Nydia Elisa Monterrey Guillén, a Nicaraguan migrant, was dealing with severe abdominal pain and a high fever when she went to the Adolfo Carit Eva Women’s Hospital in San José. It was 2019, and she had just arrived in Costa Rica after fleeing Nicaragua due to the persecution unleashed by the Sandinista dictatorship because of her work as an independent journalist.

In addition to her severe health issues, Nydia endured a nightmare trying to access medical care in Costa Rica. Although she had refugee-seeker status, her request for treatment was denied.

“They told me they only treated minors or pregnant women without insurance. I asked for a written explanation for the denial, but they refused, claiming it wasn’t a rejection, just a payment condition,” she recalls.

Despite these hurdles, Nydia, then 25, managed to scrape together the money for her appointment, but she faced another obstacle when presenting her identification. “The official told me my document wasn’t valid, that it was like carrying a driver’s license. Even though I paid, I felt like an undocumented person,” she says.

After receiving medical attention, she was diagnosed with a severe kidney infection and admitted to the hospital. The financial uncertainty weighed on her during her six-day hospitalization, racking up a $6,000 debt, until an unexpected pregnancy diagnosis led to coverage.

“Just because I was pregnant, they covered my expenses—not because of my rights as a person. It’s not the woman that matters, it’s the Costa Rican citizen that’s about to be born,” she laments. After giving birth, the government insurance she received only covered the 40-day postpartum period. The lack of support and bureaucratic hurdles made it difficult for the father of her child to insure her, leaving her once again reliant on expensive private systems.

Marianella Gómez is another Nicaraguan migrant who experienced poor healthcare treatment within Costa Rica’s public system. Two months after arriving in the country as a refugee applicant with her two children, aged 7 and 15, in May 2024, Gómez went with her eldest son to a health clinic in the San José neighborhood of Alajuela. There, she encountered an official who questioned why she wasn’t enrolled in the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS).

“My son needed urgent care, and the official insisted he wasn’t insured, until I told her I was there because I knew of a law that guarantees free healthcare for minors. Even then, she told me the care belonged in another health unit, but the security guard stopped me on my way out and redirected me to the Emergency line, where I was finally seen,” Gómez recounts.

The Nicaraguan migrant community, which is the largest in Costa Rica with over half a million people, faces the greatest challenges in overcoming the barriers to accessing healthcare services.

