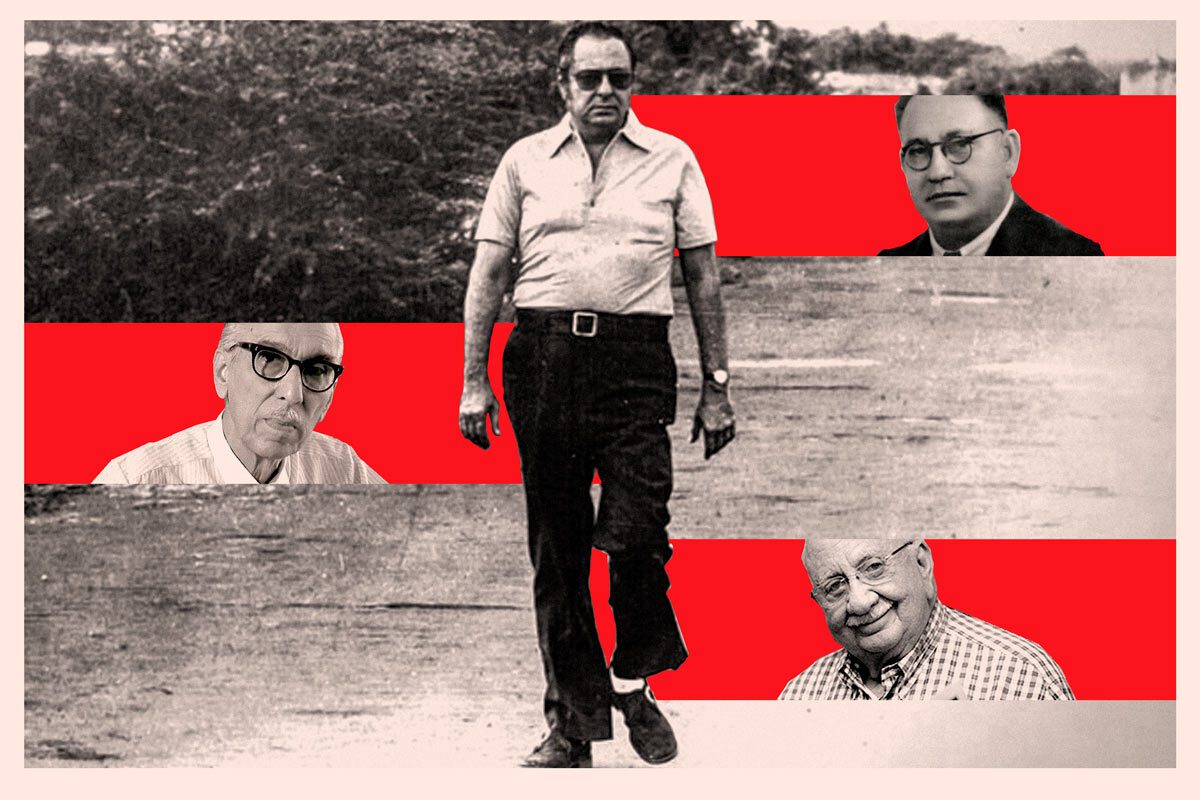

On January 10, 1978, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, director of the newspaper La Prensa for 26 years, was shot to death by hired assassins while driving his car in Managua. Under his leadership, the newspaper reached its highest level of impact on society. Pedro Joaquín Chamorro has since become known as the “martyr of public freedoms” and many Nicaraguan journalists draw inspiration from his legacy.

The assassination of Chamorro Cardenal is the largest attack against an editor of the newspaper La Prensa. But this aggression was not the first nor the last against its directors. His father, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya, had to go into exile because of threats from the regime of Anastasio Somoza García, the first dictator of this lineage. And more recently, two of Chamorro Cardenal’s sons and a nephew respectively, Cristiana, Pedro Joaquín, and Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro, were imprisoned in 2021, and banished two years later by the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. In addition, the newspaper’s facilities – which were bombed by the Somoza dictatorship in 1979 – were confiscated by the current regime.

Exile, trials, imprisonment, torture, confiscations and even banishment and suppression of nationality are part of the aggressions suffered by the directors of this newspaper during almost a century of existence in Nicaragua.

Don Pedro’s exile

Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya was the pioneer of the family in directing La Prensa. Grandson of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Alfaro, who was president of Nicaragua, and father of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, Chamorro Zelaya acquired the shares of La Prensa in 1930, four years after the newspaper was founded by Gabry Rivas, Enrique and Pedro Belli.

Don Pedro’s La Prensa was conservative, with a peculiar taste for Nicaraguan history. “A platform for teaching ethical and patriotic values”, as defined by historian Emilio Álvarez Montalván. It was neither a financially successful enterprise nor of great influence in politics, as it happened later, under the direction of his son. “The essential task was not to obtain large profits, nor was it seen as a confrontational trench or as a disseminator of scandalous events”, summarized Álvarez Montalván, in his text “La Prensa de don Pedro”.

La Prensa at that time was located in an old building on El Triunfo Street, in old Managua, which did not even have a wall clock. The newsroom measured 5×5 meters, located a few steps from a street where all the noises of people, cars and carts could be heard. Staff and visitors could enter without any control. Don Pedro’s office could even be entered at any time.

The editors were seated around a rustic table, where they wrote their texts with a pencil. Then, the texts were picked up by other people, who stood up and placed the printing casts upside down, to then take out the proofs with an inked roller that was checked by proofreaders. There were a maximum of four reporters and three administrative support staff.

