The Ministry of Health (Minsa) changed the term used to identify minors with symptoms of acute malnutrition, according to the latest statements regarding the progress of the National Plan for Monitoring the Nutritional Status of Children aged 0 to 6 years.

Until November 13, 2023, Minsa explicitly referred to these children as “identified with acute malnutrition” in its statements. However, after the release of a special report by DIVERGENTES on this issue, Minsa changed this information to “attention to children to monitor and improve their nutritional status”.

This change was not only applied to new statements but to all previous ones since July 2023. Prior to the November 13 statement, Minsa reported 117,912 “children identified with acute malnutrition”; now it indicates that there were 117,912 “attentions to children to monitor and improve their nutritional status”.

From July 9, 2023, to February 3, 2024, 177,469 children under 6 years old have received attention “to monitor and improve their nutritional status,” according to Minsa and their new way of referring to acute child malnutrition.

Now there are no ‘malnourished’ children, but children ‘attended to’

This change in nomenclature is a “euphemism” to “disguise” child malnutrition data, which violates Minsa’s state and international commitment to providing accurate health statistics, says public health expert Ana Quirós. “Minsa has an obligation to present this data in a truthful and verifiable way. For this, they have the support and resources from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), UNICEF, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). However, the professional character of the Ministry of Health, adhering to international standards, has diminished,” she explains.

According to the specialist, this change aims to present a narrative in which there are no “malnourished” children, but “attended or improving” children.

“With this change, they want to hide what is really happening. They want to show that they are being effective, when we cannot know if their nutritional situation has not only improved but clearly could have worsened because the purchasing power of the Nicaraguan population is clearly decreasing,” she adds.

Their goal is to hide child malnutrition

A sociologist and data analyst who requested anonymity points out that Minsa must adhere to international terms and health categories regarding epidemiological information. That is, Minsa has the obligation to call malnutrition as such and not to label it otherwise.

“Not using the required terms is a point of alert because it risks invisibilizing, hiding, and using euphemisms to hide child malnutrition data. The number of those attended says nothing, it does not say what clinical situations they attended to, nor what methodologies they used to define their nutritional status,” he says.

According to the sociologist, it is dangerous for Minsa to use this type of ambiguity because it is from these statistics that the state plans to address the needs of the population. “If you have a malnutrition problem at hand, it is because there is also a problem with food security and poverty, but that cannot be addressed if that type of data is not properly presented,” he explains.

Quirós also points out that child malnutrition data is one of the most important health data in a country because it is an indicator of the general health situation, especially of children.

“It is important data because children with malnutrition from early childhood already have symptoms in terms of their physical, mental, and cognitive development. And if that is not addressed, future generations are doomed to a deficit in development and to a lower intellectual capacity than they could have had,” she explains.

This is not the first time Minsa manipulates information

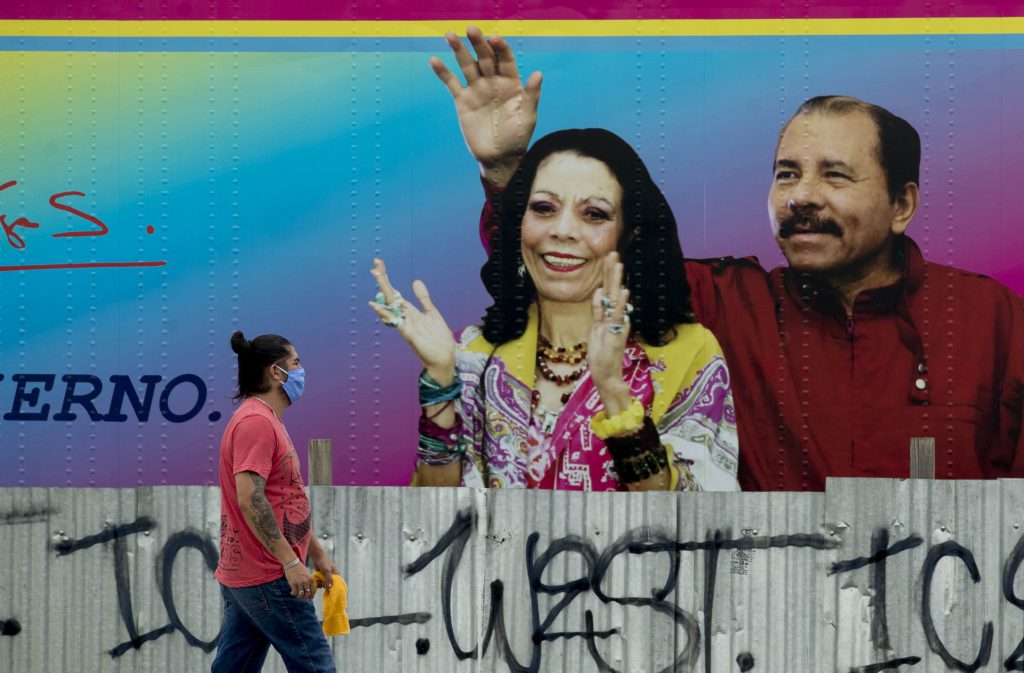

Quirós indicated that it is not the first time that Minsa uses euphemisms and manipulations to manage the country’s health data but is part of a policy historically kept by the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship, which has intensified since the socio-political crisis.

