“There’s gold everywhere around here,” says a police officer after stopping us and making sure we’re not illegal miners. “This is the famous Crucitas area, and a lot of people cross over from the other side to dig up dirt.”

That “other side” is Nicaragua, less than four kilometers away from where we ran into the police operation—just minutes after speaking with Omar Guillén at the La Venada dock, which is really more of a muddy pit on the Costa Rican bank of the San Juan River, where narrow paddle canoes dock carrying the miners the police are searching for in the dense forest.

“I’ve got a few little jobs on this side. One of them is taking people who cross over—on that red motorcycle over there, which has a permit,” says Omar, pointing to his left, where several other motorcycles with Costa Rican plates are parked. “Up there, into the mountains. A lot of guys come through, but if the law shows up, everyone takes off. Not me—I’ve got a permit to be here.”

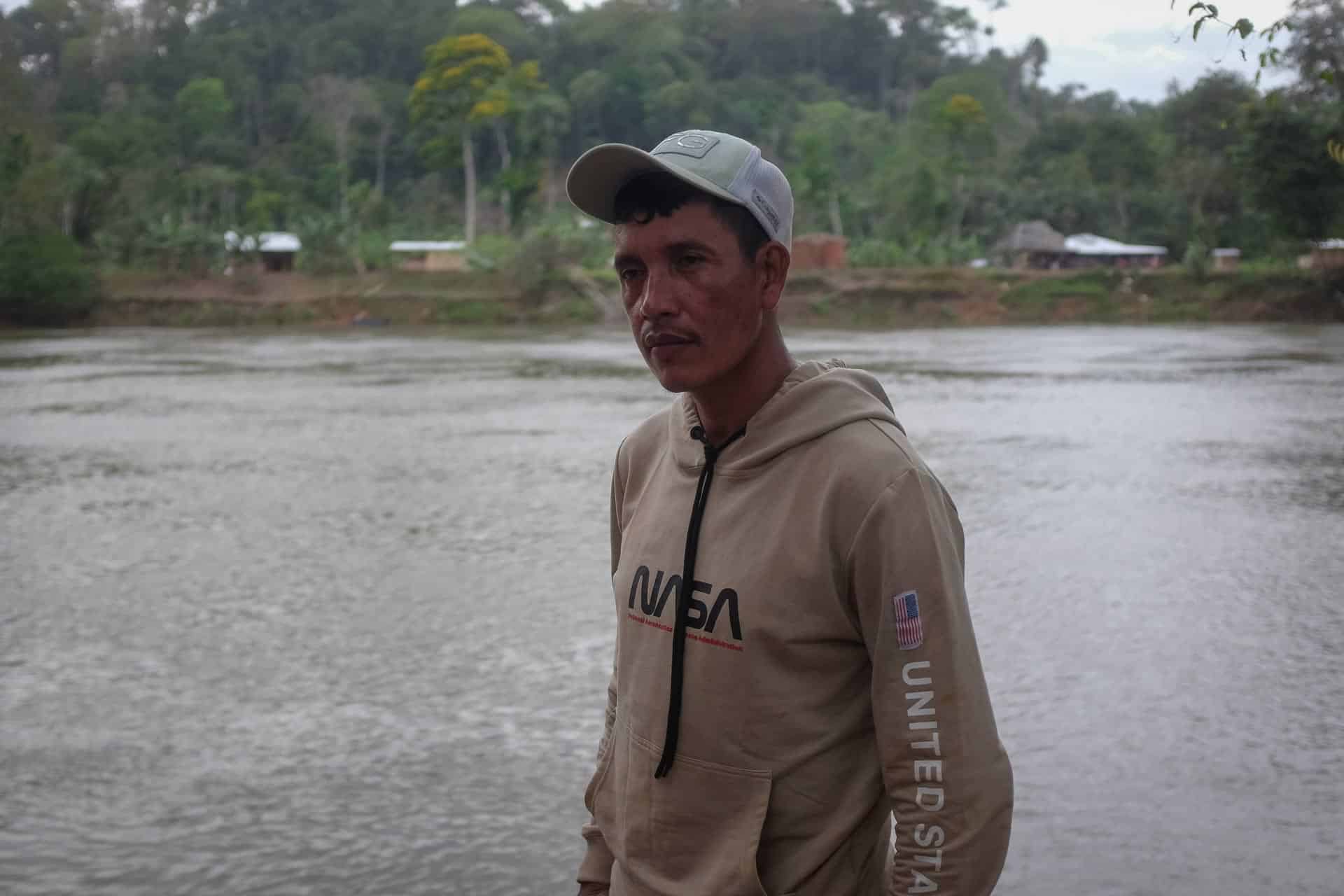

Omar is in his mid-thirties. He’s skinny, and his slightly crooked nose gives him the look of a boxer who retired early. He’s new to this border zone—he arrived just fifteen days ago, in late April 2025—but he’s already settled in. Even though “business” is going well, from the dock he gazes anxiously—his worry written all over his face—at the house with solar panels he just bought across the river, on the Nicaraguan bank, in his home country. A few months ago, his wife died by suicide in Rosita, a mining town in Nicaragua’s North Caribbean Coast where they used to live. Omar doesn’t go into detail about the reasons behind her death, but he does say he came over to this side “to erase the trauma for the girls.”

