On August 13, 2021, the day the National Police confiscated the building of the newspaper La Prensa on orders of the Ortega-Murillo regime, Octavio Enríquez, one of Nicaragua’s most prominent investigative journalists, felt that the dictatorship was trying to tear away part of his memories. Although at the time Enriquez was not part of the staff of this media outlet, his past as a reporter, in different periods for more than 20 years, made him nostalgic when he heard the news.

“One feels that a part of you leaves with everything that happened. I mean, remember that we arrived at that facility when we were very young. We were formed, we met dear friends, and in my case, my wife”, says Enríquez from San José, Costa Rica, where he went into exile a few years ago to continue his work, now at Confidencial.

Enríquez nostalgically recalls the confiscation of La Prensa’s facilities. The first thing that came to his mind were those first times he had to write a news article. He also remembered the investigation that exposed the hidden enrichment of former Interior Minister Tomás Borge. Many of the stories he published had an enormous impact on Nicaraguan society. He thought, then, of the importance that the printed newspaper had on citizens.

“Printed newspapers, such as La Prensa, play a crucial role in society by being independent media that investigate and monitor power. In countries where institutions have failed or have been corrupted, the independent media become responsible for holding power accountable and revealing irregularities, enrichment of the ruling class and human rights violations,” he explains with conviction.

In the specific case of La Prensa, says Enriquez, its importance lies in its long history of confronting different dictatorships and its fight for freedom in Nicaragua. Despite persecution and the difficulties imposed by the Sandinista regime, the newspaper continues to work from exile to provide the population with information.

Gabriela, another journalist who worked for more than 15 years at La Prensa, said that the printed newspaper was a thermometer that measured, in a way, the pulse of democracy in the country. Having it, even in these times when the Internet is the main platform for expansion, meant respect for freedom of expression.

“That is why still, despite the Internet being the main platform, every country in the world has a printed newspaper. And the only ones that do not have them are countries like Nicaragua, which disappeared not because the market eliminated them, but because the State destroyed them and took them out of circulation as a political and repressive measure”, said Gabriela.

For Enriquez the printed newspaper was very important for several reasons: the first one because it was a symbol of tradition, it has an important informative weight and became a symbolic item due to the regime’s efforts to silence it.

“The cancellation of the daily circulation of a newspaper like La Prensa in remote areas of the country had a significant impact. In a context where technology and digital platforms are booming, printed newspaper was reaching a group of readers that possibly did not have access to the digital version,” says Enriquez.

The loss of the printed newspaper has meant the disappearance of a unique experience that fostered conversation and debate in Nicaraguan homes, according to the journalist.

Investigations by La Prensa

The newspaper has a long tradition of investigative journalism. From the times of Arnoldo Alemán to the present, the newspaper has been recognized for its courageous work in exposing illicit acts that have affected society and public funds.

During former President Arnoldo Alemán’s administration, La Prensa was the first to expose corruption cases, such as the scandal of “Los checazos” (fraudulent checks), becoming a reference for investigative journalism in Nicaragua.

With the publication of “Los checazos” case, it was revealed how the former General Director of Revenues, Byron Jerez Solís, ordered to issue credit notes to the Nicaraguan Telecommunications Company (Enitel), through the General Directorate of Revenues (DGI), to later convert the credit notes into checks and pay with cash up to 46 million córdobas to companies, corporations and individuals related to the former official, during the period of 1998-2000.

“At a time when social media were not yet predominant, the impact of La Prensa’s investigations allowed to generate public debate and question the system’s flaws, exposing corruption and promoting greater transparency in the management of state resources”, explained Gabriela, who added that, at that time, the newspaper provided a space for citizens to denounce anomalies in addition to serving as a voice for public officials who wished to expose public irregularities.

Gabriela says that it was much better at that time because of the possibility of interviewing officials and accessing information more openly compared to today. Journalists developed a work plan, collected information and had a recognizable building where sources could come to denounce.

