Abigail trembled uncontrollably when she saw the police officers at her house: there were so many of them, rummaging through drawers and closets, searching for electronic devices and leaving a trail of destruction. She felt a fear she had never known in her eight years of life, a fear that paralyzed her. She just kept trembling and trembling, fragile like a little bird’s leg about to break, especially when the officers repeatedly shouted her father’s name: “Where is he?” “Wheeeeeere?” And at her feet, unnoticed by Abigail, was her little sister Sofi, four years old, crying and seeking refuge, trying not to watch as this storm of uniformed men harshly interrogated their grandparents—her beloved grandma and grandpa. Both girls were a bundle of nerves, terrified in the face of the political violence perpetrated by the agents of the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo regime.

The police confiscated the grandparents’ and Abigail’s cell phones. Abigail’s was a Xiaomi she used to practice English on the Duolingo app, watch videos, and talk to her aunt who lives abroad. The leader of the police operation sent a message to her father from the grandma’s phone, asking him to return home urgently, saying something had happened with the girls. It was an unusual message for the father, who shortly after arrived home and saw the patrol cars outside. At that moment, he knew it was about more than just his daughters.

The father was beaten in the yard of the house. The police slammed him to the ground and handcuffed him. Abigail and Sofi saw everything: every punch, every shove, every shout… One trembled more and the other cried more as they got their dad into the police car. He was arrested for being considered an opponent of the Ortega-Murillo regime and their political project, a totalitarian dictatorship that crushes all dissent, without regard for the presence of minors during increasingly aggressive arrests.

The sisters didn’t stop crying that night, unaware that they would soon lose their mother too. The next day, the mother went to inquire about her husband’s whereabouts and condition, but instead of getting answers, she was arrested. The couple was detained in the first half of 2023 for their political activism on social media. Since then, the girls have been in the care of their grandparents—a de facto orphanhood imposed by political imprisonment, causing severe emotional impacts, especially on children.

As of June 30, 2024, the Mecanismo para el Reconocimiento de Personas Presas Políticas reports 147 political prisoners in Nicaragua (in August, the number rose to 151). Of these, at least 36 are parents. A report by the Unidad de Defensa Jurídica (UDJ) reveals that these 36 individuals have 69 minor children. The report measures the impact of political imprisonment on the children of political prisoners through closed interviews.

The sample analyzed by the UDJ includes 37 minors, including adolescents. Thirty-five percent of them witnessed the violent arrests of their parents, like Abigail and Sofi. For security reasons, we use pseudonyms to refer to these sisters and their family. In less than 24 hours, the two girls lost both their father and mother. This forced orphanhood has lasted more than a year. The crying, the first stage of trauma, is still there, especially in Sofi. When she’s not crying, the little girl has episodes of desperation. She looks for her mom and dad but can’t find them.

Sofi’s relatives tell me that she often asks, almost every day, when her parents will come home. They try to console her, but at that age, comfort starts to lose its effect as the days go by, and she begins to understand—as Abigail understood from the day of the arrests—that mommy and daddy are imprisoned and condemned.

“I’m a sad child,” Sofi often says after visiting her parents in prison. The sporadic family visits end with the sisters’ inconsolable tears. When Sofi calms down, like the afternoon I spoke with the family after they had just returned from a visit to the women’s penitentiary, the little girl is quiet, disconnected from her surroundings, disoriented, and still teary-eyed. She is, I think without saying it to the family, exactly what she says she is: a sad child. I wonder—again without saying it to the family—is this what sadness looks like at four years old?