“You get me?” he asks. “Life’s harder over there—here it’s easier, and the girls can forget.”

He bought the small wooden house and the plot of land for 200,000 córdobas—about $5,464 at Nicaragua’s official exchange rate. For the past three years, word has been spreading among artisanal miners in the Triángulo Minero—where Rosita is located—about the chance to acquire “affordable” land near the San Juan River, specifically within the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge (RVSSJ). This refuge borders the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve and the Rama-Kriol Indigenous Territory. It’s an area of immense environmental importance, home to primary tropical forests, wetlands, rivers, and mangroves. It’s a key corridor for maintaining biological connectivity between Mesoamerica and South America.

Because of its significance, this vast forest in southeastern Nicaragua—which connects directly with Costa Rica—is protected under national law, international conservation agreements backed by UNESCO, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. In other words: selling land here—whether in front of the La Venada dock or anywhere within the 3,069 square kilometers that make up these three reserves—is strictly prohibited. But Omar bought without issue, no big fuss—just gathered the money and handed it over to Eliecer Hernández, the landowner who allegedly sold it to him.

Omar plays dumb about the fact that buying a house and land in this part of Nicaraguan territory—which, on the Costa Rican side, is known as the Chorreras community—is an illegal act.

“So how did you legalize the purchase of the property?” I ask him cautiously. It’s a sensitive topic among people like him—known as colonos by the Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities who have been displaced not only from this binational forest, but also from other reserves like Bosawas and the Miskito and Mayangna territories in Nicaragua.

As a journalist, I’ve spent years investigating and documenting these illegal land deals and the violence surrounding them: the web of deeds and public notaries who operate under the protection of a regime that’s plundering the country. A regime that, just twelve days before this trip to the San Juan River—on the Costa Rican side—passed the so-called “Law on Environmental Conservation Areas and Sustainable Development.” This law prioritizes “economic development” over environmental conservation and the rights of Indigenous communities, including the right to consultation. Colonization is no longer just tolerated—it’s now backed by law.

“There’s no deed, but there is a certificate… I’m not the only one here—there are about a hundred houses in La Venada. Not as many as down that way,” Omar tells me, gesturing north across the San Juan River, that wide, shallow current murky with sediment, the natural border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica—a vital waterway for both countries and a long-standing source of conflict… even of national identity, between Managua and San José. “Right now there’s a project to build a school in La Venada, but you know how those projects go. They take forever.”

Omar has joined, as a colono, one of the most destructive conflicts facing Nicaragua’s forests and its Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples: the unchecked invasion of communal lands and protected areas. Although it’s a long-standing issue—just like every Nicaraguan government’s view of the vast Caribbean region as a prize to be exploited—the situation has worsened dramatically over the past fifteen years under the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo.Whether by omission or—more often—through active complicity, Sandinista officials have trafficked land with total impunity. Landowners like Eliecer Hernández, who sold to Omar, have ties to the ruling party and acquire large swaths of territory only to resell them to these colonos. It’s the only way to operate networks of fraudulent public deeds or “certificates” without any state interference. Many of the buyers—colonos like Omar—even end up declaring themselves Sandinistas to ensure they can keep the land. The clearest sign of this are the red-and-black flags we begin to see flying in the settlements along the banks of the San Juan River.

The profile of these colonos can be broken down into four main groups: cattle ranchers, farmers, loggers, and miners. All of them are extractive industries that destroy the forest and displace entire Indigenous communities. This colonization process has left at least 70 Indigenous people dead over the past 15 years. And since 2018—when an illegal farmer sparked the massive wildfire that scorched 6,788 hectares of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, and the government’s negligent response ignited the public uprising against the Sandinista regime—the invasion has become total.

The colonos haven’t just occupied the core of the reserve—they’ve pushed through it entirely, settling in force along the banks of the San Juan River over the past three years. There, only the border has managed to stop the construction of settlements on the Costa Rican side, but not the expansion of activities like mining, cattle ranching, deforestation, and wildlife trafficking. The invasion of Indio Maíz has now crossed the river, becoming a binational problem—one that, for now, few in Costa Rica seem to notice.

The 2018 Indio Maíz wildfire was the prelude to the public outrage against the Ortega-Murillo regime that eventually led to the April uprising. Since then, organizations that defend Indigenous peoples have documented 161 violent attacks on communities. In addition to killings, these include kidnappings, sexual assaults against women, and permanent injuries caused by firearms.

The fact that the invasion has reached the San Juan border, Omar says, is due to the “saturation” of Nicaragua’s protected reserves. Indio Maíz has been carved up into parcels, and the forest along the border is now the area with the most “available” land to set up a “small farm at a good price.”

On previous trips into Indio Maíz, DIVERGENTES confirmed the existence of entire settlements built by colonos, complete with corner stores and bars. Or if you don’t believe us, just open TikTok and type in “Indio Maíz”—you’ll find dozens of posts showing intense mining activity, newly built villages, and even footage of nightlife. For example, at the “Selva Negra” nightclub, in the area known as “Managüita,” cumbias by Grupo Kiri de Cristian Morales blast through the speakers, Toña beers flow freely, and sex workers offer their services. Some miners even find cocaine or crack at the club before heading, high and hyped up, into the tunnels—tunnels that have, more than once, collapsed and buried them alive.

