Surveillance initially occurred during the nights and early mornings. Then, the monitoring became more intense: private vehicles and motorbikes parked during the day outside the offices of the Nicaraguan Collective of Human Rights “Nicaragua Nunca Más,” located in San José, Costa Rica, specifically in the San Pedro area. This neighborhood is close to the University of Costa Rica (UCR), businesses, and bars, yet it is also a quiet residential area where neighbors often recognize those who frequent their blocks. So, those cars, those motorcycles—even those men who repeatedly went through the human rights defenders’ trash—were strangers. They had no connection to the residents of La Granja neighborhood. Thus, suspicion arose joined by caution.

The risk became unavoidable when one of the lawyers received a direct death threat. They were warned that they were “on a list.” This happened days after the opposition figure Joao Maldonado was shot for the second time in the San Pedro area, very close to the offices of the human rights defenders… Urgent action was needed.

“There was a lot of surveillance, and we had to change offices to a safer space. The risks were high because they (the Government) want to get rid of any possibility of justice. And how do they achieve that? By eliminating human rights defenders who are documenting the repression,” says Juan Carlos Arce, a member of the Nicaraguan Collective of Human Rights “Nicaragua Nunca Más.”

The Collective, as it is known among exiles, is a group of 16 people formed in Costa Rica after the social protests of 2018. Many of these lawyers were part of the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (Cenidh), the leading organization in Nicaragua in this field, which was shut down by the regime. Even before the closure of Cenidh, some Collective defenders had already become refugees in the Costa Rican capital. They organized and created this alternative to continue defending human rights in the context of crimes against humanity.

It was complex from the start: How to defend human rights from exile, especially considering that the regime had consolidated an intense persecution scheme that increasingly stifled the possibility of operating on the ground in Nicaragua?

Indeed, this is a question that defenders of all stripes have pondered. None have a definitive answer, whether it’s the members of the Collective, defenders of political prisoners, indigenous people, the environment, or feminists. In other words, there is no manual, and they confront complexity with diligence. There is personal, emotional, and economic strain involved.

In the case of the Collective, Juan Carlos Arce explains that the process of documenting human rights violations is “in a super complex context.” “Before, documentation involved gathering information and holding press conferences to publicly denounce. That was the traditional structure of a denunciation process. The media were allies in this action, although it’s worth noting that this was a non-formal action in defense of human rights. But all of that has completely changed. Since 2018, the space has disappeared, to the point that there is now a very strong silence.”

