An exile

will be so for life,

and for death

Mario Benedetti

A loud noise

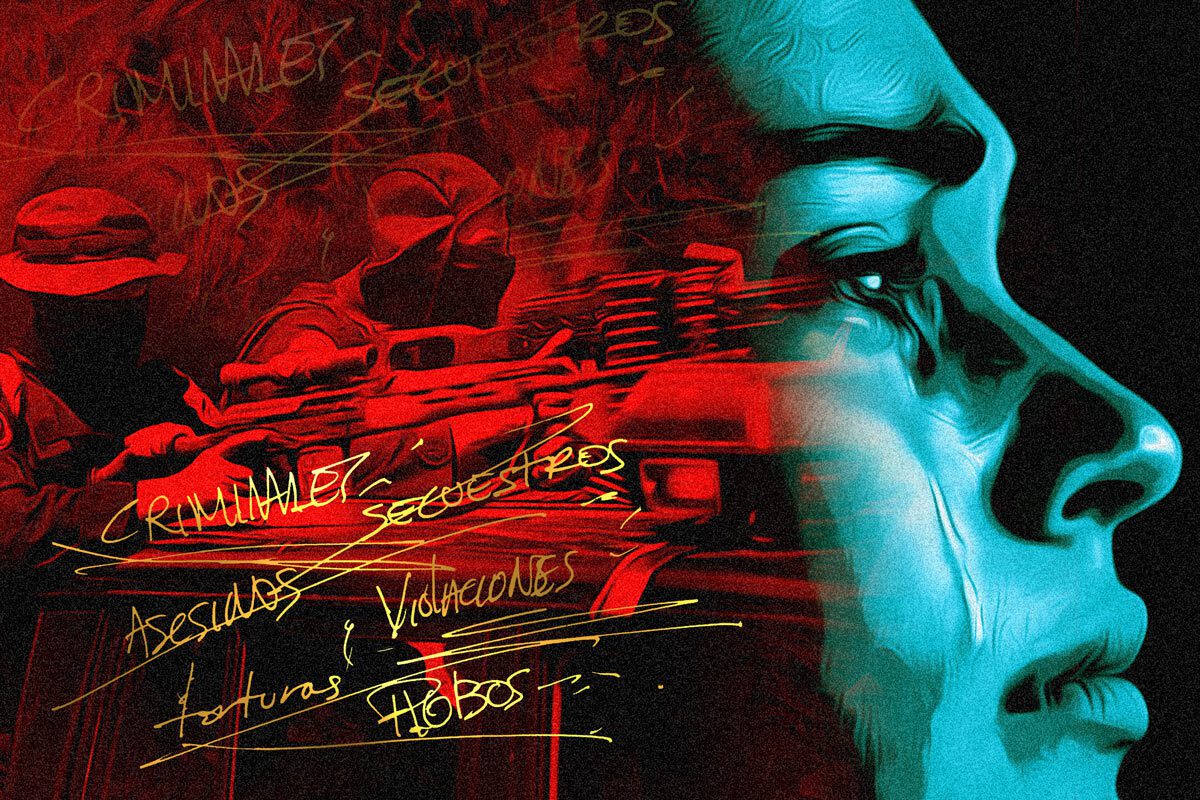

She dropped to the ground instinctively, curling into a fetal position and covering her ears. The thunderous crack of fireworks echoing through the streets of Pamplona, Spain, on a July night in 2018, felt eerily similar to the gunfire of snipers attacking an opposition march in Managua just two months earlier, on May 30. At that moment, Luisa was transported back to the massacre of young protesters, the masked police officers, and the paramilitaries armed with war weapons. But it wasn’t gunfire—it was the fireworks of Sanfermines, one of Spain’s most famous bullfighting festivals.

Surrounded by a sea of people dressed in white with red scarves tied around their necks, Luisa could feel their puzzled and mocking stares as she remained huddled on the pavement. Her heart pounded furiously, and her hands shook uncontrollably.

“Every time the fireworks went off, I felt like I was going to die. My body just wouldn’t stop trembling,” recalls the 28-year-old, who fled Daniel Ortega’s regime in June 2018. That week of festivities became a waking nightmare, pulling her back into the terrifying memories of state repression she endured between April and June of that year in Managua and Carazo.