***

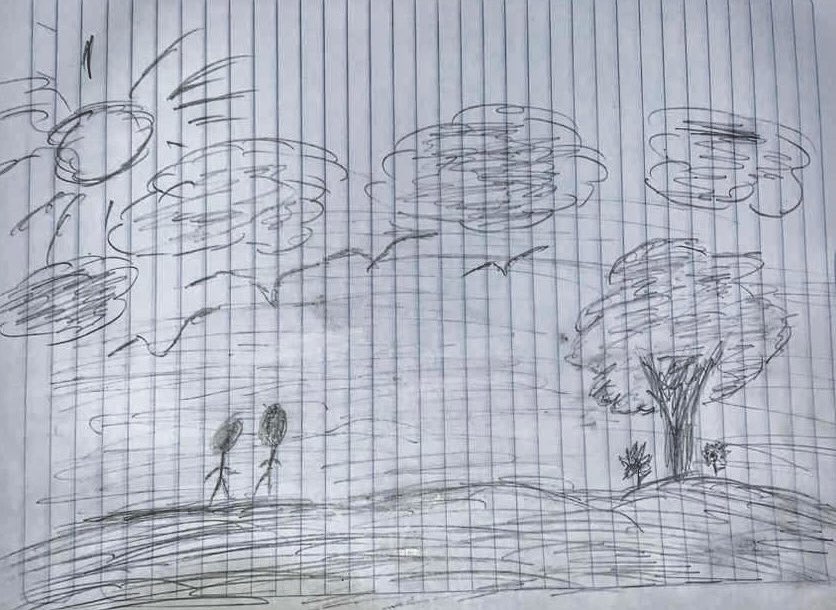

Maybe Sofi expresses herself through the drawing the therapist asked her to make for the UDJ report: there she is, along with Abigail, daddy, mommy, her aunt, grandma, and grandpa. They’re all holding hands. The family is smiling. But then something changes: a line becomes chaotic, bouncing up and down, zigzagging over itself, and at times, turning into a messy blur. The family and their smiles fade from the page. An airplane without wings and a bus with three wheels appear. Are they all inside the airplane? On the bus that takes them to the prisons for family visits? Where are they going? Are they fleeing? Where did they go? What is Sofi trying to say?

The psychologist analyzes Sofi’s drawing: “There is a need for affection and family belonging; desires to escape, repressed anger, avoidance of reality, grief, and feelings of abandonment.” Sofi is suffering from a “depressive reaction.” Depression at four years old.

***

The hardest part is the birthdays. Abigail feels them deeply. She celebrated her eighth birthday with her parents in prison when they allowed family visits. Although she can hug her mom at the women’s prison, it’s different with her dad: she can’t touch him because it’s not allowed at La Modelo prison. Feeling your parents’ touch is crucial during early childhood. Abigail tells me she’s had “the urge to take a hammer and hit” the police officers and the lock on the cell so her dad could get out. So she could hug him and hear him say, “Happy birthday, my girl…” It moves me because she’s so delicate. I don’t think she could handle a hammer easily. The only thing she could take to the prison was a small cake to sing “Happy Birthday,” which was cut under the watchful eyes of the guards.

The UDJ reports that, besides birthdays, the children of political prisoners have missed other important moments in their childhoods: “24.32% of the minors have had school graduations without their imprisoned parent being able to witness the event. In this sense, one of the main impacts on children due to family separation caused by political imprisonment is on their mental health.” A wound that Abigail already feels in many ways, starting not just with her birthday, but also Sofi’s, her mom’s, and her dad’s. All the family birthdays she has spent apart from her parents.

Abigail misses the family birthdays and the trips her parents used to take them on to continue the celebration. They would usually go to the beach or to Managua, the capital. She will turn nine next September, and for months now, she’s been saying she doesn’t want to have a birthday. She doesn’t want to cut two more small cakes separately at La Modelo and the women’s prison La Esperanza. She doesn’t want another birthday without her parents. She doesn’t want to wait so many hours to see her mom and dad. She doesn’t want those grim-faced guards at the prisons to search her, to scrutinize the cakes… She doesn’t want any of it.

Visits for the families of political prisoners are exhausting: they are constantly harassed, searched—sometimes even in intimate areas—and blackmailed by the guards, who don’t allow them to be alone with their loved ones. It’s no different for the children. The report by the Unidad de Defensa Jurídica (UDJ) states that more than 50% of the minors analyzed have been subjected, at least once, to long hours of waiting in the prisons before the visits.

“No child of a political prisoner in Nicaragua is allowed to see their parents for more than an hour, once a month, in prison. Family visits take place surrounded by guards who position themselves with their weapons just a few feet away, intimidating the families and eliminating any privacy during the visit,” the UDJ report denounces.

“During the arbitrary imprisonment of their parents, 13.51% of the minors have not been able to visit their detained parent because the state authorities have denied them the opportunity. Additionally, 35.14% haven’t visited them for personal reasons… Most of those who have managed a family visit end up crying uncontrollably when it’s time to say goodbye. In one case, a child even grabbed their mother’s hair, refusing to let her go.”