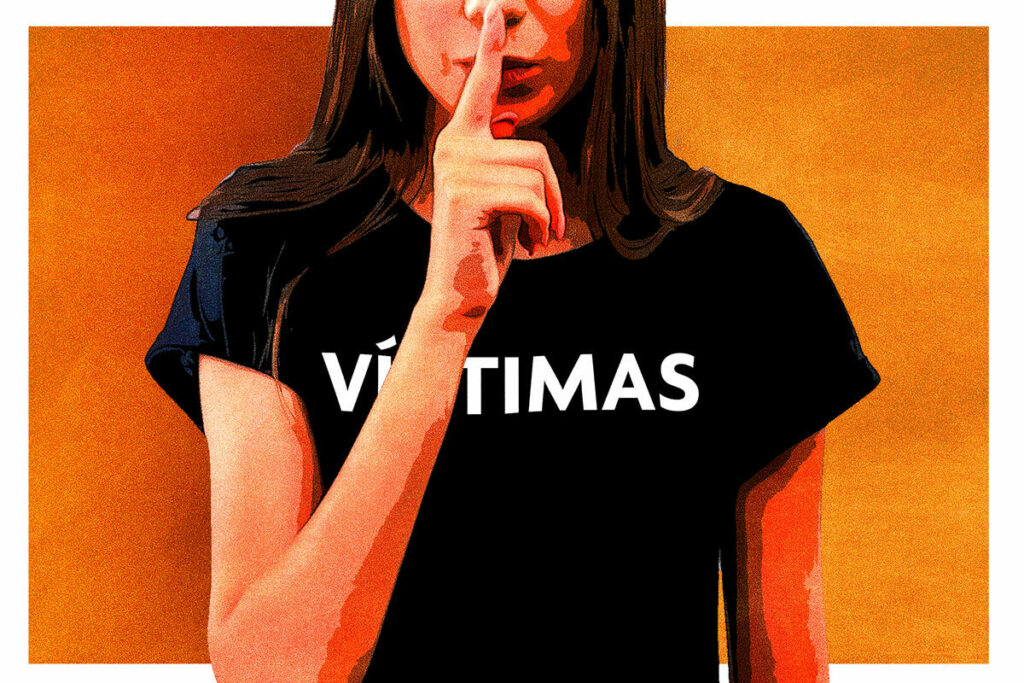

The Collective has found that victims are unwilling to speak out for fear of reprisals. Reprisals not only against them but also against their relatives abroad and within Nicaragua. Juan Carlos Arce says that “we are facing a regime that acts like a criminal structure very similar to drug trafficking.”

“People also say, I have real estate and they could go after that… against my rights like my retirement pension. There is a lot of fear, and it is paralizing,” says the Collective member. “Moreover, the regime has sent a general message that international organizations, like the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission, are useless.”

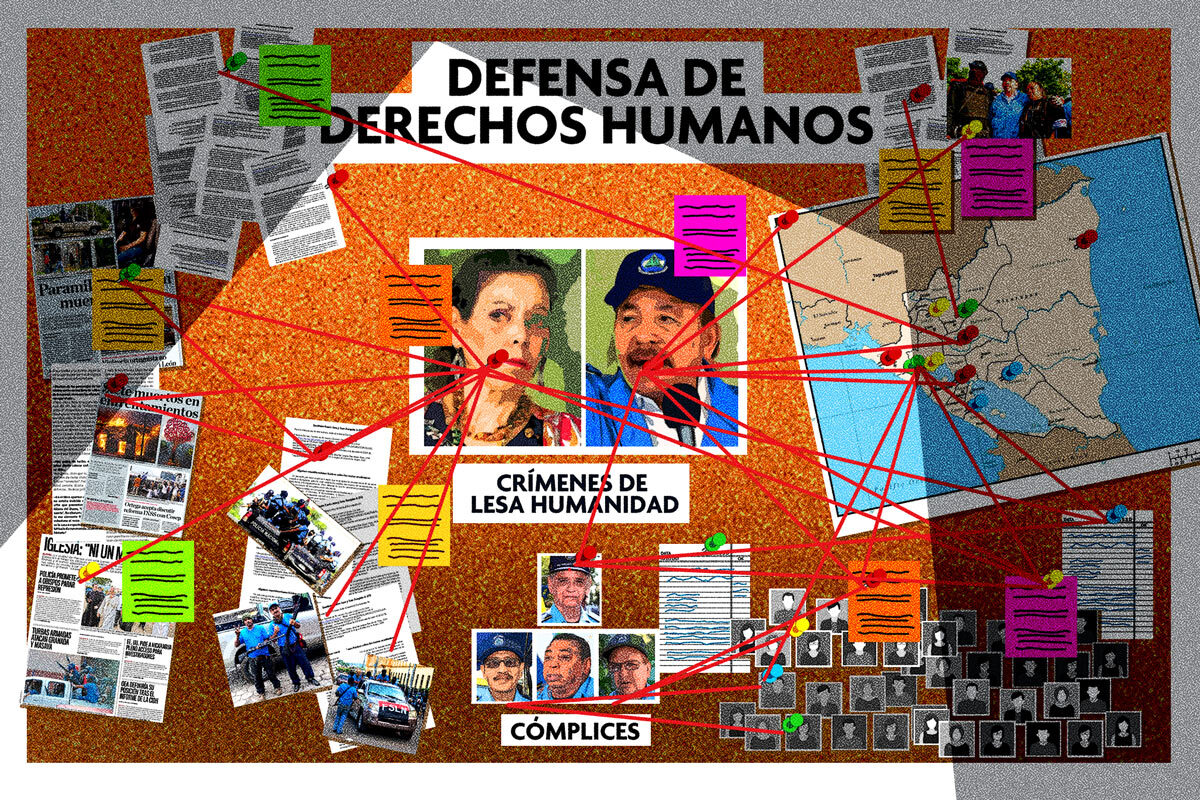

Changing the Approach: Putting a Face on Perpetrators

In what Juan Carlos Arce calls the “traditional school” of human rights—a school from which the Collective originates—there was an unchanging way of defending: giving victims a face. However, pushing this method of defense is nearly impossible today.