@treminio333 ♬ La Cumbia Kiri – Grupo Kiri de Cristian Morales

And I return to the data because it quantifies the damage to protected areas. Since 2015, approximately 60% of Mayangna and Miskito territory has been invaded by colonos, leading to the displacement of more than 3,000 Indigenous people—even into Costa Rica, where hundreds now live in precarious conditions in cities like San José.

The core zone of the Bosawas Reserve has already lost 12.8% of its forest cover, equivalent to 97,081 hectares. In the case of Indio Maíz, the loss reaches 38.7%, and in the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge—where we spoke with Omar—the degradation stands at 32%.

In the past two decades, according to Global Forest Watch, Nicaragua has lost 22% of its forests and, according to the United Nations, has the highest deforestation rate in Central America. In its latest update, Nicaragua ranks among the ten countries with the highest levels of deforestation. Seventy-eight percent of that loss occurred in the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve, with 74,000 hectares affected.

The data makes more sense when you set foot in these territories. Where there was once dense forest, now there are century-old trees snapped by chainsaws. Cows graze in the green heart of the jungle. Corn, root vegetables, and banana plants have replaced the corridors once used by jaguars and tapirs. Gaping tunnels open toward the sky, exposing the red, acidic soil—soil that holds gold “everywhere” and fewer and fewer mountain almond trees for green macaws to nest in.

When Amaru Ruiz, a biologist and director of Fundación del Río, launches his drone from the Costa Rican side and the device crosses over the San Juan River, the phone screen lights up with holes everywhere: open wounds in an invaded jungle, bleeding earthy mud, washed out by the rains… Hundreds of illegal properties spread like the footprints of a giant determined to dry up the forest and its mountains. From the Costa Rican riverbank, Omar watches them with a heavy, deep-set anxiety. To him, that devastated landscape is also an infinite opportunity—the way he’s found to support his daughters, now motherless.

***

Crossing the San Juan River on rowboats costs 30 pesos. Less than a dollar. The current is steady but gentle in the community of Chorreras. In under eight minutes, the miners cross from one country to another. Omar Guillén chose this place because he, too, was once a miner in Rosita. He understands the ins and outs of digging through the earth to find gold and knew this was a high-demand area because it connects to Crucitas—the mining district that marked a turning point in Costa Rica’s gold industry.

In 2008, the administration of President Óscar Arias granted a 50-hectare forest concession to a Canadian multinational to begin construction of an open-pit mine. But in 2010, following fierce opposition from environmentalists, the Administrative Court annulled it. A year later, the Costa Rican parliament passed a law banning open-pit metal mining nationwide. Since then, the area has been designated a priority conservation zone, especially as it forms part of the San Juan–La Selva Biological Corridor. Gold prospecting is strictly prohibited under any circumstances.

But north of Costa Rica—from the waters of the San Juan River, which belong to Nicaragua—conservation is nonexistent. The Ortega-Murillo regime has allowed environmental invasion and looting on such a scale that artisanal miners (known in Nicaragua as güiriseros) now cross the river to seek gold in Crucitas, where the competition is fierce.

“I take over a dozen guys across every day. There and back,” Omar says.

The strong Nicaraguan presence in this border area of San Carlos canton is evident even in the trash along the dirt road: discarded Toña beer cans.

“You’ll mostly find Nicas around here,” the man adds, swatting away a fly that keeps landing on his crooked nose.

Crucitas has become hugely popular among güiriseros from Nicaragua because of its untapped gold reserves. In La Venada, the hamlet where Omar lives, it’s starting to look like a small town. The miners claim they’re building a school and even a church. From this Costa Rican side—where we’ve come to safeguard our freedom, since in our country the Ortega-Murillo regime imprisons journalists, especially those of us declared “traitors to the homeland” and “fugitives from justice”—you can see wooden houses under construction and columns of smoke rising from the homes already built.

Las Chorreras lies just south of the border shared by Nicaragua and Costa Rica. But it’s not the only section being overrun along the banks of the San Juan: nearly the entire border corridor is dotted with settlements—from here through Boca de San Carlos, Sarapiquí, and all the way to the river’s delta, where the Ortega-Murillo regime continues a stubborn dredging operation with no environmental impact assessments.

On this journey, just beginning, we’ll eventually reach the Delta, where the San Juan widens even more. Although it drains into San Juan del Norte, most of the water flows into the Colorado River, at the confluence where the dredger’s engine rumbles like a rusty snore carried by the wind from the Nicaraguan canal into the Delta. That final stretch is also packed with invaders, who shamelessly settle next to Nicaraguan Army and Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Marena) outposts. Both institutions share facilities and, in theory, should prevent such occupations.

But they don’t.

A study by Fundación del Río has documented, since mid-2022, “an alarming invasion and illegal occupation of land” in Nicaragua, including “the clandestine sale of plots within this protected area.”

