Maria Esperanza Sanchez dreams every day that she is in Nicaragua. “If they had given me the choice between being released but banished to the United States or staying in prison, I would have stayed in prison,” she says via phone call from Houston, Texas, the city where she lives. There are many reasons to think this way, but what weighs most heavily on her is to sustain a life in a country that is very foreign to her. A language different from her own, lack of employment and opportunities, and poor health are the main challenges she, and other political prisoners her age, face after nearly seven months of a banishment imposed by the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship.

This 55-year-old woman feels that many have been forgotten, that after February 9, when the dictatorship sent more than 222 political prisoners to the United States nobody remembers them anymore. After her release, the multiple interviews she gave to the media and the adrenaline of being in a strange and forced “freedom” far from her origins, the weight of the routine and the responsibilities of the day mark Maria Esperanza’s life.

“The economic part is the most difficult,” she says. Making ends meet to pay rent for a $1,040 room is, at times, an odyssey. The place she got for herself was thanks to solidarity networks that were established after the arrival of the released prisoners in the United States. If this had not been the case, it would have been impossible to obtain housing, because, as Maria Esperanza explains, for everything you need a credit record, and that is achieved by starting to work.

The Nicaraguan diaspora in the United States handled everything related to housing for most of the 222 political prisoners exiled by the dictatorship. “What we did was that a group of people and organizations of the diaspora opened the doors of their homes, for a period of three months. It is very difficult, because the diaspora was not emotionally prepared to receive them,” remarked Damaris Rostrán, a Nicaraguan activist based in the United States since 2022, who dedicated herself to coordinating solidarity networks for the political exiles.

Thanks to this solidarity among Nicaraguans themselves, Maria Esperanza has managed to get a small job. Her main source of income is a job with an organization made up of Latinos who look out for the interests of the community in which she lives. It consists of conducting surveys. The pay is about $20 an hour. She’s just getting started, and she’s excited about it. She was lucky to find it, because she had no idea how she was going to pay her month’s rent. Last month she received help from an organization with which she was able to cover the expense. But help doesn’t come every month.

The aftermath of imprisonment

Maria Esperanza still has sequels of all the time she spent in prison. She was captured on January 26, 2020. The dictatorship convicted her for drug trafficking, a crime used by the Prosecutor’s Office to mask the cases of political prisoners. All this was before the approval of the Law for the Defense of the Rights of the People, a norm that criminalized “treason to the homeland”.

During all the time she spent in the women’s prison “La Esperanza” she made small acts of resistance that “kept her spirit alive”. One of them consisted of painting her nails blue and white – the colors of the Nicaraguan flag – to show that she was still committed to the cause that led her to become a political prisoner. But the after-effects of poor diet and prison conditions have taken their toll on her physical health.

She and 221 other political prisoners were sent to Washington on the morning of February 9. It was an agreement made between the dictatorship and the State Department, through the U.S. Embassy in Managua. That early morning, Maria Esperanza recalls that they took her out of her cell, along with other political prisoners, without telling them that they would be taking a one-way flight. “We still, at least in my case, had a lot of faith that I was going to see my family, that I was going to see my daughter, who is in the hospital,” she adds.

She recalls seeing the plane with other prisoners and her first impulse was to cry. “That moment was hard. At least in my case, three years and 15 days in a prison where I only saw my two daughters very occasionally, and my son because of the danger of seeing me,” she says, still emotionally affected by the memory.

When they arrived, U.S. officials, a handful of Nicaraguans from the diaspora and total uncertainty awaited them. They arrived in the country under humanitarian parole, a measure that, according to Damaris, does not represent a public charge. “It is a strong term, but it is the one used. You cannot be a burden to the State with parole. When you come as a refugee to the United States, you have access to other conditions, such as housing for a period of time, health insurance, and English language schools. In other words, you go through a process of insertion,” she adds. In spite of this, she estimates that 98% of the exiles have a work permit. The challenge lies in finding a job.

After her arrival in the United States, Maria Esperanza’s asthma worsened and she was diagnosed with cardiovascular and blood pressure problems. ” About two months ago I had an ultrasound, an ultrasound that I requested to see at the prison and the warden never allowed it, and I had it done here again. It showed that the lymph gland was larger than normal. There are times when I speak well, but there are times when it is swollen and I have shortness of breath. The specialist says I have to have surgery because I have blood clots,” she says.

She does not know how much the operation will cost, but she does know that it is not cheap. She fears that she does not have enough money to pay for it and that the private insurance she chose will not cover it. More tests are still needed to be sure about the operation.

The days go by and all Maria Esperanza wants is for her health to improve. She has almost no time left to think about her activism, to meet with the groups abroad that intend to stand up to Ortega and Murillo who, based on repression, have strengthened themselves to unsuspected limits. In the new country where she lives, work and personal problems consume all her time.