Abigail hasn’t gone that far, clinging to her mom’s hair after a family visit, but something has changed with her own hair: she hasn’t combed it in many months. “She gets anxious after her bath because her mom isn’t there,” one of her relatives tells me. “She won’t let anyone comb her hair, and barely puts it in a ponytail. When I ask her why she doesn’t want to do her hair like before, she says no, because her mom used to comb it and tell her how beautiful she looked… but now she doesn’t have a mom to say that, to tell her she looks pretty with her hair done.”

Since her parents were imprisoned, Abigail has stopped talking as much. Her chatty side is gone, both at home and at school. At home, she used to talk about what she’d studied at school, how her grades were, what she’d discussed with friends, or show off photos with them during recess. She was a lively girl. But now she’s withdrawn, usually breaking her silence with rebellious behavior toward her grandparents, who are now her caretakers. The same happens at school: she’s distanced herself from her classmates, and her grades have dropped from an average of 98% to 80%. And they keep falling. Abigail is depressed, her family says.

The UDJ report has identified that 67.57% of the minors analyzed not only cry constantly over everything related to their parents’ arbitrary detention, but 8.11% have had suicidal thoughts. Additionally, one teenager has turned to drugs following the various impacts caused by the arbitrary arrest of their parent. “43.24% of the minors have required psychological or psychiatric attention due to the damage to their mental health caused by the situation of injustice,” states the organization, which operates from exile. “This number could be even higher, but many families don’t have the time or money to take them to a psychologist.”

Abigail knows her mom was sentenced by the Ortega-Murillo regime. Her family says that learning about the sentence hit her hard. “At first, she asked why her parents were sentenced to so many years in prison. We explained everything, that it was a political issue, unfair… Then she asked us, if they were innocent, as we said, why were they still locked up? We didn’t know how to answer. So now, imagine an eight-year-old with these kinds of prayers: every night, she prays to her guardian angel and says the Lord’s Prayer for her parents and the political prisoners… It’s a strange situation, you shouldn’t have to pray for that at that age,” her relative reflects.

