It was Marco‘s first day of class. After an unusual introduction from the new professor, the four students in the classroom looked at each other, clearly confused and reluctant. The professor had just openly admitted that he didn’t have a syllabus or a lesson plan for the semester. In fact, he said he was only given two months to prepare, that the university didn’t provide any materials, and that the department just told him, “These are the groups and classes you’ll be teaching.”

The professor’s speech was long and seemed more like an attempt to justify that, due to the lack of a structured syllabus, he would be improvising assignments and subjects during the first week. In reality, that was the reason he strayed from his introduction, which turned into a kind of venting session that he probably didn’t realize he needed.

In his four years of university, Marco had never seen anything like it. The classroom was emptier than ever. In the first few minutes of class, he expected more students to show up late, but no one else came. That day, it was just him and three other people.

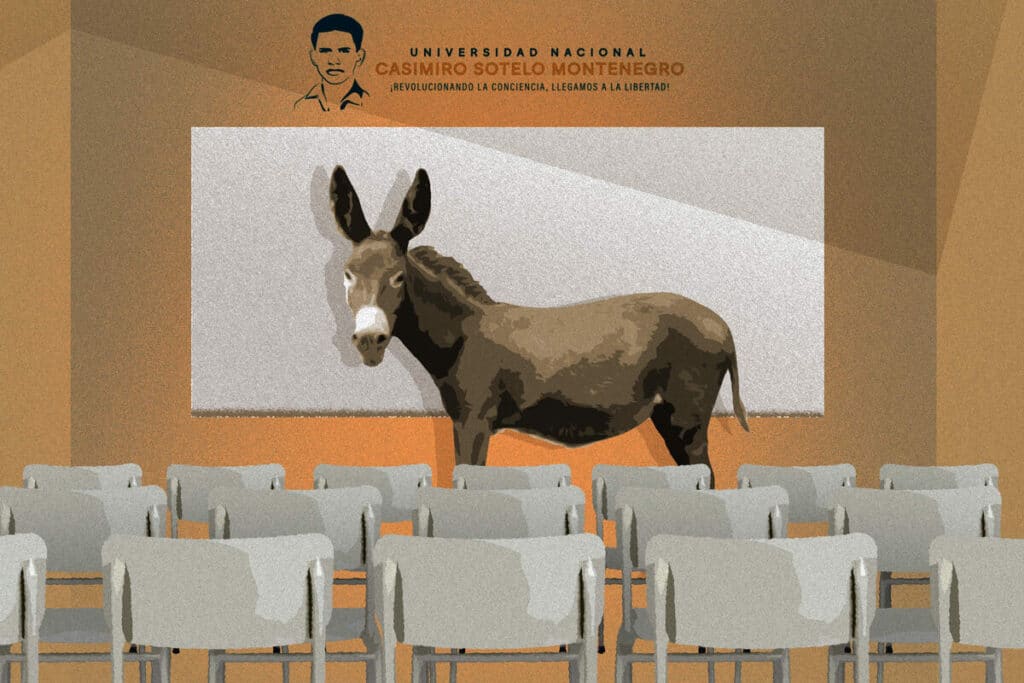

Marco knew that his class group was much larger, but he didn’t know how many had decided to finish their degree at this university. He only had two courses left to finish his degree, which is why he chose to stay at the Casimiro Sotelo Montenegro National University (UNCSM), the name that replaced the confiscated Central American University (UCA). Although he had anticipated that his classes wouldn’t be the same as under the Jesuit administration, nothing had prepared him for such a level of irresponsibility.

Children’s classes

After a few more words, the new professor decided that the class would be conducted through dictation for the rest of the course, and instructed the students to take out their notebooks and write down what he was going to read. For Marcos, this order brought back really old memories from high school. “As if we were little kids,” he said.

And so, that first day of class went by amidst dictations and puzzled glances. The professor read information he had just found online, and the students wrote it down like photocopiers. What they didn’t know was that this would not be limited to that day but would repeat throughout the entire course. The lesson plan the professor had promised never materialized, and Marcos and his few classmates spent the following months attending improvised lessons.

In the classroom next door, a similar situation was unfolding with another professor who had no teaching materials to use. In fact, the same scenario played out across the entire UNCSM campus. Despite the five months the de facto authorities had to prepare academic plans—or to reuse the ones that former UCA professors had—none of the new instructors had an adequate syllabus.

The few prepared professors vs. the majority of improvised ones

In these eight months UNCSM has operated, the decline in the quality of education has been evident from the beginning. Each student’s academic experience has varied depending on the professor, revealing the clear disorganization within the institution’s departments. The result for the students has been clear: “We’re not learning anything,” they say.