The newspaper consisted of three pages: a hinge with a page in the center. Its contents were notes of social life, religious chronicles or political events, which could not anger Somoza García. However, this newspaper, which was published in an almost primitive form, and whose content was parochial, was closed on several occasions. In one of them, the cause was an alleged lack of respect to the first lady, Salvadora Debayle, wife of Somoza García. The reason: in a report on a Catholic procession it was written that the absence of the first lady, who used to attend every year, had not detracted from the solemnity of the event.

The reasons for the closure of the newspaper were diverse and peculiar. For example, because the reports on the poisoner of Leon, Oliverio Castañeda, a character in the novel Castigo Divino, by Sergio Ramirez Mercado, “raised people’s spirits”, that is to say, made them nervous. But at other times, Somoza’s guards would close the paper for no reason. The longest period that the newspaper was closed was three years. During that time, don Pedro went into exile with his wife, Margarita Cardenal, in New York, where they worked in different trades to support themselves economically.

“The martyr of public freedoms”

Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal had a feeling he was going to be killed. He put it in writing three years earlier, on February 13, 1975. On a typed sheet of paper he read the warning that he could be eliminated by Somocismo. Chamorro Cardenal said that a source was present at a meeting in which there was talk of kidnapping him and taking him to the Air Force, and then throwing him out of a plane into the sea.

Unlike his father, Chamorro Cardenal declared himself an anti-Somocista. When he took over the reins of the newspaper in 1948, he made a series of changes in form and substance that, over time, resulted in the economic success of La Prensa and its weight of influence in the country. From the pages of this newspaper, he confronted the Somoza dictatorship through his editorials, but also with notes, reports and rigorous journalistic investigations on the corruption of the Somoza regime.

The researcher and journalism professor, Guillermo Rothschuh Villanueva, in the book El Periodista, wrote that Chamorro’s journalistic practice can only be understood “in light of his commitment to the decapitation of the Somoza dictatorship”. For Chamorro Cardenal, the main challenge for Nicaragua at that time was, in the first place, “to free itself from the Somozas, since they were the first obstacle to the dignification of Nicaragua and Nicaraguans”. His reason was simple to explain: the Somozas were the main barrier to aspire to live in a country with freedom of expression, that is, to live in democracy.

During his 30 years at the head of La Prensa, Chamorro Cardenal was imprisoned on at least five occasions by the Somoza dictatorship. The first of these was due to his participation in a frustrated plot against Somoza García in April 1954. Pedro Joaquín was sentenced to two years in prison in a war council. Two years after his release, he was imprisoned again, like thousands of other Nicaraguans, after the assassination of the dictator, Anastasio Somoza García, even though he did not participate in the attack.

On that second occasion, Chamorro Cardenal was tortured in La Loma prison, where the former Judicial Assistance Directorate (DAJ), El Chipote (old), was located. His entire experience is narrated in his book Estirpe Sangrienta (Bloody Strain). He was again convicted and confined to his home in San Carlos, Rio San Juan. However, he escaped with his wife, Violeta Barrios, to Costa Rica, where they both requested asylum. He suffered the rest of his imprisonment in 1959, during an attempted armed rebellion to overthrow Somoza, known as “Olama y Mollejones”. On that occasion, he was sentenced along with other comrades and friends to 11 years in prison. But he was released a year later through an amnesty. That year he returned to direct La Prensa.

Chamorro Cardenal was imprisoned on a couple of other occasions. Legal proceedings were opened against him for his editorials or news published in La Prensa. After the Sandinista raid on the house of “Chema Castillo”, an operation that freed several guerrillas, among them Daniel Ortega, the dictator, Somoza Debayle, censored La Prensa for 33 months.

Pedro Joaquín Chamorro suffered all this until his assassination in January 1978.

Ortega-Murillo against the Chamorro

On August 12, 2021, the newspaper La Prensa published that it would no longer circulate in its paper edition because the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo had blocked its raw materials. “The dictatorship retains our paper, but cannot hide the truth,” they headlined. The following day, the Police took by force the newspaper’s facilities, and imprisoned the secretary of its Board of Directors, Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro.

From that day on, Holmann Chamorro was transferred to the Dirección de Auxilio Judicial (DAJ), where he was locked up, under torture conditions, for a year and seven months. He was exiled along with 222 other political prisoners to the United States. The Ortega and Murillo dictatorship also ordered the removal of his nationality and the confiscation of his assets in Nicaragua.

The Ortega-Murillo takeover of La Prensa occurred just 13 days after its last director, Jaime Chamorro Cardenal, died at the age of 86. “We greet all that family and express to them that we are always in prayer for those brothers and sisters or for those people who even thinking differently we are able to unite in humanity and fraternity with and above all to raise prayers to the most high so that we meet (sic) and we are all travelers to that other life,” said Rosario Murillo, as condolences. Murillo was Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal’s secretary and, therefore, knew Jaime, Pedro Joaquín’s brother, well.

Juan Lorenzo Holmann became the most visible face of the Chamorro family after the death of Jaime Chamorro Cardenal. Months before, the regime imprisoned Cristiana Chamorro Barrios, vice-president of the Board of Directors of La Prensa, for showing intentions to be a presidential candidate. For the same reason, they arrested her brother, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Barrios, also an executive of La Prensa. Another brother, Carlos Fernando Chamorro, was forced into exile after his offices, where he directed the newspaper Confidencial and the television program Esta Semana, and his house were raided without a legal warrant.

A year later, the entire editorial staff of La Prensa moved to Costa Rica, after two drivers were captured and a news team was chased. Nicaragua became the only country in the Western Hemisphere that has no print newspapers, according to a check conducted by the Inter American Press Association (IAPA) in early 2020, when this same Nicaraguan newspaper suffered a 75-week hold that almost led to its total closure.

“Even in failed states such as Syria, Somalia and South Sudan there are print newspapers,” the report notes.