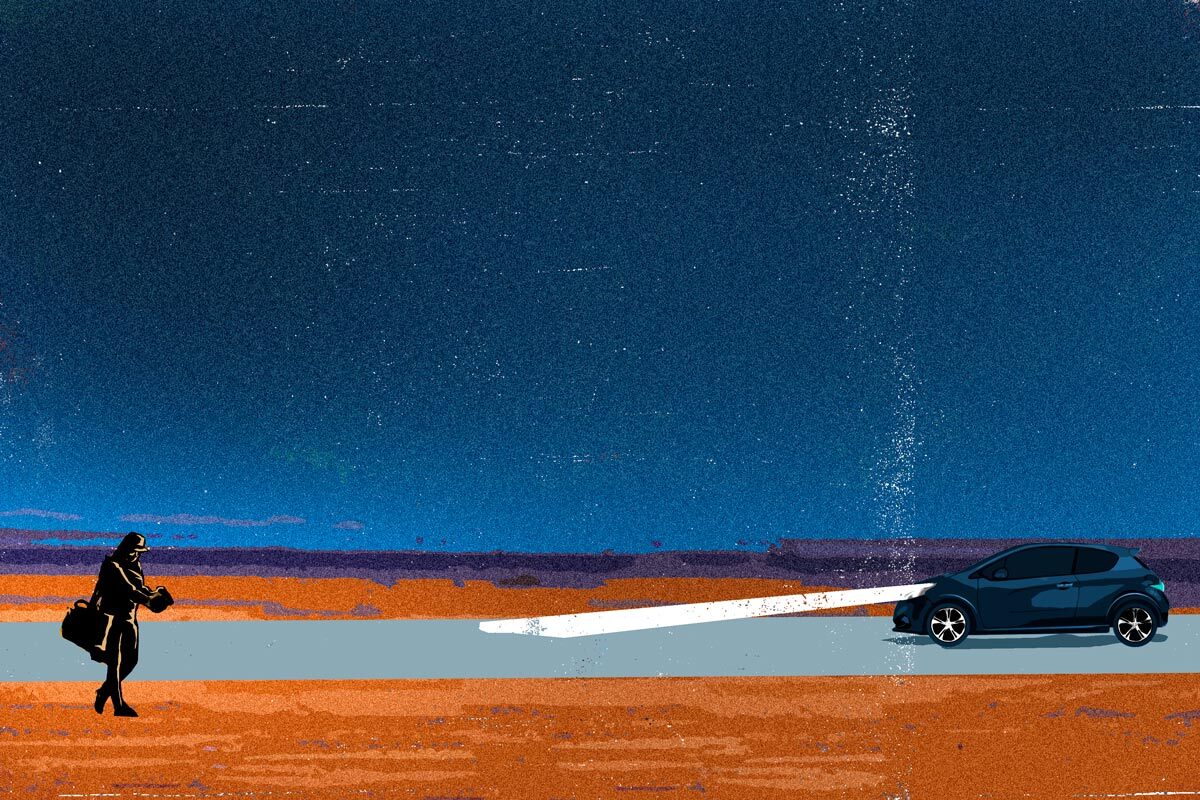

“It’s freedom, but at the same time I feel like a prisoner because I can’t move. The distances, the places… everything is so far away,” she reflects.

Released from prison, but afraid

Javier*, 54, is afraid even though he is thousands of miles away from his tormentors. He fears not for himself, but for those who remain in a Nicaragua whose repression has extended to the families and friends of political prisoners. He agrees to this interview on the sole condition that his name and any identifying details that could endanger his wife and children who remain in the country, and with whom he hopes to be reunited, are not mentioned.

Javier lives with his son – who has been living in Texas since 2021 – in a two-bedroom, one-bathroom trailer for which he pays $1,000 a month. He is originally from Chinandega, a department where he has lived accustomed to life in the countryside. As a result, most of the jobs he has gotten after his banishment on February 9, 2023 consist of trimming trees or mowing lawns.

It’s nothing permanent. Sometimes he gets called every other day, once a week, and if lucky, three times. Also the hours and pay vary a lot. Occasionally it’s $90 a day, $100, $110. It depends on who he works for. On top of rent, he adds $70 for a phone line and food, and he barely has enough left over to treat himself.

His son works at a car wash, where the pay is usually no more than $11 an hour. These are the kinds of jobs that Latin American migrants who come to the United States in search of a better life tend to get.

Despite this strange freedom that consists of not being inside a cell, like the one he spent 14 months in, Javier is afraid and does not feel free. He suffers from anxiety, insomnia and depression. He believes these are the after-effects of imprisonment and psychological torture. And also the uncertainty of a new life that is just beginning to take shape.

“So far it has not been possible for me to adapt much to the place, because the culture is very different from ours. And when it comes to work, here you have to have a car for everything. Sometimes you can get a regular job, but it is in an area that is half an hour away by car. An Uber charges you 20 or 30 dollars, so you can’t afford to accept it,” he says via telephone.

Despite the time and the fact that life requires him to get into a routine to survive, he still spends hours thinking about Nicaragua, about his detention, about the months of imprisonment. On November 6, 2021, two police officers came to his house to ask for him. Then the whole house was surrounded by police. He was taken to prison and was prosecuted for cybercrimes and propagation of false news, one of the repressive laws that the dictatorship has used to imprison its critics.

In all those months he was subjected to a series of interrogations in which he was questioned about why he published things against the regime. Some of these publications served as “evidence” in his trial.

However, there is one idea that still keeps him hopeful. He has heard that in a country like the United States, sometimes the best thing to do is to be an entrepreneur. That’s why he wants to start a Nicaraguan restaurant. It is a dream that makes him think that he will be able to improve his economic situation and get ahead. “I want to do it when my wife can be with me. I hope that soon we can be together,” he says.