she did not know where to go. After arriving at the bus station, a woman who saw her alone in the terminal and sensed that she was a migrant recommended the shelter where, at the time of publication of this report, she was still waiting for an appointment. Time in Matamoros has become eternal.

Francisco’s desperation has been such in the last few days, that on the morning of the last day we were with him he decided to get as close as he could to the immigration post that divides Matamoros from Brownsville. “I’m looking at options,” he says. Being here is even forbidden to a certain extent, since it is a federal zone. Crossing and going unnoticed is an unthinkable task. Surveillance is extremely high. On this side there are Mexican National Guard agents, and on the other side there are many Border Patrol agents. Deep down, Francisco has come here to feel what it is like to be so, so close to his goal.

The anxiety will not last long. Gladys confirmed that the next day he will be able to cross without the appointment, because there is a deal between the U.S. authorities, Mexican authorities and civil society organizations to prioritize ten cases a day so that they can present themselves at the immigration post. Those who are prioritized are vulnerable people who actually apply and have a case for asylum. Francisco and his nephew carry with them evidence that proves that their departure from Nicaragua was due to political persecution.

Francisco, his nephew and his nephew’s son crossed on Tuesday, May 30, 2023, after a six-month journey through Mexico. “Already passed the Mexico check,” was one of his last messages. “Already in Orlando,” was the last. After that, none arrived. His nephew also stopped receiving messages:

—Already in Orlando, was the last thing he reported.

—A new life.

—That’s right.

Emiliana also managed to cross into the United States two months after Francisco. She did it just like them, with help from the shelter where she stayed at. On an afternoon in mid-July she wrote from a number with a New York code:

— Already on the other side. New York is very nice, but even nicer is the fact that I will be able to send money to my family.

This report was made between June and August 2023 in Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico.

Texts written by Bryan Avelar and Franklin Villavicencio.

Videos and photographs by Fred Ramos.

Editing by Wilfredo Miranda Aburto.

Illustrations by A.Z.F.

Design by Ricardo Arce.

Logistics by Carlos Herrera.

Coordination by Néstor Arce.