***

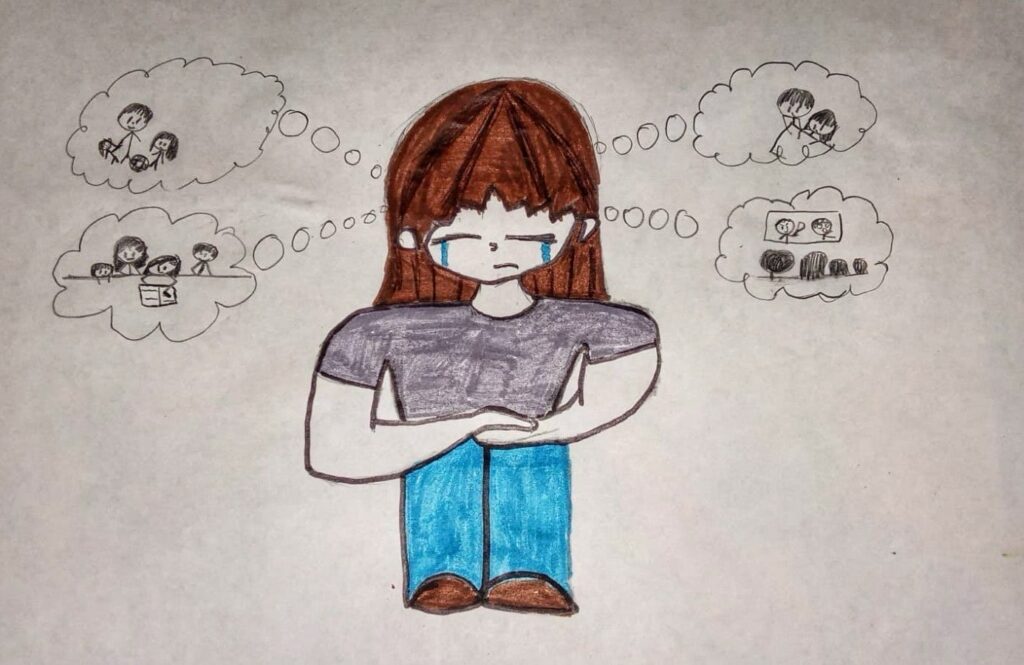

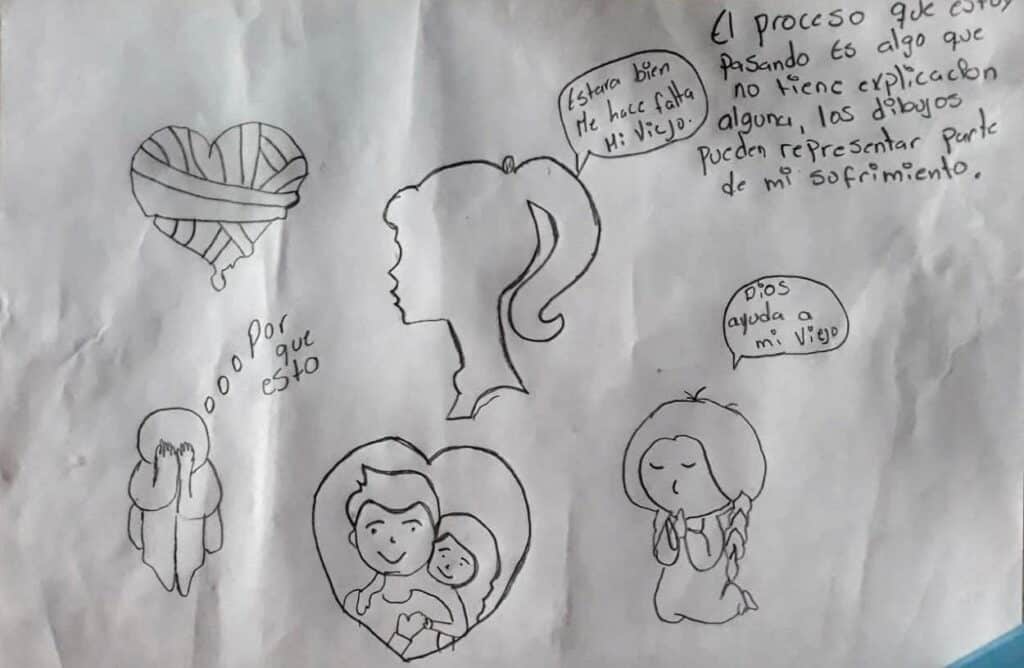

The girl in the drawing is Abigail. She’s more explicit than her little sister, Sofi. She drew herself crying, in a posture of anguish. Surrounding her tears are images of her parents, her, and Sofi, engaging in various activities: kicking a ball, studying, watching TV… all the things they can’t—and won’t—be able to do together while her parents continue serving their eight-year political prison sentence imposed by the Ortega-aligned judges.

The UDJ psychologist analyzes Abigail’s drawing: “It shows melancholy, emotional pain, a rupture in her sense of belonging, longing, and grief over the loss of family bonds; a fixation on past memories, resistance to the future, broken psychological defenses, helplessness, mental fatigue, a need for affection, repetitive thoughts about past experiences, and a rigid attitude as an attempt to control her internal situation or passively resist external pressures. Possible post-traumatic stress with concurrent chronic depression.”

***

Abraham left behind several debts. Even though he was imprisoned by Daniel Ortega’s regime for his political views, the bills keep coming to the house. Debt collectors have no qualms about such situations. Don Abraham’s wife had to face the debts alone, but her salary as a domestic worker in a middle-class neighborhood in Managua isn’t enough to cover everything each month—not for the bills, nor for what their two children, Socorro, 15, and Joel, 16, need.

While the arrest of their father was a traumatic experience for both teenagers, what they’ve felt most is the change in their everyday lives, especially Socorro. Since late 2023, she no longer has recess at her high school. While her classmates enjoy their recess, she started working at the school’s store, serving students who buy snacks. She earns 30 córdobas a day—about 83 cents at the official exchange rate. It’s just enough to cover her commute to school and buy some small items, but not enough to significantly contribute to the household.

Socorro says she isn’t ashamed, but she doesn’t feel comfortable working at the school’s store either. She’s simply stuck in an uncomfortable situation that she can’t escape for now. Although she’s received a couple of taunts from her classmates, she says she has no choice but to keep doing it. The UDJ report reveals that 35.14% of the children of political prisoners have been bullied at school. Besides being mocked because their parents are called “criminals,” the most alarming statistic is that 24.32% of the sample had to drop out of school due to bullying, which leads to depression and combines with economic problems, as is the case with Abraham’s children (a pseudonym used for security reasons).