The fireworks eventually stopped, but Luisa’s mind didn’t. It replayed the mortar rounds fired by young protesters defending themselves against police and paramilitary attacks in the courtyards of Managua’s Metropolitan Cathedral on April 21. She saw again the chaos of the stampede, the screams of dozens fleeing gunfire from repressive forces on May 30 at Avenida Universitaria, after a peaceful march in support of the mothers of those killed during the protests. Her thoughts lingered on the armed convoys of men with AK-47s storming her city to dismantle barricades of resistance and on the relentless 24-hour pursuit that forced her sudden exile to Spain, pushing her through at least three safe houses in Managua before she fled.

“I’m constantly on edge. I always feel like I’m in danger,” she admits. It’s not surprising. Luisa endured the harshest months of state repression during the 2018 civic uprising.

According to the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL), between April 18 and June 30 of that year, 257 people were killed by government forces. June alone saw the deaths of 134 opposition members during Operación Limpieza (Operation Cleanup), one of the regime’s bloodiest campaigns to crush citizen resistance across Nicaragua.

—And how does everything you experienced still affect you?

—I have problems with crowds and loud noises. I always think that if something happens, I won’t have time to escape. I can’t go into a nightclub because I can’t see people’s faces, and I think someone will come to kill me.

The fireworks episode was just the beginning of a torturous process triggered by her exile in Spain. To help her calm down, her father sent her to live for a few months in a remote Spanish village in August 2018. She found some peace there, spending most of her days sleeping in a room where sunlight never entered. Not because it lacked windows, but because Luisa chose to keep them shut. From her window, she could see a distant mountain range covered in pine trees and clear skies, a landscape she ventured to explore only once.

By September, she returned to Pamplona, where her panic and anxiety attacks became more frequent, often ending in the hospital.

Her mind became a constant battlefield, tormenting her with thoughts that she was a bad person, a coward, and insensitive for fleeing Nicaragua instead of staying to fight for freedom. She agonized over going into exile while countless young people continued resisting the dictatorship. This mental anguish is known in psychology as survivor’s guilt—a relentless sense of responsibility for the suffering or deaths of others. “I questioned myself every single day because I felt I should be fighting in Nicaragua. I didn’t understand what I was feeling until I started therapy,” she shares.

It was four years ago that Luisa began therapy. Her post-traumatic stress disorder, which had led to persistent depression, also triggered delusions of persecution.

“I struggle with depression and anxiety. I take escitalopram, lorazepam, and quetiapine. Without them, I have panic attacks that make my heart race uncontrollably. At first, I thought caffeine was causing my anxiety, but it’s actually the aftereffects—stemming from the persecution I went through. Exile doesn’t affect everyone the same way,” Luisa acknowledges.

She admits to being afraid of Spanish police officers because, in Nicaragua, it was the police who hunted her down. Nights are still restless—she wakes up abruptly, haunted by the faces of people she saw die.

—How are you now?

—I’m going to boxing classes.

—Is that therapeutic for you?

—It gives me the false sense that self-defense will help improve my mental health. I’ve been boxing for a couple of years now.

This Luisa is very different from the one who lived in Nicaragua. Back there, she frequented the lively bars of Zona Rosa in Managua. Back there, she dreamed of finishing her psychology degree and pursuing a master’s in criminology abroad. Exile shattered her life plans.

—Are you feeling better?

—Yes, I’d say I am. I feel like I can do more than I thought I could without constantly worrying about my anxiety. I didn’t want to work as a caregiver for the elderly, so I’m now studying a vocational program in Clinical Laboratory Science.

***

The life that was

Exile is synonymous with loss, suffering, fractures, orphanhood, and loneliness. Back home, they had friends, a home, a job, a support network, a family… back there, back there, back there.