“Suddenly, in this context, we have to speak for the victims, but without faces. Quite the opposite of what I had learned, because the legitimacy is in the faces of the victims. Now we not only cannot show faces, but we cannot even provide a complete context for security reasons. This is frustrating. It limits your work,” laments the Collective member. “This emboldens regimes to continue violating human rights, and, on the other hand, there is an international community that is increasingly tolerant. In other words, what happens in Nicaragua has been normalized in some way. Normalizing the intolerable: crimes against humanity.”

To overcome these challenges, the Collective has “perfected” its defense method. They are constantly training to use safer methods for receiving information, mainly in digital environments. Then, they analyze the most appropriate moments to denounce. Juan Carlos Arce emphasizes that they handle the information of victims and even their own with “great caution.” “In other words, we have seen that even defenders can be victims of attacks,” says the lawyer.

However, the clearest strategy that has changed for the Collective in its defense approach is “giving faces to the perpetrators.” “If we cannot show the faces of the victims because they are targeted, then we expose the perpetrators,” suggests Juan Carlos Arce. This strategy, in exile, has brought them closer to international justice processes to eventually bring Ortega-Murillo and the followers of the presidential couple who commanded the April massacre to trial. A complex goal that, judging by other experiences, is very distant but is combined with attention to victims in the Collective’s new offices.

“Absolute Impossibility to Exercise Any Defense”

Alexandra Salazar Rosales is a lawyer who, until before 2018, operated in the corporate world. That is, she was a lawyer more used to advising companies than visiting Nicaraguan prisons, where mothers asked, crying, about the whereabouts of their children detained for political reasons by the Ortega-Murillo regime.

Alexandra’s life changed completely when she chose to put her legal knowledge at the service of political prisoners. It was not a very difficult decision, as she had been involved in organizations with social purposes since she was young. She felt that in the face of the regime’s brutal repression, there was a call she had to answer: to defend political prisoners, knowing that such defense could also lead to prison or exile… The latter happened, and since October 2021, she has lived as a refugee in San José, Costa Rica, where her life choice is evident on her bookshelves: there are no corporate codes on the shelves, but rather human rights treaties, books on the Jewish Holocaust, transitional justice papers, and stories of victims of other dictatorships.

This young jurist leads the Legal Defense Unit (UDJ), one of the few organizations fully dedicated to providing support to political prisoners and their families. The work is continuous, given the Sandinista virulence that continues to capture citizens. It’s very difficult to schedule an interview with Alexandra. Most of her time is spent in virtual meetings, assisting the families of political prisoners, or collaborating with other human rights organizations to pursue legal actions on the prisoners’ behalf. These actions may seem useless against a totalitarian dictatorship but are a fundamental requirement to demonstrate—eventually, before international bodies or the courts—that domestic processes have been exhausted, a mantra for human rights lawyers.

“Definitely in Nicaragua, there’s an absolute impossibility to exercise any kind of defense,” says Alexandra confidently, prompting the question: if it’s this impossible, what more can a lawyer defending political prisoners do? There’s much to be done, she says: “This has practically led us to provide advisory support to families regarding what actions to take, which institutions to approach to demand access to information about prisoners. Where are people arbitrarily imprisoned? And secondly, demanding some type of information from the system about the processes under which individuals are being prosecuted.”

UDJ lawyers are constantly met with denial of information by the Sandinista authorities. It’s becoming increasingly complex, but they persist. Like the Collective’s defenders, UDJ members grapple with the fear of reprisals faced by the families of political prisoners when they speak out.

“The ability to document the prisoners’ conditions, due process violations, and all the arbitrariness and nullities committed against them at the time of criminalization has been reduced,” says Alexandra. “Documentation has been limited to testimonies from family members or people in prisons. This presents other challenges because everyone is exposed. People in prisons are constantly threatened. It’s a system that prevents you from exhausting internal resources.”

The UDJ director feels somewhat frustrated because she sees her capacity for action reduced. Above all, she worries about the future: that the lack of documentation of human rights violations will have consequences in international justice and memory processes.