In the mornings, before heading to school, Socorro helps her mom at the house where she works as a domestic assistant. There, she assists her mom and earns a small wage. Every little bit counts for this family, which used to rely heavily on Abraham’s income. For several years, he worked as a driver and later sold bread after the Ministry of Education barred him from teaching in the public school system in 2015 due to his criticism of the Sandinista government.

Joel has started looking for work at the auto repair shops in his neighborhood, but he hasn’t had any luck. He’s thought about leaving the country to try his luck elsewhere, maybe in the United States, but the family doesn’t currently have the money to pay for a coyote to take him across the border illegally. Finances are tight at home, and on top of that, there’s the cost of sending daily food packages to Abraham in La Modelo prison (according to the UDJ, having a family member as a political prisoner costs families an average of 6,900 córdobas per month, equivalent to 196.5 US dollars).

Political imprisonment significantly impacts families economically, and minors are not exempt from this. The UDJ report reveals that 10.81% of the minors studied were forced to start working as child laborers. This means they either dropped out of school or compromised their education, like Socorro. These minors are typically between 14 and 18 years old—teenagers.

“According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), child labor includes tasks that interfere with schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school, forcing them to drop out prematurely, or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. After their parents’ imprisonment, children likely had to take on new roles at home to support domestic tasks as well as the family’s emotional and financial needs,” the UDJ report highlights.

The document’s findings show that political imprisonment has worsened poverty in families due to the drastic reduction in their income, as well as an increase in expenses (prison visits, packages, medicines for the inmate, legal costs, transportation, etc.). “In other words, the poverty and consequent child labor experienced by children and adolescents stem from the lack of income in their households, difficulties in accessing basic services, and other factors linked to survival, discrimination, and exclusion. Poverty makes them more vulnerable to not exercising their basic rights enshrined in international resources,” the UDJ states.

Socorro continues to alternate between helping with her mom’s work and working at the school. She tells me that she doesn’t mention any of this to her father, Abraham, so he doesn’t get even more depressed in his cell. “And I definitely don’t tell him that my brother wants to leave the country,” she says.