“This physical proximity made it possible to establish direct and personal contact with sources, providing trust and facilitating the exchange of relevant information,” commented this journalist, who spoke to DIVERGENTES under a pseudonym for security reasons.

However, it is important to note that the practice of investigative journalism has always been risky and under the watchful eye of the people in power. Although there were challenges at that time, the current situation presents abysmal differences due to the persecution and harassment faced by the independent press, as well as the limitations imposed by the pandemic. Nowadays, information gathering and denunciation have become more impersonal, taking place through screens and social media, which makes direct contact and the echo of denunciations more difficult.

“During the Enrique Bolaños administration, La Prensa focused on reporting on the poor execution of government projects and budget under-execution. Through its investigations, the newspaper uncovered cases of mismanagement and lack of transparency in the implementation of projects, which implied a waste of resources and harm to Nicaraguans. These revelations contributed to demystify the image of an impeccable government and highlighted the need for greater accountability,” said Gabriela.

In 2007, she explained, La Prensa also played a crucial role in investigating the first acts of corruption by the Ortega-Murillo regime. The newspaper denounced the expansion of the Alba group and revealed that the oil agreement between Nicaragua and Venezuela was manipulated by the Ortega-Murillo family for their own benefit. The state agreement, which turned out to be a private arrangement between the ruling family and the Venezuelan government, impacted public opinion and undermined confidence in the government.

This control work was one of the main reasons why the regime decided to reduce to a minimum the impact of La Prensa on the Nicaraguan population. It was not only the increase in taxes, but also the withholding of paper and later the persecution of journalists, directors and, finally, the confiscation of the building where the newspaper was printed.

“What this dictatorship did has not been done by any other repressive regime that has existed in the history of Nicaragua, that is to say, none persecuted independent journalism as much as Orteguismo has done. The Press, in Somoza’s time, suffered violent attacks, but it was never confiscated or expropriated as it is now. The desire of the Sandinista government was to make it disappear and get rid of a reference of journalism”, says Gabriela, who assures that, in spite of repression, the regime has not succeeded in making the “Paper Republic”, as La Prensa is called, disappear.

Working from exile

Despite the regime’s efforts to weaken and silence La Prensa, the newspaper has maintained its professionalism and commitment to freedom of expression, although it is now doing so from exile.