The exile stories of the 20 Nicaraguans interviewed for this report are deeply marked by the repression they endured in 2018. Although not all of them were politically active in the same way, they share the same psychological scars: depression, anxiety, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In Spain, the registered Nicaraguan population grew from 26,209 in 2018 to 60,681 in 2022, according to the National Institute of Statistics. The actual number is believed to be even higher, as Spain became the third most popular destination for Nicaraguan migrants, after Costa Rica and the United States.

Pedro, a 33-year-old psychologist from Granada, attended a couple of peaceful opposition marches in Managua, but the fear of being struck by a bullet eventually paralyzed him.

Javier González, a 38-year-old economist from Managua, resigned from his position at the National Port Authority (EPN) when the government ordered the repression of elderly protesters opposing a Social Security reform, which had ignited the sociopolitical crisis.

Pedro decided to leave Nicaragua in September 2018 after, in July of that year, Sandinista paramilitaries stopped his car near the Ticuantepe roundabout, close to Managua. They forced him to open his trunk, unlock his phone, and hand over his wallet.

A friend of his, who had actively participated in the opposition protests, was brutally beaten in the abdomen by regime supporters in his hometown. They also dropped a rock on his head, causing severe brain injuries. “I’m not staying here. I’m leaving,” Pedro thought at that moment. He now lives in Barcelona, Catalonia.

Javier fled Nicaragua on June 9 after EPN regime operatives threatened him for participating in anti-government protests. Before seeking refuge in Spain, he hid in Guatemala and Belize from June to December. “They told me they were going to settle the score, that they’d finish me off,” he recalls.

Javier’s father was a prominent figure in the Sandinista Popular Army (EPS) in the 1980s and was once close to the former Minister of Finance, Iván Acosta, who has been sanctioned by the United States and is reportedly being fired by the dictatorship.

Now living on the Mediterranean coast in Alicante, Valencia, Javier knows that betrayal of the Sandinista Front, the ruling party, is punishable by imprisonment or death.

“Repression in Nicaragua, which deepened after 2018, has been one of the most lethal in the region due to its sustained nature. In Nicaragua, there isn’t a single social sector that hasn’t been repressed, and exile itself is a violation of human rights,” observes Camila Omar, a lawyer with CEJIL.

In the last century, several studies examined the mental health effects of political repression on exiled Argentinians and Chileans. However, in Nicaragua’s case—marked by decades of war and violence that triggered a major wave of exile in the 1980s—there are no comprehensive studies addressing the trauma these processes inflict.

“Mental health issues are the most dramatic consequence of political repression,” said Chilean psychologist and researcher Elizabeth Lira in 2022. Lira, who served on Chile’s National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, highlighted exile’s devastating psychological impact.

“Exile is nothing less than a rupture between a person and their place of origin, where they were born and internalized patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion. Leaving—whether voluntarily or under threat to their safety, freedom, or life—is a complex process,” wrote Brazilian psychiatrist Sandra Lorena Flórez Guzmán in her research Impacts of Exile on Mental Health.

“Exile meant a harsh punishment capable of damaging mental health,” concluded Argentine sociologist Soledad Lastra in her publication The Political Trauma of Exile and Return in Chile During the 1970s and 1980s.

Psychologist Mariangeles Plaza, coordinator of the psychological support service at the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid (CEAR), has firsthand experience of the trauma endured by Nicaraguans who arrived in Spain in 2018.

At CEAR, young people who actively participated in student protests sought help. “The consequences of repression are very clear—it impacts our psyche,” says Plaza, an expert in trauma caused by political violence. Many patients reported nightmares, fear, anxiety, and flashbacks of the repression they experienced.

“When someone doesn’t have the tools to navigate this process, they fall into addiction or anxiety. Psychosocial trauma is a kind of war trauma,” Plaza explains.

In Costa Rica, Ruth Quirós, a clinical psychologist specializing in trauma from the Nicaragua Nunca Más Human Rights Collective, observed similar patterns among Nicaraguans in exile. “The main diagnoses are post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. Symptoms often include avoidance syndrome, hypervigilance, reactivity, self-destructive or self-sabotaging behaviors. It’s hard to reconnect with the life we once knew,” she notes.