Amaru Ruiz, a biologist now exiled and stripped of his nationality, knows this southeastern Nicaraguan forest like few others. Since childhood, his father—the late environmentalist Antonio José Ruiz—took him on expeditions with Fundación del Río. Later, they moved to San Carlos, where Amaru learned to embrace the San Juan River as his own. He knows the area on both sides of the border intimately. He doesn’t need GPS to get around—except to map out the places already occupied by settlers. Over the past three years, he’s dedicated his work to documenting what his organization calls “the new front of reserve invasion via the San Juan Riverbank.”

The report from Fundación del Río identifies 1,587 illegal structures inside the San Juan River Wildlife Refuge (RVS-RSJ), specifically in the strip between the mouth of the Bartola River and the Colorado River. These are settlements formed over the last 36 months—a rapid 49% increase in new villages. “Three years ago, they didn’t exist,” repeat the dozen Costa Rican locals interviewed by DIVERGENTES. These occupations are located in restricted management zones where, by law, the establishment of residences is expressly forbidden.

“Las Chorreras is a mining town that emerged in a different context. However, with this invasion, people now enter through Las Cruces, into the Indio Maíz Reserve, and then exit into this area on the Costa Rican side,”explains environmentalist Amaru Ruiz, standing atop a hill overlooking a plot of land that until recently was still forested.

“These güiriseros find a supply chain in Costa Rica—from basic grains to mining supplies—because the terrain here is much more accessible. In Crucitas, the mining population finds farms that allow them to extract soil. We’re investigating an entire trafficking network of mercury and cyanide.

That’s why,” Ruiz insists, “we are witnessing a full-scale invasion of the left bank of the San Juan River.”

It’s not that Costa Rica’s Fuerza Pública (National Police) is unaware of the incursions by Nicaraguan güiriseros. In fact, they claim to patrol the farms and trails of Crucitas “24 hours a day, seven days a week.” Nearly every week, they report seizures of fuel, gold extraction drums (tómbolas), generators, shovels, pickaxes, and other tools. In just the first three weeks of April, they captured 50 miners.

“So far in April, we’ve dismantled ten mining processing centers operating with ten drums. We prevented ten sacks of cyanide, six jugs of muriatic acid, and 500 grams of mercury from contaminating the waters and soils of the northern border,” says Freddy Guillén, Director of Operations for the Fuerza Pública.

At the central government level, however, Rodrigo Chaves’ administration is not addressing this situation through an environmental or territorial sovereignty lens. On the contrary, it has hinted at the possibility of reactivating open-pit mining, specifically in Crucitas.

Pilar Cisneros, ruling-party congresswoman and Chaves’ main political ally, stated in early May 2025 that Nicaraguans are “taking Costa Rican gold.” But her focus was not environmental—it was purely economic:

“We Costa Ricans are giving away gold worth $4,000 an ounce. So Nicaragua can boost its exports. They’re already exporting more than $2 billion a year. It’s our gold, and they’re leaving us with all the contamination,”Cisneros declared.

She said nothing about Costa Rica’s 2011 ban on open-pit metal mining, nor about the fragility of the transboundary biological corridor.

On the ground, meanwhile, the Fuerza Pública does what it can to contain illegal extraction. They shut down excavation sites, map them with GPS, and patrol with drone support. But stopping this invasion is far beyond their capacity. In such a vast, dense jungle region, the güiriseros slip through in countless ways. If they’re not arrested and manage to return to Nicaragua, they simply cross the San Juan again days later to dig in another part of Crucitas.

It’s literally a cat-and-mouse game—with hundreds of mice.

Twenty-one kilometers downstream on the San Juan, “Sergio” knows that game well. He’s Costa Rican and, due to what he’s about to admit, asks not to have his real name published.

“I have a hole there with some guys,” he says.

“Nicaraguans?”

“Yeah, they’re all Nicaraguans. From Bonanza, Siuna, Rosita…”

We moved on. Crucitas is behind us now. We’re further north along the San Juan River, in the area known as Boca de San Carlos: a relatively populated region on the Costa Rican side, home to schools, health clinics, and farms, all lined by the border road ordered by former president Laura Chinchilla in 2011 in response to the Nicaraguan invasion of Isla Calero (as it’s known in Costa Rica) in October 2010.

That high-profile diplomatic conflict ultimately resulted, for Costa Ricans, in a 160-kilometer-long road project riddled with irregularities. The road was never completed. Today, some stretches are covered with river stones that look like baby dinosaur eggs; in others, the rain has left behind puddles turned into small lagoons, muddy pits, or crumbling remnants of asphalt eroded away by time.

Life in Boca de San Carlos is lively. That’s where we find Sergio: an older, chatty man, a local who has witnessed decades of gold activity—but never anything like this. Just across the river, on the Nicaraguan bank, lies a mining town called Veracruz, founded just over three years ago. From this side, you can make out a long line of zinc rooftops, blurred by the thunderous downpour that’s falling this afternoon, casting a thin veil of mist over the current.

“How big is Veracruz?” I ask.

“Ufff, man, you get there and you can’t even walk. Feels like a market every day. There are like twenty mines. And listen, tunnels go a thousand meters down.”

“Is that better than Crucitas?”

“Way better!”

“And who do they sell the gold to?”

“The buyers come right there. They’re Nicaraguans.”

“Does any of it go to the Costa Rican side?”