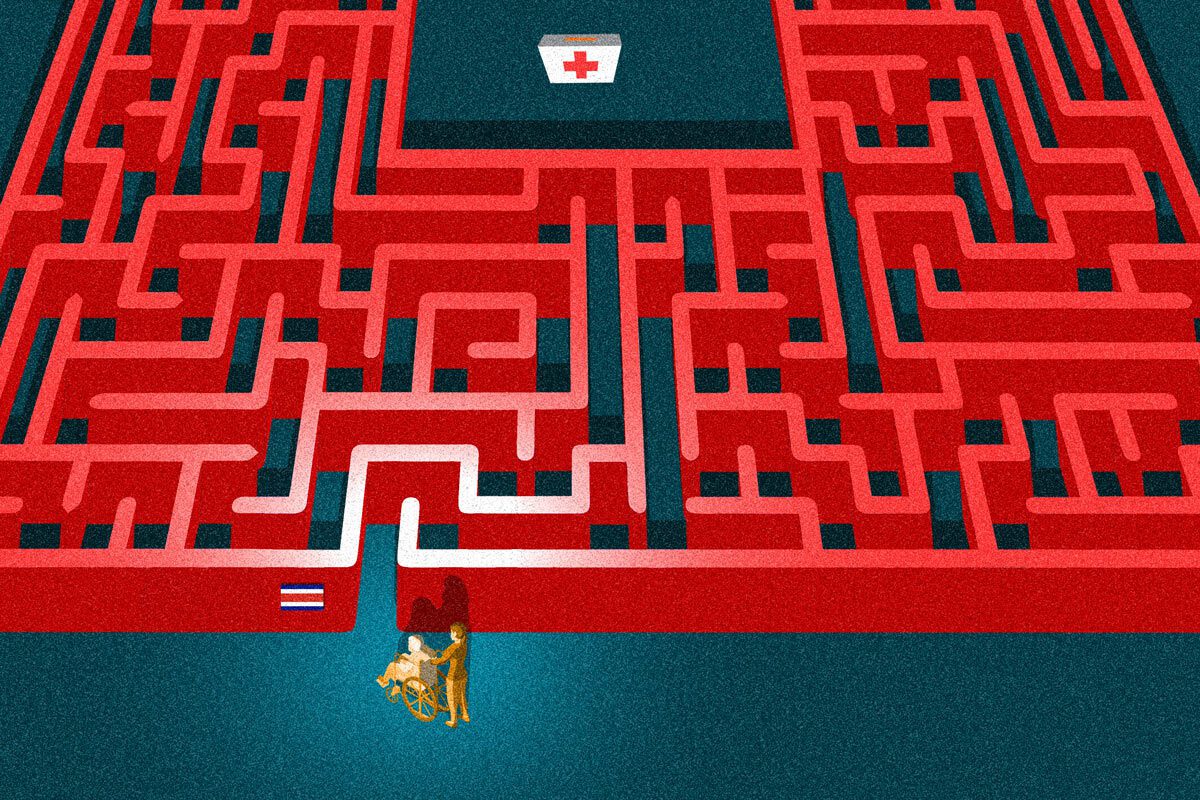

Bureaucracy, Ignorance, and

: The Main Obstacles

The government of Costa Rica has implemented policies to facilitate migrant access to public healthcare services. However, according to testimonies and specialized studies reviewed by DIVERGENTES, bureaucracy, ignorance among state employees, and xenophobia remain persistent issues in healthcare centers.

The Costa Rican healthcare system is structured in a primary level consisting of Basic Comprehensive Health Care Teams (EBAIS), a secondary level that includes peripheral clinics and regional hospitals, and a tertiary level, which is made up of national hospitals.

Primary care is provided in the EBAIS, which are assigned based on residents’ addresses. There are 1,104 of these units across Costa Rica. Depending on the severity of the medical issue, patients are referred to secondary or tertiary care.

The Costa Rican healthcare system is not entirely free. If a patient is not registered with the CCSS and receives care within the public health system, they must pay for the medical services later. However, Costa Rican law outlines specific situations in which healthcare services are free, such as for pregnant women and minors, which also applies to migrants.

Since 2018, Costa Rica’s Constitutional Chamber ruled that the Directorate General of Migration and Immigration (DGME) must provide a temporary document that allows migrants to begin the process of registering and obtaining insurance with the CCSS.

Reports of Abuse and Negligence Toward Migrants

Maricela Hinkelammert Palma, advocacy officer at the Migrant Social Rights Center (Cenderos), told DIVERGENTES that many Nicaraguan migrants report abuse and neglect at centers like EBAIS and hospitals in areas such as Upala or San José. However, it is common in this population not to take these complaints to the relevant authorities.

“If people aren’t organized or haven’t reached out to a social organization that advocates for migrants’ rights, they don’t recognize their rights in the host country. We find that people are influenced by others’ comments or by the experiences they’ve heard about,” she explains.

“There’s a fear of approaching health centers because they know that if they don’t have insurance, they won’t be treated or will be charged amounts they can’t afford. However, there are exceptions, such as care for minors and pregnant women, which is covered by the state,” the social activist emphasizes.

Breaking Barriers Through Community Monitoring

To combat these barriers, Cenderos has developed initiatives like community monitoring and the training of local promoters. These training sessions, led by women, play a crucial role in informing their communities about their rights and collecting testimonies of violations, making abuses visible and encouraging changes in healthcare services for the migrant population in Costa Rica.

