Alexa no longer sees her future in Nicaragua. She’s 18 years old and, through hard work, was admitted to the Tourism and Hotel Management program at the National Polytechnic University (UNP), formerly known as UPOLI—one of the higher education institutions confiscated by the regime after becoming a stronghold of the 2018 civic protests. Just two months into her studies, she decided to drop out and prepare to study abroad.

“The teaching was terrible. Many professors left, others were fired, and we’d go to class just to sit and wait. There was a Sandinista flag hanging in the classroom. It’s hard being in a place where you can’t express yourself freely,” Alexa says. The daily frustration built up until it became a firm decision: to migrate in search of a better educational opportunity.

With limited resources, she began the process of apostilling her high school diploma to continue her studies in Costa Rica. “I want to study in a system where education is high quality, where politics isn’t mixed with learning. Here in Nicaragua, they’re not giving me the conditions to grow,” she says.

Apostilling is an official procedure that certifies the authenticity of a public document so it has legal validity abroad. It’s the path taken by thousands of university students and recent graduates who see the apostille not just as an official stamp, but as a way out of a country where knowledge has been replaced by the regime’s ideological indoctrination, and where academic degrees have lost their value because the system now rewards political loyalty over merit.

A Generation Forced to Leave

While there are no official figures published by Nicaragua’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the exact number of apostille requests—reflecting the regime’s broader lack of transparency—the apparent surge in this paperwork goes far beyond a mere rise in consular procedures.

For Nicaraguan academic and former university rector Ernesto Medina, this phenomenon is deeply troubling, as the country is letting go of those who should be building its future. In his view, Nicaragua is not just losing young talent; it is actively forcing an entire generation of students and professionals into exile.

“It’s very likely that this spike in apostille requests reflects the intent of many young people to continue their education abroad. This is undoubtedly a response to what’s been happening in the country’s university system, especially since 2018. The arbitrary closure of universities, under false and politically motivated pretenses, was aimed at demonstrating power and seizing total control of higher education,” Medina says.

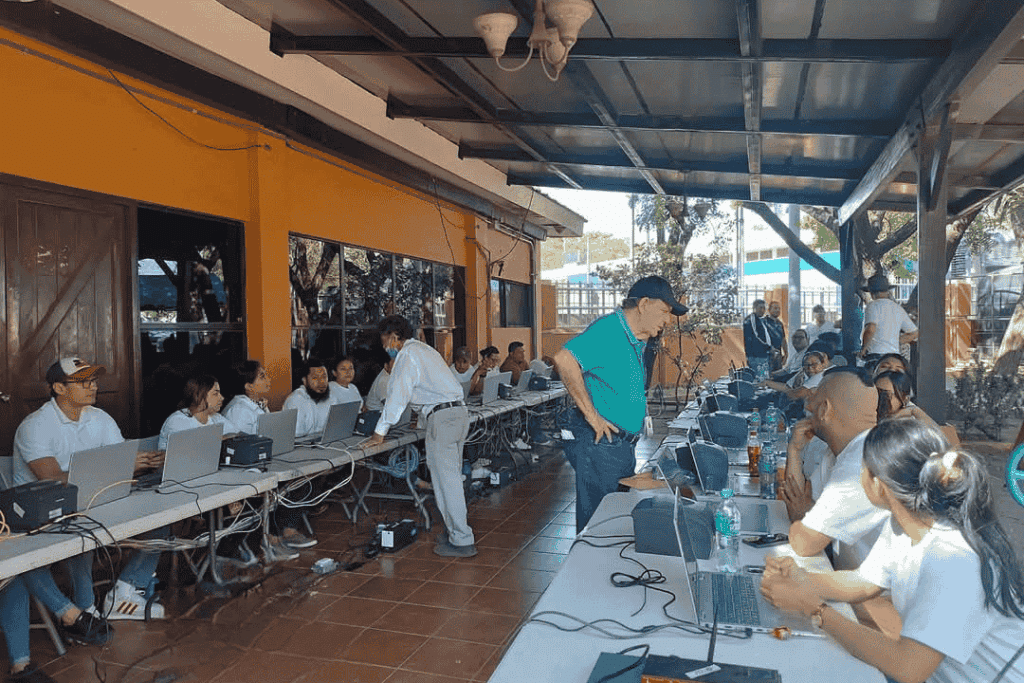

Divergentes | Taken from official media sources.

He adds that the Sandinista regime dismantled university autonomy through a strategy of political and financial control. Appointing regime-loyal authorities and using budgets as a pressure mechanism stripped universities of their essential mission. “It’s not just about changing the name of institutions—it’s a deep hollowing out of their core purpose,” Medina warns.

He explains that educational quality, already in decline for years, has worsened dramatically over the past five. In this new landscape, universities have ceased to be spaces for thinking, questioning, and creating knowledge. This is compounded by the loss of internationally trained professors and PhD-level researchers with critical perspectives, who have been pushed out of the system.

“That generation of professionals trained in the 1990s and the first two decades of the 21st century has virtually disappeared from national academia. The damage is immeasurable. Nicaragua is falling off the global scientific map,” he concludes.