“No. Gold’s worth more over there. A gram goes for twenty, twenty-two thousand colones. But listen, those people know exactly what they’re doing. Let’s say you’re the buyer—a young guy, you show up with two others, all carrying huge black bags stuffed with wads of cash. All in cash. If you want colones, they’ll give you ten million in colones. Or córdobas. Whatever you want,” Sergio says, before admitting that his own “hole” is on his own farm, on the Costa Rican side. He makes an informal deal with the güiriseros: if they make 100,000 colones, they owe him 20,000.

“They come with the money. They say, ‘Put the gold here.’ They’ve got blowtorches in their backpacks and start heating it up, purifying it. They melt it down… then they weigh it until it’s the right amount. Right there, in front of you, they pay you. And no one steals—because if you steal, they’ll kill you,” Sergio adds, suddenly dropping his light-hearted tone. Now he’s dead serious.

“So they’ll just kill you?”

“Yeah. That’s what happens on the other side. Nobody steals.”

“No police?”

“No.”

“What about the Nicaraguan Army?”

“Nope. They only show up when someone’s dead—and they don’t even investigate. ‘He messed up, there was a problem, he got killed,’ and that’s that.”

“But there’s a military outpost near Veracruz,” I point out.

“Ha! They don’t get involved. Not long ago, they killed a guy from the country where Maduro’s from… uh…”

“Venezuela?”

“Yeah, that’s it. Venezuela. May God rest his soul. He tried to act slick…”

“And what happened after?”

“Nothing. Everything keeps moving. With money, everything moves—land, weapons.”

“I imagine there are lots of weapons on the Nicaraguan side.”

“Yeah, but actually they come to get them over here, on the Costa Rican side. Over there it’s really hard to get guns. There’s no ammo in Nicaragua.”

The impunity Sergio describes in the invaded reserves on the Nicaraguan side is reflected in the frequency of crimes committed in those areas. In December 2024, for instance, güirisero Ariel López Pérez murdered his one-year-old stepdaughter in Indio Maíz, specifically in the sector known as “Managüita,” where the Selva Negra nightclub operates and where people drink Toñas to the rhythm of Grupo Kiri cumbias. The crime only came to light 14 days later, when the child’s mother told other miners.

López Pérez was detained by fellow güiriseros, who held him until National Police officers arrived. On December 20, Sandinista state-run media reported his official arrest. The man had strangled the girl, wrapped her in black plastic, and thrown her into a pit—one of those incredibly deep ones Sergio had mentioned.

In October 2024, another brutal crime occurred. Manuel de Jesús Cano and Yahaira Sevilla were shot and dismembered just one month after paying 120,000 córdobas for 100 acres of land in Indio Maíz to mine gold.

“See why I’d rather not give you my full name? People can find you easily here—and they’ll kill you, man,” Sergio says apologetically.

A new celebration on July 19th

The downpour has just stopped, but that’s no guarantee it won’t return. In this humid tropical forest, afternoons are always rainy. Each day brings small monsoons: it rains furiously for half an hour, then the clouds part and the sky clears, while the sun bounces off the wide waters of the San Juan River as if it weren’t a river at all, but the moat of a castle—one of those imagined by the band Malpaís, with palm fronds for walls. Birds emerge from the treetops, shake off the droplets, and take flight. José María Flores Arróliga—”Call me Chema,” he says—is already used to these sudden shifts in weather. A year ago, he embarked on this journey in his sea panga: he moved to the San Juan River, to the community of Machado, near the town of Nuevo Amanecer, one of the largest illegal settlements in the protected reserve.

He had lived for twenty years in Bluefields, on Nicaragua’s southern Caribbean coast. He had managed to buy a panga—a fiberglass boat sturdy enough to handle the open sea—and made a living from fishing. But he heard that along the San Juan there was land available for farming, a trade he also knew well. He’s originally from Nueva Guinea, a largely agricultural municipality, and he had worked on his parents’ farm since childhood. What he inherited, he says, was just a small plot, as the property was divided among his siblings. And now, with “three sons” of his own, he needed to secure something for their future.

“I grabbed my panga and came by sea from Bluefields to here.”

“How long did that kind of trip take you?” I ask.

“It was two long days. By sea. I came in through San Juan del Norte.”

One of the first things he did upon arriving was go straight to San Carlos, the departmental capital of Río San Juan, to register the panga with the General Directorate of Aquatic Transport (DGTA) under the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure (MTI). He was assigned registration number 3638. PTO S/Carlos. Transporte Flores. Chema had no issue when he gave his new address: the community of Machado, right in the heart of the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge. A place where, by law, building is prohibited.

“I’m taking a chance with 100 acres. I bought them for forty thousand pesos. It’s not much,” says Chema. In other words, the price of that piece of land amounts to 300 córdobas per acre, about 10.87 dollars each. He hopes that soon the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo will deliver the property titles they have promised to the 200 families living in Machado.

The community is named after the last name of the landowner who sold the estate to Chema—a man who, he says, is also connected to the Sandinista Front. But like other settlers, he prefers not to give us the landowner’s phone number.

—As a precaution —he says.