This approach strengthens Nicaraguan migrant communities and creates support networks that are essential in overcoming the barriers imposed by the system.

“There is discriminatory treatment in the EBAIS where we receive the most complaints. These complaints are concentrated in healthcare centers located in cantons with large migrant populations, and the reasons for denial of care are unjustified,” Hinkelammert points out.

“Several examples involve women who arrive with sick children. If they aren’t insured, they won’t be treated, and they’re not informed of the process they need to follow to be covered by the state. Then, when it’s time for vaccination checkups, they scold the women and threaten them with intervention by PANI (Costa Rica’s National Child Welfare Agency) for negligence. It’s hostile treatment, with no interest in providing information, especially to low-income Nicaraguan families,” the Cenderos representative denounced.

CCSS: We Are Constantly Training Staff

DIVERGENTES requested an official stance from the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS) regarding public policies for healthcare services for the migrant population. The responses were partial, with the institution highlighting its ongoing training efforts regarding migrant care.

“From the institution’s perspective, we carry out communication and awareness campaigns about the various types of insurance coverage. We use various media, including the website, social media, and other mass communication channels. Internally, we constantly provide training and advice to employees who interact with the user population,” stated a press department email from the CCSS.

“According to the Children and Adolescents Code and Law 7735 on the Protection of Adolescent Mothers, pregnant women and minors are protected by the state if they are not covered by other insurance regimes. If a specific case is identified, it should be reported so that the appropriate authorities can conduct the necessary investigations,” the statement added.

The entity defended that any medical charges are applied when the patient’s situation warrants it, in accordance with CCSS procedures.

“Charges for medical care are applied when an individual is required to contribute to the system but is overdue, or if the individual does not qualify for state insurance, Family Protection, or any special law that covers them. In this case, the person is considered uninsured, and charges are applied according to the applicable regulations,” the government response clarified.

The Nicaraguan Migrant Surge Came at a Complex Time

A study called “Universal Coverage?” The Barriers to Accessing Healthcare for Nicaraguan Refugee Populations in Costa Rica, conducted by specialists Alberto Cortés Ramos and Adriana Fernández Calderón for the University of Costa Rica (UCR), analyzed the challenges Nicaraguan migrants face with Costa Rica’s healthcare system.

The study primarily highlights that the migration wave of Nicaraguans, driven by the economic collapse and the repressive police state imposed by the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship, seeks to access Costa Rican healthcare services amid “transformations in social security that have translated into budget cuts, deteriorating service quality, a decline in the universalist project, as well as institutionalized ‘xenophobia.’”

“There are cases where individuals previously sought healthcare services, but without insurance at the time, they end up with unpaid bills. Even when they try to obtain insurance, they can’t, which impacts their ability to renew their documents. These are stricter measures imposed by public institutions that prevent access to services, as in the past, migrants could secure insurance with fewer requirements,” the study notes.

Since June 2018, Costa Rica has had the directive 010-MP MIDEPLAN-MTSS-MSP-MGP-MRREE, issued by the Ministry of the Presidency, along with other ministries, which sets out guidelines for addressing migration flows entering or remaining in the country under “special or exceptional situations, such as transit, irregular status, asylum, trafficking of migrants, or human trafficking.”

The regulation establishes that the migrant population is entitled to basic healthcare for illnesses and conditions according to the existing legal framework, and that the state will cover the cost of such care.

Healthcare system officials must verify that individuals have insurance. In the case of pregnant women and minors, a bill can be generated at the state’s expense. For others, if they are uninsured, a bill is generated in their name.

Funding Alternatives for Medical Care

These medical services can be financed through the Special Migration Fund, the Migrant Social Fund, and the National Fund Against Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling.

Adult migrants without the ability to pay for healthcare services can channel their bills to the Unit for Validation and Medical Services. Identification can be provided through a passport or a document or card issued by the National Migration and Immigration Department.

