They disappeared from political life

For this article we sought the versions of the other presidential aspirants imprisoned by the dictatorship: Noel Vidaurre, Medardo Mairena, Miguel Mora, Arturo Cruz and Cristiana Chamorro - to know how they were a year after their exile - but we only got the testimonies of Juan Sebastián Chamorro and Félix Maradiaga.

They and Medardo Mairena are the only ones who remain active - at least publicly - in political platforms and international advocacy to denounce the human rights violations committed by the Ortega-Murillo regime in Nicaragua.

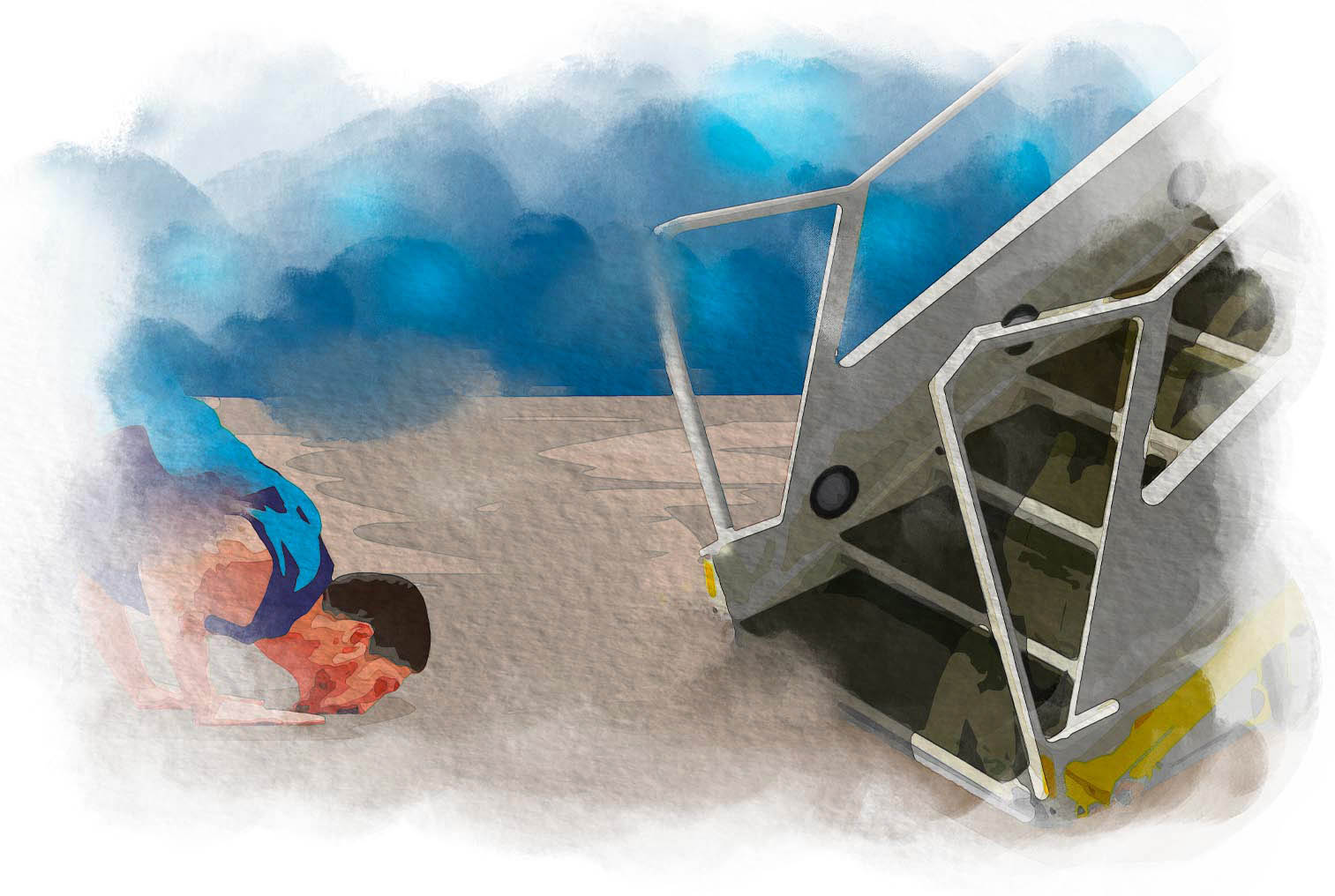

During the 611 days that Juan Sebastian was in El Chipote, he was one of the few political prisoners who did not receive visits from his closest family members. This was because his wife, Victoria Cardenas, was accused of "treason" in retaliation for a global human rights campaign she carried out, together with Berta Valle - Felix Maradiaga's wife - to denounce the situation of political prisoners in Nicaragua; while his daughter, Victoria Chamorro traveled to the United States to study at the University of Notre Dame, where Juan Sebastian is now a professor.

When the guards came to his cell on the night of February 8, 2023, Juan Sebastian had not seen his wife and daughter for more than two years. He shared the space with Roger Reyes, another political prisoner, with whom he chatted every night until they fell asleep or got bored.

But that night, when the guards handed them their clothes so they could change out of the blue " jumpsuit" they wore in prison, they both thought the worst was in store for them.