A report by Fundación del Río denounces that the early dynamics of the invasion, according to testimonies from the settlers themselves, were promoted by Valerio López, a former official of the El Castillo municipal government, and Gladys Sánchez Mondragón, the current Sandinista political secretary in the same municipality.

The second dynamic of invasion identified took place through a supposed “Sanitation and Protection Project for the Indio Maíz Reserve.” Fundación del Río accessed various documents containing “endorsements” signed by Jorge Ariel Omier Ruiz, current president of the Rama and Kriol Territorial Government (GTRK), an ally and militant of the ruling party. Also involved were Julio Ruiz Daniels and Leonel Sabala Tinoco, both lawyers from the municipality of Bluefields, along with the beneficiaries Francisco Sevilla Gutiérrez, Julio César Tenorio, José Adán Jarquín Gutiérrez, and Germán Abelino Velásquez. The endorsement stipulates a payment of 3,000,000 córdobas for 50% of the sanitation project in the area known as Bartola.

In that regard, Machado is ahead. According to Chema, the National Institute for Development Information (INIDE) has already come to conduct a census of the population. A school and a health center are being built, while settlers work on obtaining permits from the Ministries of Health and Education.

—Well, there are several people selling land here. I bought mine from someone local, the founder of the community. You buy, and that’s how deals are made.

—And do you have any documents?

—No, there are no deeds yet. But government people came and did a census. They took measurements and asked who was responsible for each piece of land. Supposedly, based on that census, they’ll give us titles later.

—Do you pay taxes?

—Not yet. When the title comes, then we’ll pay. For now, we’re more relaxed. We pay a little something to the San Carlos municipality, but that’s it.

—And did the municipality give you a receipt?

—No, nothing.

—Do you have public services?

—There’s no power grid. We use solar panels. For water, we bring it from the mountains, from the streams. Some have pumps.

Chema explains that from the San Juan River inland, there are mining operations, though the number is lower compared to upriver, where we came from. In Nuevo Amanecer and Machado, cattle ranching and farming prevail.

—I don’t have cattle because I’m just getting started. But farther in, near the streams, there’s plenty. It’s all cleared out. I cut down some trees, but near the streams I left some standing, so it looks nice, because now that land is mine. I’m planting plantains, cassava, and watermelon —says Chema, trying to sell us some enormous, oval-shaped watermelons that look more like missile warheads. They’re the last ones left in his boat, after selling the rest upriver to other communities.

The settlers agree that on the plots they’ve acquired —illegally— they grow a variety of crops on small plots of land. “There’s mention of simultaneous cultivation of plantains, cassava, and other root vegetables, following a logic of ‘getting a little of everything from each acre of land,’” the Fundación del Río report notes. “This suggests a subsistence model aiming to establish itself as a permanent productive activity.”

Properties closer to the San Juan River are more valuable and in higher demand due to their accessibility and fertile soil, which has incentivized intensive land occupation for agricultural use. The same applies to cattle ranching along the streams that feed into the San Juan River, where proximity to water is key for the livestock. This activity necessarily involves clearing virgin forest and intensive deforestation, which not only impacts forest cover but also leaves soil vulnerable to erosion. Sediments then get washed into the river.

Chema keeps insisting we buy his watermelons because they’re the last ones, and he’s offering them cheap: a thousand colones each. He sends one of his sons to fetch the remaining ones from the boat to show them off and says they’re saving up because, in two months, Machado will celebrate its second patron saint festivities in its very recent history. The first one took place when he had just arrived. It was the symbolic founding of Machado as a riverside village along the San Juan.

The bosses— says Chema, without naming names— brought a young bull and slaughtered it.

There was a feast, cumbia music, beer, and liquor. It all happened on July 19, 2024—the day they chose to mark Machado’s festival. A big bash.

—And why did you celebrate on July 19? Which saint was it for? —I ask with feigned innocence, because every Nicaraguan knows that date marks the peak of Sandinismo: the anniversary of the Sandinista revolution.

—Well, because that was the day to do it… The government is kind of giving us a chance to work. So there are two things: you’re either with the government or against it. If you’re against it, then you get nothing. I’m with the government, no reason to hide it. So we chose that day.

—So it was a real celebration.

—Everyone ate.

***

Marvin José Montoya isn’t interested in patron saint festivals. He has another, more urgent concern: enrolling one of his children in the school in Boca San Carlos —that is, in the Costa Rican education system. The boy is Nicaraguan and lives on the other side, in the settler community of Santa Fe, within the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge. Only the deafening downpour forced him to pause his trip to the school; as he waits out the rain, he drinks a Toña beer in a small roadside soda with a zinc roof. He’s also a farmer, originally from the Nueva Guinea area.

He obtained a 100-acre plot and says he already has deeds for it, for which he paid 2,000 córdobas to the San Carlos municipality, though he’s still waiting for the official land title. He didn’t receive any receipt for the payment, and when asked what guarantees he has, he just shrugs.

—My wife wants us to get the little one into school, but since we don’t have a school in the community yet, we have to cross the river.

—And are they letting you enroll him even though the child doesn’t have Costa Rican papers? —I ask.

—Yes! That’s not a problem. All the kids from Santa Fe cross the river every day to go to school.