“We’ve already stopped being able to document specific names of all judicial secretaries, judges, penitentiary system authorities, and court authorities. Even if information emerges in one way or another, it’s incomplete,” says Alexandra. “This will pose a huge challenge when perpetrators are held accountable. So, thinking about future justice processes in international jurisdictions will be complicated because a requirement to access these instances is the exhaustion of internal resources. International organizations should understand that exhausting internal resources is impossible in Nicaragua.”

Budget Reduction

Nicaragua’s crisis reached its sixth year in April 2024. As with other longer crises—such as Cuba and Venezuela—there’s a “normalization” in sustaining these situations, especially from the international community. Human rights defenders are concerned that this normalization will impact the budgets of systems like the universal or inter-American systems.

This is compounded by Nicaragua’s location in a tumultuous, authoritarian region. However, it’s a country with a crisis relatively small on a global scale when compared to the invasion of Ukraine or the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

“The human rights setback in the region diminishes attention to what’s happening in Nicaragua. These are emergencies in contexts where the human capacity of human rights systems has been reduced,” notes the UDJ director. “This also means that there are few resolutions on Nicaragua, or that special procedures or other instances don’t pay attention to resolving all the cases that human rights organizations bring to their attention.”

Alexandra Salazar considers herself an opponent of anything that involves “normalizing the crisis in Nicaragua.” She insists on avoiding the “invisibilization of victims” and, instead, highlighting “the suffering of people inside Nicaragua, not just those in prison.”

“We need to highlight all the impact suffered by the families of political prisoners. Everything that has entailed having a person in jail: economically, socially, politically… For now, the greatest encouragement is definitely thinking that justice must come, and at that moment, we must be prepared,” says the lawyer. “Prepared with documentation: we cannot start documenting at the moment we have democracy! We have to start now because things are then forgotten. We cannot allow everything suffered in Nicaragua to be forgotten.”

Adaptation and Technology

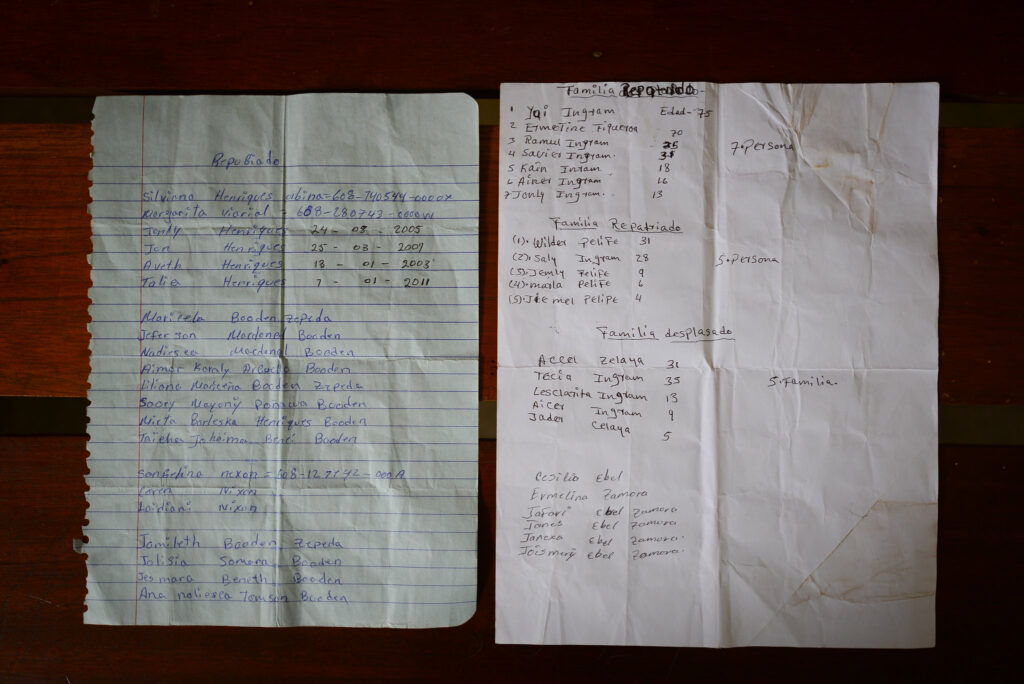

Adaptation. That’s the word that has been most challenging for members of the Prilaka organization—a group defending the rights of indigenous peoples in Nicaragua—in recent years since they went into exile. As indigenous people, the distance from their roots is more complex: they no longer live in their forests but in a chaotic city like San Jose. Hunting, fishing, and farming have been replaced by supermarkets. In the worst cases, some don’t even speak Spanish. The sense of belonging is lost in exile.

