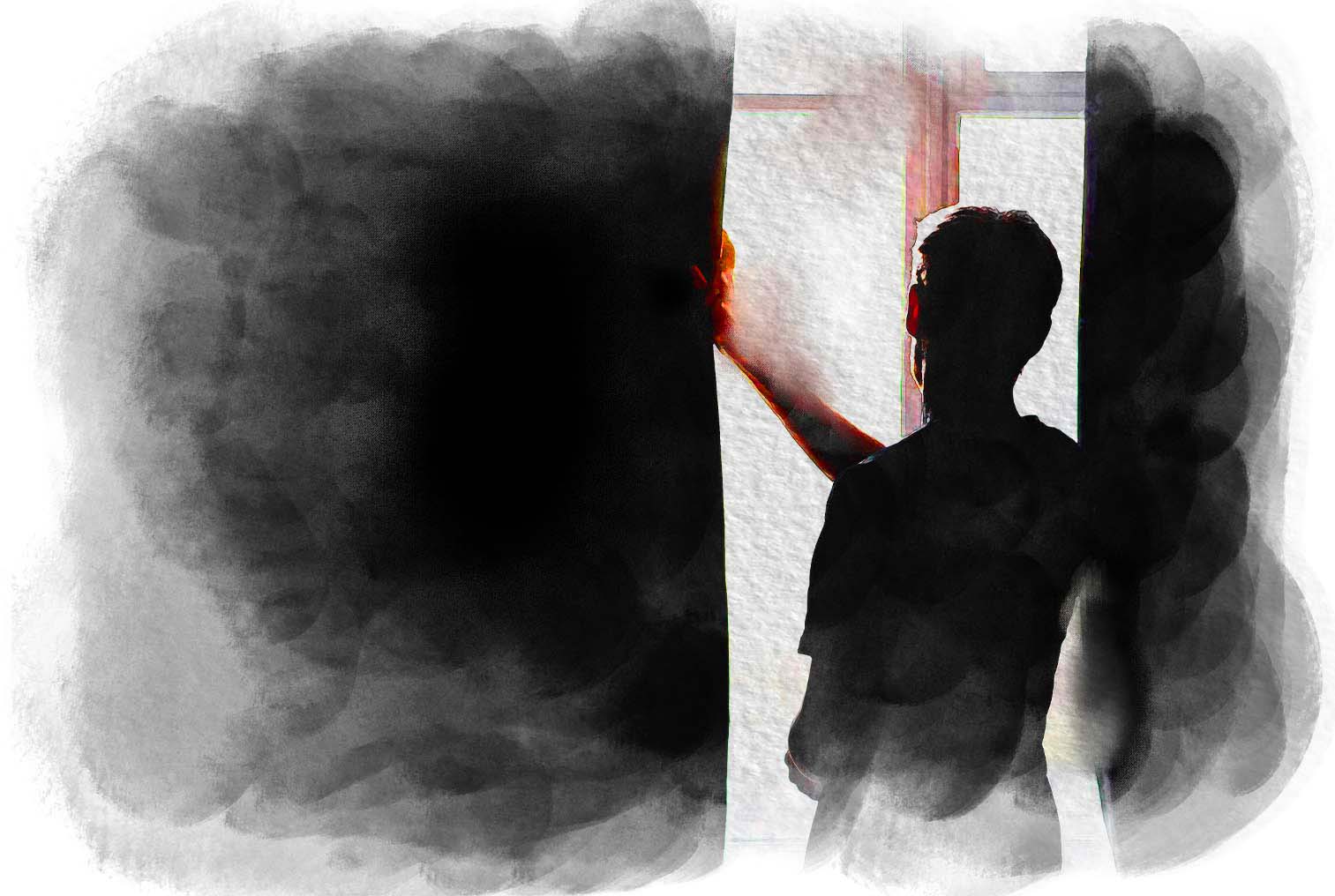

Physical aftermath,

a sign of political violence

Nearly three thousand kilometers away from Cerna, in a colder and more distant land, is student activist Samantha Jiron. Passionate about political science and communication, and marked by a strong sense of justice. She was the youngest female political prisoner held by the dictatorship until February 9, 2023.

Like many, she was captured in the year of the electoral fraud, the year in which for the fourth consecutive time Daniel Ortega declared himself president of Nicaragua, with all his electoral competitors locked up in jail or in exile.

Like other exiled student activists, Jiron's post-imprisonment health is an issue. With difficulty, due to a severe cough that attacks her, she says she is recovering from an unexpected surgery. Her left ovary was twisted and she needed immediate surgery.

"Just like that, it twisted out of nowhere," she says. The twisting of her ovary happened in October 2023, just a few months after her partner and also an exiled political prisoner, Kevin Solis, experienced a facial paralysis "out of the blue".

However, this is no coincidence. Jiron knows the origin of all their ills: the after-effects of being in the regime's dungeons, deprived of medical attention and any other humanitarian needs they required at the time.

She, who has always been in good health and had few medical problems, spent her last year in the United States riddled with illnesses, discomforts and worries.

"It's completely after-effects and I'm a witness to that," she says. "I have had many health problems, both while in prison and after my incarceration," she says. These are the manifestations of physical, emotional and mental damages of being unjustly deprived of liberty for more than a year.

The first consequence she noticed is her inability to be in closed spaces, even if it is a car or a bus. "My blood pressure drops, my blood sugar drops, I turn pale and I feel like I'm going to faint," she says.

Surprised by her reactions, she went to a doctor to find out if the reason was a blood pressure problem, but the doctor told her that it was all an emotional reaction to experiencing confinement again.

"I had never been through this before I was in prison. I've never had these medical problems before," she says. To reduce the constant discomfort, she wears a special bracelet that regulates her blood pressure. Although she still has anxiety attacks, with this device she can at least control them.

Because of the special protection that Jiron has with the humanitarian parole - which the rest of the 222 exiles also have - she has an insurance called Medical, which is available only for the state where she lives, California. So her surgery and postoperative treatment, which cost $89,000, was not paid for by her. "Getting sick here is the worst thing that can happen to you," she says.

Even in the midst of all the problems, she laughs and says that when her boyfriend, Solis, suffered the facial paralysis that cost more than $20,000, they were joking about fleeing the country if the insurance company did not pay the hospital bill.

The young student says something that all the other banished people endlessly repeat: "that they sent us to the United States doesn't solve our lives."

"Many say that they made it easier for us because we came here, but that's not the case," she emphasizes. Due to her constant medical problems and to improve her health, Jiron decided to quit her job at the company where she worked.

There, many of her responsibilities involved physical effort. In addition, as in any other place in the North American country, if she did not have at least one year working, she had no right to receive compensation for her rest and recovery days.

"We have little time to work (my partner and I). In these companies they don't give you a leave for full recovery, not in this company at least. A job is not worth your health deteriorating," she adds.

She says that the month in which Solís was paralyzed, she was unable to work for several weeks and therefore did not even receive half of her salary. Her insurance only covers medical expenses, but does not cover the lost work days.

The space where she lives alone costs $1800 and it is not even an apartment. It is a studio apartment with no rooms or partitions. It only has a small bathroom and a laundry room that simulates a kitchen. It is enough to look around to see the whole space.

Exiled and now a foreigner in another country, these are elements that intertwine to make it difficult for her to find a job that will allow her to afford a better place. "It's very difficult to get a job here, even if you're a professional. It's not like I'm a journalist and I'm going to work in a media outlet here. The jobs for us are different," she stresses. "Us," meaning the banished.