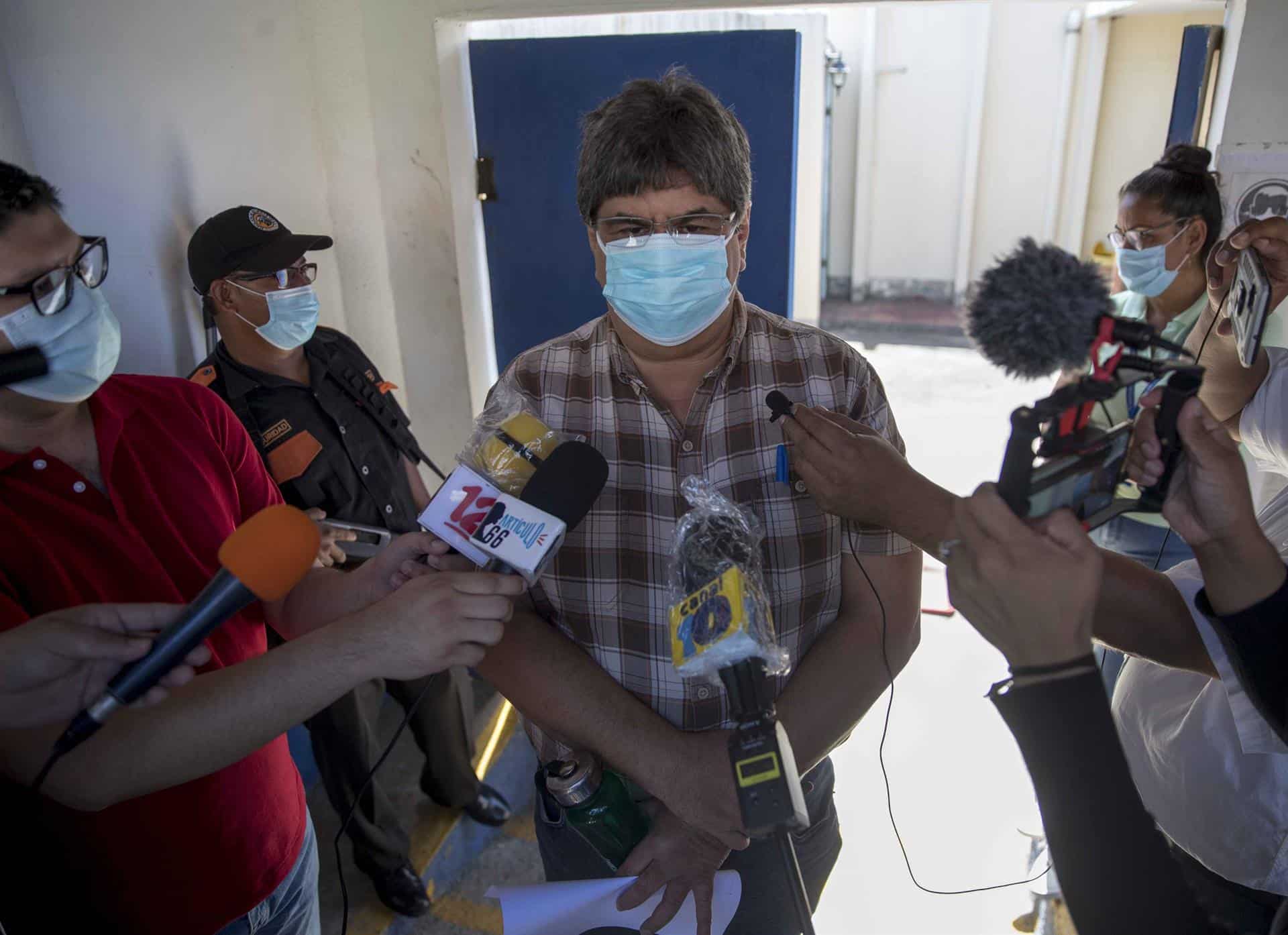

Rubén is a La Prensa journalist who had to go into exile and now works in Costa Rica. He confessed to DIVERGENTES that it is complicated to do journalism from abroad, but that it is the option they have to continue fulfilling that work of service with which he grew up while doing reporting work in the country.

“Being far away affects you in that you can’t be there when the facts happen, for example. It is not like before when you went to a market or supermarket and you could see how the price increase affected the basic food basket,” he said as an example.

Rubén, however, considers that social media and the advance of new technologies make it possible to overcome some of the shortcomings they have from exile. For example, talking to sources is safer via Telegram or WhatsApp, or obtaining photos of events that are shared by network users who continue to believe in the work of journalists.

“I want to return to the country but it is complicated by the persecution that all of us who work at La Prensa have. I hope that one day we can return and do journalism as before, or even better thanks to new technologies,” he said.

On the other hand, Enríquez, also in exile, remembers with great nostalgia his last period at La Prensa. During those years he was editor of several sections. Through his computer passed hundreds of notes written by colleagues who told how the Sandinista regime repressed and imprisoned demonstrators who opposed the dictatorship. “It was my turn to put together the first page of the newspaper, which dealt with the murder of an entire family in the Carlos Marx neighborhood in Managua. An extremely painful event,” he told DIVERGENTES.

“The regime has lost credibility and support, while it tries to magnify its narrative through false social media accounts”, says Enríquez, who confessed that, when he observed the images of the confiscation of the La Prensa building, far from being discouraged, he understood two very important things about the work of the media: “One, that La Prensa will continue despite the adversities and that it is already part of the conscience and national history. Two, that it has earned a respect and admiration that, far from fading, has continued to grow because of its commitment to tell what is happening in the country”.