Although they try to keep their connections to the territories, especially “building trust with those who remain in Nicaragua,” distance is complex and stubborn. Nevertheless, they haven’t stopped denouncing and documenting the murder of community members by settlers who invade ancestral lands. “We’re not used to managing things remotely,” summarizes one of the Prilaka members. The man requests anonymity out of fear of reprisals. Indeed, since the Ortega-Murillo regime has intensified extraterritorial repression and asset confiscation, dozens of human rights defenders in exile prefer not to give interviews. Those who do agree also ask for anonymity for fear that their relatives in Nicaragua may be targeted.

The violence, exercised by settlers and the state, has many facets for indigenous peoples. In Prilaka, they not only identify violence that dispossesses territories but also violence against women to thwart inclusive processes.

“Distance is a very important barrier, but there are others such as team security management, continuous training and not being on the ground. The dictatorship has perfected and deepened its model of surveillance and monitoring. Also its model of co-opting professionals for its projects at the level of state institutions, but even leadership in the communities,” the Prilaka member explains. “People are afraid on the one hand and, on the other, many are looking for a way to make a living, even if they do not agree with the system.”

Since 2015, invasions of indigenous territories have increased. More than 70 community members have been killed in the face of the inaction and even complicity of the Sandinista authorities, who have been involved in illegal land trafficking. The settlers’ constant gunfire has caused the forced displacement of more than 4,000 indigenous Miskito and Mayangna people. Communities disintegrate and ancestral lands are left at the mercy of invaders, who destroy the forest with extensive cattle ranching and pollute the rivers with illegal mining.

“Migration, both urban and rural, affects us a lot, because those people who leave have been part of our organizations. They were people with a critical, committed stance, who could lead processes in the communities,” says the Prilaka member. “But they end up leaving the territories and even the country because of the violence”.

The violence, exercised by settlers and the State, has many aspects for the indigenous peoples. Prilaka not only identifies violence as dispossession of territories, but also violence against women to prevent processes of inclusion.

“Violence limits what can be done. For example, before, we could conduct territory surveillance in many areas to assess how far settlers had come and what they were doing. But now, we don’t know exactly how many acres have been invaded, or how many settlers are really inside the territories,” says the Prilaka member. He says with a tone of despair. “We don’t know the critical situation of endangered species, of large mammals like deer and tapirs.”

“Then, if you don’t have accurate data on how the problem is evolving, it’s difficult to grasp… but it’s also difficult to address it properly,” says the indigenous person.

Amaru Ruiz is the director of Fundación del Río, an environmental NGO that was closed and confiscated by the Ortega-Murillo regime. Also in exile in Costa Rica, the organization presided over by Ruiz works hand in hand with indigenous peoples, especially those living in the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve. The environmentalist shares all the difficulties mentioned by Prilaka and, although reserved about discussing the new strategies they have developed to continue activism internally within the country from exile, he assures that the trust built over more than 30 years with the territorial network is the key.

“First, the conditions are not the same as before, and that implies establishing new security and monitoring strategies for what happens in Nicaragua. Thanks to the trust we have built, people continue to be interested in supporting environmental advocacy,” recounts Ruiz. “But we have also learned to better master satellite systems that allow, for example, monitoring fires and forest coverage affected by land invasions and mining.”

The information gathered through technology is combined with what they still manage to collect in the field and the leaked information that is still provided by state workers. Ruiz says he has a daily ritual: checking La Gaceta, the official newspaper of Nicaragua, every day to track the mining concessions that the Ortega-Murillo regime grants not only to Canadian and American transnationals but more recently to the Chinese.

“There is a significant need, especially towards international cooperation and the cooperation agencies of the United Nations that are in the country: demanding that the regime at least make transparent the information about the support they are receiving,” proposes Ruiz. “Or that they publish project execution reports that allow for a more or less official understanding of these projects.”