We interview him just after noon, and sure enough, a boat is running a school route: dropping off younger children and picking up teenagers on the Costa Rican bank of the San Juan at shift change. It’s a boat operated by the Costa Rican Ministry of Education.

—Until we have our own school, we have to make the most of it —he adds.

The new front of colonization in the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge, warned about by Fundación del Río, has placed an increasing burden on Costa Rica to provide basic services, especially in health and education. All the settlers interviewed —as well as local residents— echo the same reality: every morning, children cross the river to attend school in Costa Rica, and return in the afternoon to Nicaragua —to the occupied territory where they live.

The Fundación del Río report asserts that these settlements develop without urban planning or access to basic services, meaning that schools and health centers are systematically absent in these illegal communities. Although no specific figures are provided, the majority of these new settlements lack both educational and healthcare infrastructure.

A day after our visit to Boca de San Carlos —and after Marvin José went to enroll his child— we headed to the Sarapiquí area. There, in the morning, we encountered two women with two young children stepping off a boat flying the Nicaraguan flag, at a makeshift dock with a bamboo railing.

—The girl’s due for a vaccine —says the young mother.

—And how old is she?

—Two —she answers, a bit warily.

—And what community do you live in?

—I don’t remember the name. It’s up there somewhere.

—And they treat you here even if you’re not Costa Rican and don’t have documents?

—Yes. Just with the ID.

—No health center over there?

—No, there isn’t.

The pattern repeats everywhere we visit during the trip. The same holds true in the San Juan Delta, where we’re headed next. DIVERGENTES requested data from Costa Rica’s Social Security Fund (CCSS) regarding healthcare provided to Nicaraguans in the border zone over the past three years, which coincides with the wave of invasions into the protected reserve. Between 2022 and 2024, Costa Rica’s public health services treated an average of over 2,500 uninsured Nicaraguans per year in the border corridor.

CCSS records show 2,660 people in 2022; 2,704 in 2023; and 2,147 in 2024. Most are adults, but there are also dozens of minors —even babies— who have received outpatient, emergency, or inpatient care. The most recent data, covering the first months of 2025, already totals over 800 cases, suggesting continued pressure on healthcare services in the areas where many of these communities are located.

However, the actual number of cases may be even higher, as the CCSS eliminates duplicates based on identification numbers within the same year. In other words, while the Ortega-Murillo regime institutionalizes the illegal occupation of the binational forest, it is the Costa Rican state that vaccinates, educates, and provides care for the settlers and their children.

Of Green Macaws and Dredging

It’s not that the forest of the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge—on the Costa Rican side—is intact. From Sarapiquí to the Delta, cattle farms abound, their loading ramps installed right along the riverbank. Cattle cross there on barges, coming from Nicaragua, after being fattened in the Indio Maíz reserve. Once on Costa Rican soil, they’re branded—given the official mark that legalizes them in a market where beef fetches a higher price. It’s an informal, almost invisible circuit—or deliberately overlooked—that crosses borders and turns a protected area into a transit zone for the cattle business.

These Costa Rican farms have been here since the 1970s, back when the country was far from being seen as a global model of environmental protection. At that time, forests were viewed as obstacles to development, and the State actively encouraged land colonization—even in environmentally fragile areas—through incentives and policies favoring cattle expansion.

But starting in the 1980s and 1990s, Costa Rica radically shifted its forestry policy. Two milestones marked this transformation: the recognition of the Caribbean Northeastern Wetland as a Ramsar site in 1996, covering areas near Boca de San Carlos, and the creation of the Maquenque Mixed National Wildlife Refuge in 2005, in the district of Pital, San Carlos. This refuge links ecosystems between Costa Rica and Nicaragua as part of the San Juan–La Selva Biological Corridor.

In Pital, we meet Ulíses Alemán, who never lets go of his binoculars—more an extension of his hands than a mere tool. He’s spent over forty years observing and meticulously protecting the great green macaw, a critically endangered bird. These macaws depend on the mountain almond tree, which still survives in this binational corridor—one of the few places on Earth where they can still nest and feed in the wild. Though, to be fair, it’s a compromised kind of freedom.

Ulíses is in good spirits. In the last macaw count, held a few months ago, 400 individuals were recorded. Despite the destruction of their habitat, cross-border conservation efforts have made an impact: back in 1994, there were only around 200. The Fundación del Río was key to that collective effort, but it fractured when the Ortega-Murillo regime revoked its legal status in August 2018. From Costa Rica, however, the organization—and this conservationist from Pital—continue their work.

You should see Ulíses’ face light up when, through his binoculars, he spots a pair of great green macaws perched atop an almond tree. They’re barely visible among the leaves until they take flight, a vibrant green brushstroke with flashes of turquoise streaking across the San Juan jungle, their raucous squawks breaking the afternoon stillness now that the settlers have put away their chainsaws.

The mountain almond is a prized hardwood. It’s tough, durable, and even used to build boat hulls. Unlike fiberglass, it doesn’t rot over time, which makes it highly valuable and one of the most sought-after trees in Indio Maíz and the San Juan reserve. The problem is, it’s also precious—essential, even—for the macaws: it’s their nesting tree and the source of their favorite food, those large, hard wild almonds that few other species can crack open. In a way, the tree also needs the macaws, who help disperse its seeds through the forest.