Pedro and Javier felt their identities erode upon arriving in Spain. Both experienced fragility and frustration. For Pedro, life changed when he managed to regularize his immigration status—not because the Spanish government granted him refugee status, but because he formed a civil partnership with a man he met in Spain. For Javier, however, uncertainty deepened when the Ministry of the Interior denied his asylum application.

“I periodically relive an unhealed pain; these are wounds that tear you apart. I had an overwhelming sense of loss. Another thing that weighs heavily is feeling like you’re worthless. We’re subjected to working conditions that don’t match our abilities. I’m an economist and graphic designer, but I can’t access the Spanish job market,” says Javier.

His emotional crises worsen when he dreams of returning to Nicaragua. In his nightmares, he finds himself discovered and fleeing down wide streets that gradually narrow, only to be blocked by walls that trap him.

“I relive that panic, and when I have those nightmares, I wake up the next day feeling emotionally drained, sad,” he shares. It is in those moments that the pain of existence resurfaces, accompanied by memories of the life he once had in Managua—a life where he was happy and felt fulfilled.

—Have you started seeing a psychologist?

—I’ll start soon. Should I seek help? Absolutely!

***

The breaking point

Juan‘s downward spiral had reached a breaking point. His forearms bore the purple marks of attempts to inject mephedrone—a recreational drug in Spain often linked to extended sexual encounters among men, raising public health concerns.

The first time he tried to use drugs intravenously was in June 2022. Alone in a dimly lit room, he felt nervous and afraid, unaware of the hellish door he was about to open.

Just weeks before, Spain’s Ministry of the Interior had denied his asylum application. The resilience he arrived with began to fade under mounting challenges: a job where he felt unfulfilled, unresolved childhood traumas resurfacing in adulthood, and an overwhelming sense of loneliness and disconnection.

“It was a combination of things that led to my collapse,” Juan admits. He left Nicaragua on December 5, 2018, and before settling in Zaragoza, in northeastern Spain, he lived in a tiny village with about 100 elderly residents.

“My addiction stems from feeling like I don’t belong and the isolation of being in exile,” he confides during a September afternoon in Madrid. That month, he traveled to the capital to escape people in his current city who tempted him to relapse.

In Nicaragua, Juan worked as a banking analyst until the sociopolitical crisis led to staff cuts at his company. Before migrating, he was detained for over six hours in Managua by police officers who falsely accused him of theft.

“I turned to drugs to escape my problems. I didn’t even realize when I became depressed. It hit me that I had a drug problem after I resolved my immigration status, only to be left with the addiction,” he reflects.

Psychologists from CEAR and the Nicaragua Nunca Más Human Rights Collective interviewed for this report agree that exiled individuals often exhibit self-destructive or self-sabotaging behaviors, ranging from eating disorders to drug and alcohol use.

Five of the twenty testimonies collected by DIVERGENTES in Spain involved addictions to drugs and alcohol. These individuals, driven by vulnerability and despair, seek relief from their heavy burdens in substances or medication.

Exiled Nicaraguans in Spain often find themselves in precarious jobs that undermine their self-esteem. The situation worsens for those without legal authorization to work, as their professional skills—built in Nicaragua—are undervalued by both the state and employers. Experts highlight that access to the job market is a critical factor in shaping exiles’ social identity.

Juan always knew he would have to take whatever job he could find upon arriving in Spain. “I worked in a nursing home caring for the elderly, in a hardware warehouse—I had to adapt,” he recalls. But as his sense of not belonging deepened, he sank further into his addiction, which developed between July and August 2022.

By December of that year, he felt trapped in a repugnant practice, incomprehensible to others but deeply painful to him. Yet, he summoned the courage to seek help. He wanted to leave behind the days of being consumed by drugs in dark rooms while life slipped away. He had hit rock bottom—his breaking point.

—How are you now?

—Better, much better in terms of work. I’m no longer stuck in jobs that don’t suit me. Socially, I have a circle of friends and an active social life.

Pablo now resembles the person he was before June 2022, when his addiction to mephedrone began. Therapy, anti-anxiety medication, and antidepressants have helped him recover and rebuild himself. He appears more fit than he did months ago and smiles like someone who has rediscovered the meaning of life. Before ending the interview, he insists that his story shouldn’t be remembered as just another tragic tale of addiction. Instead, he hopes people draw positive lessons from his experience.