Higher Education in Ruins

The report “Nicaragua’s Compromised Future: Challenges in Youth Education,” published in January 2025 by the Center for Transdisciplinary Studies of Central America (CETCAM), paints a devastating picture of the education system under Ortega’s regime.

Since 2021, 37 universities and higher education centers have been confiscated, affecting around 40,000 students. Many of these institutions, once recognized for their autonomy and academic quality, were dismantled and turned into indoctrination centers, deepening the distrust and uncertainty among young people seeking an education in the country.

The study also highlights the significant loss of teaching staff. Between 2020 and 2023, Nicaragua’s education system lost 2,428 teachers— a decline attributed to low wages, poor working conditions, and political harassment within schools. This reduction in faculty has directly harmed the quality of education and limited learning opportunities for Nicaragua’s youth.

CETCAM also notes that access to public higher education has become politicized, with students required to send official letters to the president to request scholarships—clear evidence of state control over the education system.

A Strategy to Erase the Lines

This situation is clearly reflected in the growing demand for academic apostilles. By mid-April 2025, long lines of young people were seen outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, waiting to authenticate their degrees, certificates, and transcripts.

Images of the crowds circulated on social media, prompting the regime to quickly replace in-person service with an online appointment platform, designed to eliminate visible gatherings and control the flow of applicants— a strategy already used by the Immigration Department to hide the scope of mass migration.

The new website, launched on April 16, allows users to register, receive a verification code, and book an appointment at the Ministry. But users complain of delays, frequent system crashes, and constantly changing requirements. Alexa experienced this firsthand:

“Getting an appointment is a nightmare. You spend all day on the site, and when you finally get one, it’s weeks away. Then they ask for new documents, certificates from the Ministry of Education… it all seems designed to delay you.”

Sociologist Juan Carlos Gutiérrez explains that the real motivation behind authenticating academic documents is not just the desire to study or work abroad, but a direct response to the lack of opportunities inside the country.

“Employment access is tied to political loyalty—even in the private sector, a recommendation from the local political secretary carries weight. If you’re not ‘one of us,’ the doors close,” he says. In this context, the apostille becomes a tool to escape a system that punishes professional merit and rewards political submission.

A New Online System for Surveillance

Illustration by Divergentes

Gutiérrez warns that the digitalization of the apostille process, far from facilitating it, is part of a surveillance logic. Unlike in other countries where technology is used to improve services, in Nicaragua, it’s implemented to discourage and control.

“It’s not just about organizing lines. It’s about hiding a deeper social phenomenon. Apostilling is, at its core, preparing to leave the country, and the regime knows it. That’s why they control it, filter it, and make it invisible,” he explains. By removing it from public view, they attempt to erase the image of a country pushing its youth out.

He adds that this control takes place amid a fragile economy dependent on remittances and consumption, lacking sustained foreign investment or public policies to drive productivity. This is further compounded by social cohesion shattered by repression and fear.

“In Nicaragua, even talking about education or the economy can be risky. Civil society has been broken. Thinking differently, forming associations, or speaking out can lead to persecution. When a country stops responding to the needs of its people, it stops being a homeland,” Gutiérrez concludes.

No Quality, No Trust

For university academic Adrián Meza, the student exodus from public universities reflects an uncomfortable truth for the regime: the public has lost faith in the Sandinista-imposed education model.

“This dropout rate is directly tied to the nature of the system itself. It’s not a model of science and technology; it doesn’t prepare students for employment. It’s a model that trains for political docility and submission, which clearly falls short of the expectations and needs of Nicaraguan students,” Meza explains.

Experts warn that the consequences of this brain drain are deep and silent. “We are losing productive, research, and creative capacity. Talent is leaving. Youthful energy is leaving. The chance to build something different is leaving,” says Gutiérrez.

“Most seriously, the bond between citizenship and nation is breaking. Many no longer see themselves as part of this country. The dictatorship has criminalized independent thinking and destroyed social cohesion. It has become a place people want to escape,” the sociologist states.

The latest Hagamos Democracia poll, conducted in May 2025, revealed that 63% of Nicaraguans surveyed would leave the country if they could. While young people continue to lead the statistics, for the first time, the majority of recent migrants are aged 36 to 50. This shows that it’s not just the youth being pushed out—but also the productive workforce.

In Search for a Future

This is exactly the reality Alexa wants to leave behind. She still doesn’t know if her credits will be accepted or if she’ll be able to start at a university in Costa Rica anytime soon. But one thing is clear: staying is no longer an option.

“They’re not giving me the conditions to grow here. I’m afraid to leave, yes. But I’m more afraid of staying stuck in a system that denies me the chance to be someone.”

“I’m not ruling out coming back, but to be honest, I don’t see myself returning anytime soon. There just aren’t many opportunities to grow here—not if you think differently. I want to study in a country where my work matters, where I can have a stable future,” adds the young student.

Every day, dozens of young people like her log on to the Ministry website, fight for an appointment, fill out forms, pay fees, and gather documents. They’re not just seeking a stamp—they’re seeking a future. And each apostille that’s signed is a silent act of breaking away from a country that is pushing them out. A country that, instead of nurturing its professional talent, expels it.