Mountain almond trees take 50 to 70 years to fully mature and only then form the cavities in their trunks that macaws use for nesting. A natural symbiosis, destroyed by the advancing settlers.

“If the great green macaw disappears, we’re not just losing a bird—we’re losing the entire forest,” says Ulíses, binoculars still in hand.

But in this binational forest that refuses to die—despite the settlers steadily pushing into Costa Rica—there’s more than just macaws. The Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge harbors one of Nicaragua’s greatest concentrations of biodiversity.

According to a management plan cited in a recent Fundación del Río report, the protected area is home to at least 895 species, including 303 birds—24 of them migratory—26 mammals, 15 reptiles, 3 amphibians, and over 20 species of freshwater and saltwater fish and crustaceans. It also provides habitat for endangered species listed in the CITES appendices, such as the Caribbean manatee, the jaguar, the American crocodile, the hawksbill turtle, and the harpy eagle.

In all the border communities we visited, it’s common to hear about barter exchanges between settlers and locals: they bring in bushmeat to Costa Rica in exchange for staples like rice, beans, oil, and other goods—especially when boats from San Carlos don’t make it downriver. There are so many new buildings that merchant boats now look like “floating Palí supermarkets,” as the locals put it. Amaru Ruiz, director of Fundación del Río, says that during fieldwork over the past three years, they documented recent signs of wildlife slaughter: bones of paca, wild pigs, deer, and even white-faced monkeys.

“This past year, you hardly see that anymore,” says the owner of a roadside eatery near the San Juan Delta. “They’ve just about killed everything.”

***

At first, the noise from those dredges really pissed off Humberto Ríos. It’s been ten years since he left Nicaragua and crossed into Costa Rica, settling in the San Juan Delta, where he bought a property following all the legal requirements of the neighboring country. A farm whose back boundary is the steep riverbank formed by the current as it flows out toward San Juan del Norte and meets the Colorado River. It’s like a cliffside where his cattle graze — including a Brahman bull that looks like it’s overdosed on steroids, given its pronounced musculature — unfazed by the risk of falling. Even less bothered by the roar of the red dredge engine, topped with a Sandinista Front flag. Everyone has gotten used to the noise from the engine, kept running by the Ortega-Murillo regime since before Edén Pastora’s 2010 invasion of Isla Calero, and which started roaring again in 2024, when dredging discreetly resumed without any environmental impact studies.

“I don’t even hear it anymore. It’s part of the landscape,” says Humberto, after letting us onto his farm, which offers a privileged view of the San Juan channel that leads to San Juan del Norte, where the dredge operates. “They’ve been there for a while, but I say it’s pointless. It’s like building a road to nowhere… what for? The river flows and brings the sediment back anyway. They’re just wasting time.”

The Sandinista dredges returned to the river under a veil of secrecy, removing sediment and dumping soil without any technical criteria. Environmentalists fear that beyond the supposed goal of improving navigation, the real intention is to pave the way for extractive activities and facilitate the entry of settlers into protected areas like Indio Maíz and the San Juan Wildlife Refuge, through increasingly altered river routes. After everything we’ve seen in this territory, there’s little room left to doubt that claim: at least 551 new structures have been built in the Delta.

The Fundación del Río has also pointed out that between 2014 and 2024, the Ortega-Murillo regime allocated more than $16 million USD for the dredging of the San Juan River, but budget reports lack transparency regarding how those funds were used. Amaru Ruiz, the foundation’s director, insists that this is a project carried out without transparency or prior consultation with Costa Rica, which could have negative consequences for both the ecosystem and bilateral relations.

In July 2024, Costa Rica sent a diplomatic note to Managua requesting information about the dredging activities. Ortega dismissed the request with one of his usual talking points: sovereignty. Since the works do not affect Costa Rican territory, he claimed, there is no obligation to notify San José. But in the Delta region, locals tell a different story. At the Colorado River bar, there have been reports of declining fish stocks and navigational issues, attributed to the dredging and sediment buildup from the San Juan. But in the end, the river — as the International Court of Justice made clear — belongs to Nicaragua.

The director of Fundación del Río launches his small drone one last time from Humberto Ríos’s property. The final stretch of the San Juan River reappears on the phone screen: the wide river narrows into a thin channel that flows into the Caribbean Sea, where the dredge spews sediment onto the banks. Just across, on the Nicaraguan shore, stands one of the last outposts of the Nicaraguan Army. They notice our presence and begin watching us through binoculars. We don’t feel afraid. We’re on the Costa Rican side, supposedly protected. Both Ruiz and I were stripped of our nationality and declared fugitives of justice by the Ortega-Murillo regime.

We decide to leave the Delta area, bouncing along that rough dirt road. Another afternoon falls, and from a hill that borders the reserve, Ruiz stops the truck to get one last drone shot. It’s not raining, and the crimson sky offers a parting view of this binational jungle: a forest —still dense on the Nicaraguan side— that refuses to die. A colossal canopy stretches to the warm horizon, fluffy clouds wrapped around its neck like a scarf of white mist.

—“What a fucking beautiful forest,” Ruiz blurts out, deeply moved, like someone saying goodbye for the first time.