“The migrant population can access the first level of care without any insurance; however, from the second and third levels onwards, in the absence of certain insurance modalities, they are required to pay for the services received. In practice, many times officials are unaware of these provisions and deny access to services in the EBAIS. As a result, treatable conditions or those that could have been diagnosed in time become more complex and harder to treat,” the University of Costa Rica’s (UCR) study highlights.

The Key Lies in Public Officials’ Knowledge

The correct path to accessing healthcare services is extremely complicated, and the adequacy of access depends on the officials’ knowledge of the various guidelines. This directly impacts whether the migrant population is properly informed about the steps they must take to access these services.

Organizations interviewed for the UCR report note that the standardized issue of a lack of information regarding the billing process often discourages migrants from seeking treatment for ailments, fearing debts they know they may not be able to pay.

“Many officials say, ‘Well, we can give you the appointment, but it will be billed in your name,’ and then people leave because they don’t know the amount. But in reality, the charge is not for the person; the official just needs to generate a number using the person’s information, but ultimately, the bill will be sent to the state,” the UCR report explains.

The population repeatedly mentioned that the CCSS is one of the institutions where they have experienced the most discrimination and mistreatment, aligning with reports from the Cenderos organization.

“They report that there is ‘institutionalized xenophobia’ permeating all levels of the institution. They have been denied care because of aporophobia towards Nicaraguans, which is expressed in the derogatory way they are treated, the disrespectful behavior when they make inquiries, and the repeated times they are denied access to services,” the study noted, according to focus groups conducted for its creation.

Challenges in Costa Rica’s Healthcare System

The study concludes that, despite Costa Rica’s tradition of solidarity and aspirations for universal healthcare coverage, there are many institutional barriers preventing the migrant population from accessing healthcare services.

“The new guidelines and circulars for addressing the Nicaraguan population that began arriving in April 2018 create pathways to healthcare services. However, in practice, these pathways are blocked by misinformation among officials, frequent regulatory changes, vague language, and cumbersome procedures for completing access processes, along with significant levels of institutionalized xenophobia,” the study emphasizes.

“Moreover, there is evidence of a deeply ingrained culture of charging among counter staff, who seek to collect payment for all services. This weakens the practical implementation of Costa Rica’s mission for universal healthcare within social security. This issue is not limited to the migrant population, but the data suggests that the rejection is especially strong toward foreigners,” the specialized report condemns.

ACNUR and CCSS Initiative

Since 2020, the UN Refugee Agency (ACNUR) and the CCSS have had an initiative to cover healthcare for a set number of refugees who cannot afford health services under the available insurance schemes in Costa Rica.

Between 2023 and 2024, 5,000 people are insured under this agreement, including asylum seekers, refugees, those at risk of statelessness, and stateless individuals in economic and health vulnerability. The vast majority, 4,459, are Nicaraguan.

A report from the digital platform Confidencial explained that asylum seekers who wish to apply for coverage under this agreement must fill out a medical data form. Applications are processed by ACNUR based on the priority of their medical condition, according to the information provided by the applicant, who must prove that they cannot afford insurance on their own, as per the guidelines of the agreement.

Applicants are placed on a waiting list, and as cases are resolved and spaces become available, selected individuals will be contacted by ACNUR to inform them of the approved benefit.

They will then receive an identification card that they can present to access all Costa Rican public healthcare services. However, the waiting lists depend on available spaces, which are subject to change due to the entry and exit of beneficiaries.

It’s been nearly five years since Nydia faced a health crisis that nearly led to both financial and mental collapse. She now runs her own business, a well-known Nicaraguan food site called La Gigantona, and has fully immersed herself in Costa Rican life. But she doesn’t forget that her story is just one of many that migrants, especially Nicaraguans, endure and suffer.

“They might tell you that Costa Rica’s doors are open to migrants and asylum seekers, but that’s the romanticized version seen in the media and perhaps to the international eye. But the reality is quite different,” she reflects.

This report is part of the Workshop and Master Classes project by DIVERGENTES with support from Germany’s Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the German Embassy in Costa Rica.