—Like what?

—I don’t have wounds from exile—I have experiences of exile. Yes, there are challenges and obstacles, but if you make the right decisions, things get easier. Along this journey, I’ve untied emotional knots and started to feel like I belong to this society.

Pedro says he’s happy. He has resumed writing poetry, which he plans to compile into a blog.

***

The power of reinvention

From the heights of the Collserola mountain range, Barcelona sprawls beneath you. In the distance, the towering spires of Antonio Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia rise against the horizon, while the Mediterranean stretches all the way to the northern coast of Africa. The city’s near-perfect grid unfolds, a symbol of its cosmopolitan nature.

It was here, at this scenic overlook, that Pedro came to terms with his reality and his new life as an exile. “I spoke to myself gently: ‘This process doesn’t define you; you have the power to transform it,’” he repeated like a mantra every day during the three months he lived with a host family in the Sarrià neighborhood.

The house where Pedro stayed in late 2018 was located in an upscale area of Barcelona, near the wooded trails of Collserola Natural Park. At that time, his emotions felt like clothes endlessly tumbling in a washing machine.

“I faced the challenge of rebuilding myself personally and socially. I had no companionship; I was alone. I found a job as a kitchen assistant, a poorly paid and grueling role that made me question my self-worth,” he recalls. It wasn’t starting from zero—it was starting from less than zero. He felt sadness, frustration, and helplessness.

However, Pedro embraced this new chapter as a difficult challenge, akin to the effort it took to run along the steep mountain trails. In sports, he found a refuge to process and release his exile. Every day at 4:00 p.m., he would run for 45 minutes until he reached a viewpoint where, for a moment, any problem or pain became insignificant.

“There, I could put everything into perspective. What I had in front of me was bigger than my problems, so I’d breathe until they felt smaller. And when the burden felt lighter, I’d decide to go back down,” he recalls. He maintained this ritual during his time in Sarrià.

Mariangeles Plaza, a psychologist with CEAR, notes that exile can have a positive side by fostering resilience. “People find their strength, they become stronger—that can be a silver lining amidst the harm of exile. I’ve seen it often in Latin American countries,” she explains.

Having worked in Mexico and Colombia with victims of torture, Plaza has learned that, after long healing processes, a moment of redefinition and new meaning eventually emerges.

In six years of exile, Pedro has lived in 12 homes across various neighborhoods in Barcelona. He’s worked as a waiter, babysitter, and salesperson, enduring more frustrating days than fulfilling ones. Yet, he views those moments of frustration as opportunities to recognize his ability to reinvent himself and to choose what to hold onto or let go.

“Things gradually stabilize, which translates into social stability. With that stability, you start envisioning future possibilities. Before, I dreamed of gaining legal residency; now I dream of a different kind of stability—starting a family, settling down. Exile has given me confidence and security,” he confesses.

In the mornings, Pedro works as a salesperson in a sports store in Barcelona’s old town. In the afternoons, he studies Social Integration to reconnect with the identity he had in Nicaragua.

During his rare free moments, Pedro runs along the wooded trails of Collserola or swims in the tranquil waters of Mar Bella beach. “In my efforts to overcome and care for myself, nature has always been my best ally,” he says.

Like Pedro, other Nicaraguans have resumed projects that bring meaning to their lives. Sandra has begun studying fashion and clothing design in Madrid, with plans to open her atelier in the near future. Edwin, Carlos, Francisco, José, Juan, Rosa, Elena, and Wendy are also piecing back together what they once were. If there is one silver lining to the painful process of exile that began in 2018, it is the ability to forge a new identity, piece by piece, in another country.

In summary,

we are not who we are

nor who we once were.

Mario Benedetti

This article includes 20 testimonies from exiles across 12 Spanish cities. Only two individuals chose to use their real names; the rest requested anonymity for fear of reprisals against their families still in Nicaragua. This report was produced as part of the “Workshop and Master Classes” project by DIVERGENTES, with support from the German Federal Foreign Office and the German Embassy in Costa Rica.