The last situation in which the manipulation of data by Minsa was evidenced was during the coronavirus pandemic when infected people were not classified as coronavirus patients but as pneumonia or other respiratory diseases, recalls the sociologist and data analyst. “The last time it happened was during the Covid-19 pandemic. Covid statistics were the great unveiling of the manipulation of statistics and in this case of public health. They only classified it as a respiratory disease, although it is true that it is, in terms of a pandemic, it was not in line,” she explains.

Minsa is not the only institution disguising health information

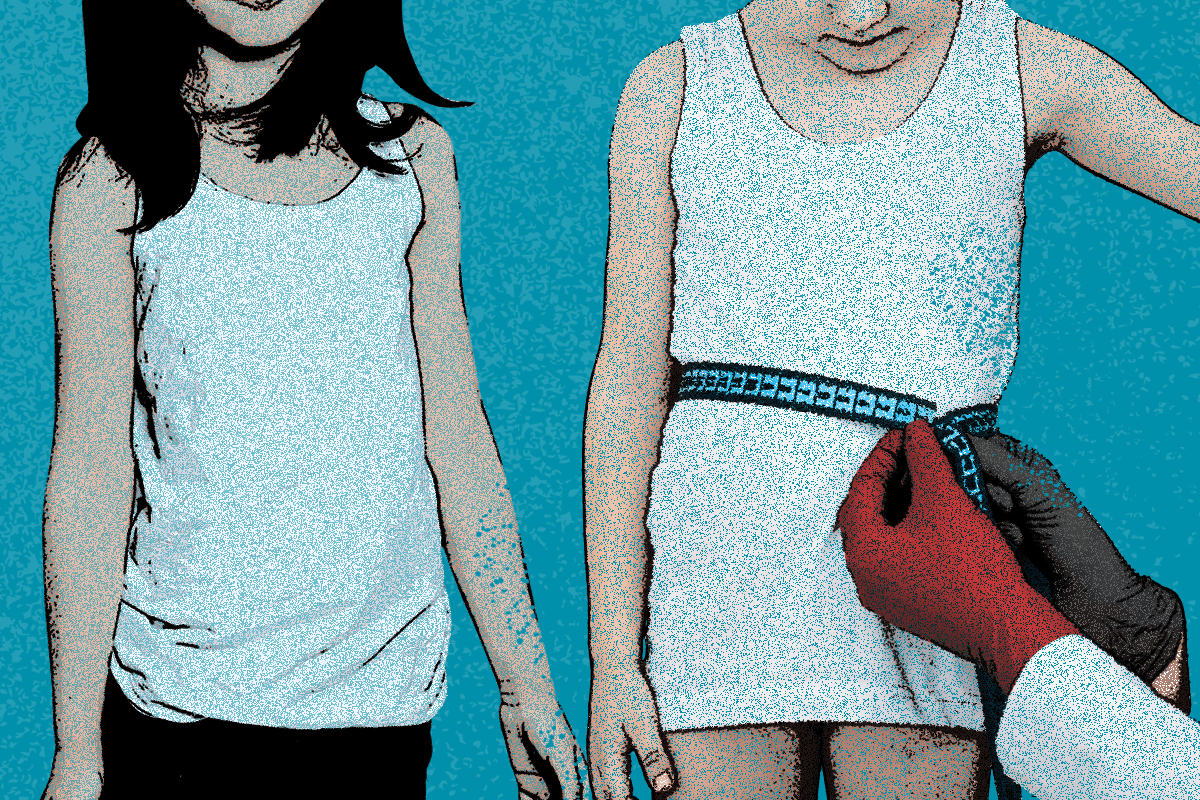

Another institution that made a change in the way data is read was the National Institute of Development Information (INIDE), in the Vital Statistics Compendium on the ages of women giving birth.

Minsa had already made this change years ago, by ceasing to disseminate by years the ages of girls and teenagers who become mothers and placing them within a single category as “under 20 years old.” INIDE was the only institution where it was possible to specifically know how many girls between 10 and 14 years old, as well as teenagers between 15 and 19 years old give birth every year in Nicaragua.

Although the five-year division of ages still exists, INIDE changed the category of girls between 10 and 14 years old to “under 15 years old.” According to feminist activists, this is also a way to hide the serious problem of child pregnancies and sexual violence.

“They do not want to admit that there are girls aged 10, 11, or 12 giving birth; they prefer we read the 15 year old category and think they are teenagers, but not to know that these are children giving birth,” they explain.

According to the latest report from the Vital Statistics Compendium 2021-2022 by INIDE, at least 27,098 teenagers and girls became mothers, representing 22.3% of this segment throughout the country.