***

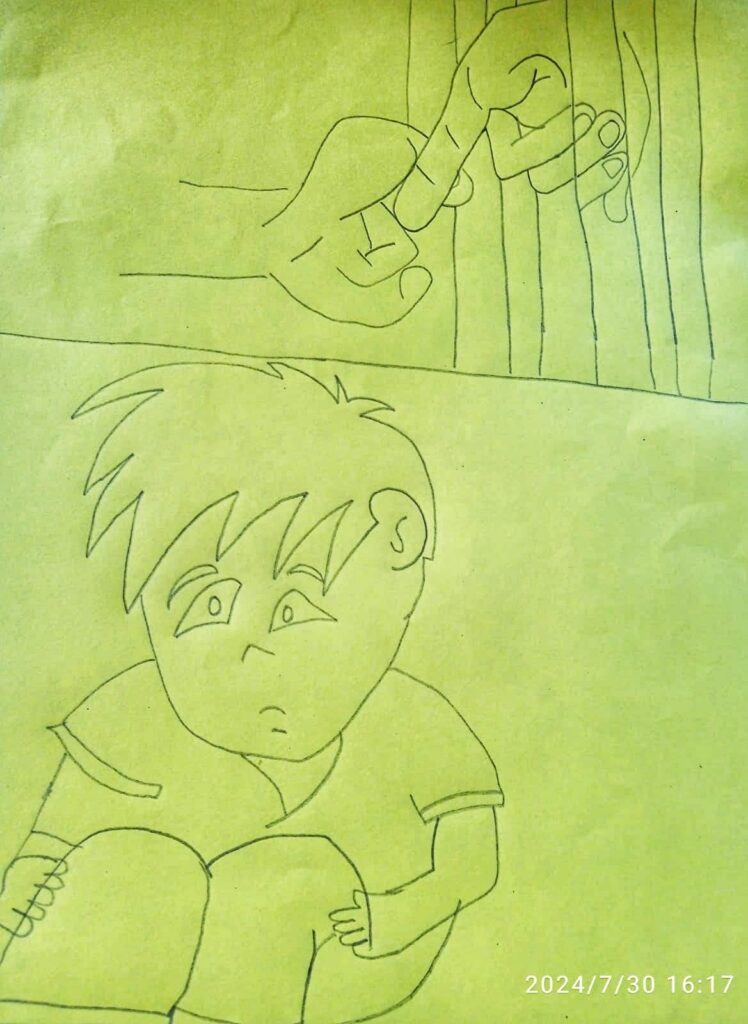

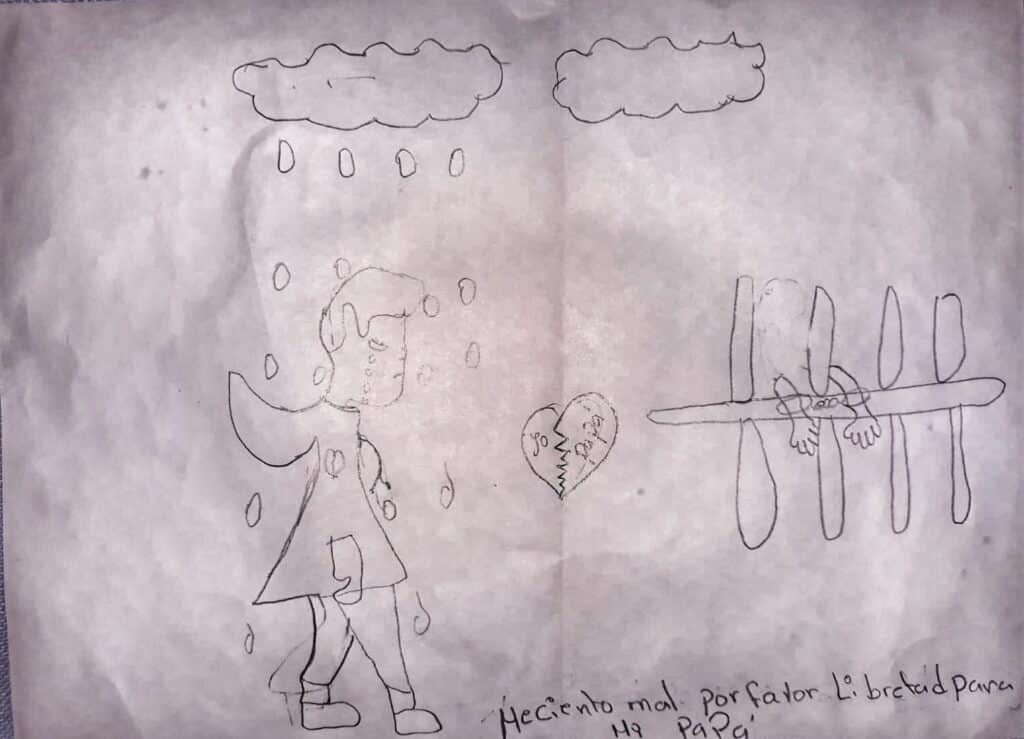

The drawings by Socorro and Joel raise complex, fundamental questions: “Why this?” They miss their father. It’s a tough situation for the siblings. Broken and patched hearts.

The UDJ psychologist interprets the adolescents’ drawings. For Socorro, the analysis is: “Signs of anxiety, separation distress, helplessness, psychic energy deficit, high level of psychoaffective sensitivity, hypervigilance, mistrust. Defensive attitude, repressed desires, low psychological defenses, social maladaptation, anxiety about everything being done, attempts to avoid being seen, to escape the pressure from those around us, and a form of fleeing from dominant individuals or unpleasant realities that cannot be confronted.” For Joel, the analysis reads: “Acute mixed anxiety-depressive syndrome, lacking defense strategies, fear of social spaces, helplessness, and contained anger.”

***

The UDJ report asserts that the vulnerability of these children and adolescents is amplified not only by their parents suffering state violence through political imprisonment but also because this forced de facto orphanhood exacerbates poverty, school dropout, child labor, displacement, drug addiction, stigmatization, and discrimination in their educational and community environments. Experts in psychology point out that all of this has a short, medium, and long-term impact on their lives.

There’s more: during the arrests of Abigail and Sofi’s father, the police didn’t just confiscate phones, but also the children’s toys. The same happened to 18% of the documented minors: officers seized plastic dolls, water guns, inflatables, toy cars, little soldiers… among other harmless toys.