While professors like Marcos’s merely dictate notes without any other form of instruction, others simply play YouTube videos to explain topics or only attend classes when their absence becomes too obvious. “The administration tells us not to miss classes, but they ask us to be understanding of the professors who don’t show up,” says Claudia, another student, whose name we’ll use to protect her identity.

The roulette between the few professors who adequately prepare for their lessons and those who show up to improvise wasn’t just present during the first academic cycle but continues to this day.

During the first semester at UNCSM, the different program coordinators excused the new changes brought about by the confiscation, including the removal of the entire UCA teaching staff and the loss of syllabi for each course.

They also made excuses for the unexpected schedule changes and class cancellations. “This is due to the changes, folks. Please, let’s be understanding,” they would tell the students.

The promise of a normality that never comes

The coordinators assured everyone that the university would soon stabilize and return to normal, as if the confiscation had never happened, but normality never fully returned.

“There are days when the professor just comes to class, spends time on their phone, and tells us to do whatever we want. Or they make us watch videos but don’t explain anything afterward, don’t teach us anything. That’s how every day goes. You never know what to expect,” says Luis, a senior student.

Only a handful of professors come to class to teach their subjects with structured lesson plans, aligned with the course objectives, topics, and clear evaluation methods. Most of these few professors were already teaching or still teach at the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNAN).

Aside from these teachers, the overall faculty at UNCSM lacks proper course programs to teach higher education, adequate prior preparation, and even supervision from the university’s coordination. “It seems like even they don’t know what they’re going to teach week to week. It’s been poorly organized,” says Marcos.

Students forced to learn on their own

Elisa attended her class on time. Her professors had been debating for weeks how they were going to evaluate the students. Although quite some time had passed since the start of classes, the professors still hadn’t decided how they would assign grades. “It was clear they had no structure or preparation,” Elisa comments.

Since UNCSM resumed operations, Elisa had hoped to continue progressing in her education, but now, instead of moving forward, she feels stuck. Although the new faculty asked students what knowledge they had about their subjects to pick up where they left off, throughout the course, these professors ended up covering topics the students had learned long ago, and even assigned projects they had already completed.

Faced with the lack of new knowledge, many students have had to study independently outside the university. “These changes don’t motivate us, forcing us to find alternative ways to learn. Essentially, the UCA students are the ones teaching the new professors how to develop the classes, assignments, assessments, and other things,” says Elisa.

“There’s a significant decline in every sense. None of the staff are making an effort to provide the quality education they talk about,” she adds.

High school methods

That day, Elisa brought a poster with the information she was going to present. In the confiscated university, PowerPoint presentations or other digital tools via projectors were no longer used. The new staff didn’t know how to use the projectors available in the classrooms. As a result, students were forced to go back to using posters and cardboard displays, reminiscent of their high school days.

The topic Elisa was going to present was something she had already covered with her previous professors. In fact, that week, Elisa and her group had been assigned several tasks they had already completed before the university was confiscated. So it was easier for her to recycle her old assignments and simply change the university’s name on the presentation.

In reality, during the months she had been studying at UNCSM, she felt she hadn’t learned much. There was no demand, no research, no practical exercises, nothing new. “I’ve resigned myself to the fact that I’ll just get my degree, but I’m not going to learn anything new,” she says.

This sentiment is shared by many. Luis says that he feels discouraged about finishing his degree. Nothing is the same as it used to be. “I’m very disappointed because the way the professors teach important classes feels too simple. It’s just dictation, and that’s it. There’s nothing dynamic, no exercises to practice what we’re learning,” he explains.

If a student dares to complain to a professor that they don’t like the class or that they’re not learning anything, the professors respond aggressively. “The teachers humiliate students with inappropriate language, not how a teacher should speak to a student. They always contradict our opinions. They tell us we think we know it all,” he says.

Propaganda at Casimiro Sotelo

Luis’s group isn’t the only one experiencing this. Just like the quality of the lessons, the treatment from professors is also unpredictable. Silence and secrecy reign in the classrooms, intimidating the students.

Although many professors don’t mention the country’s socio political situation, there are some who are openly loyal followers of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo’s dictatorship and who inject political propaganda from the regime into their lectures.

While these professors speak freely about their political preferences, students cannot do the same. They can’t even complain publicly without risking having their enrollment denied for the next semester.

“There are many students who have been denied enrollment, even though they weren’t involved in politics. Many of them had complained about the chaos and disorganization at the university, and argued with professors because they weren’t teaching well. We know they were denied enrollment because of that, even if they weren’t told that. So it’s better to stay quiet,” Luis mentions. Academic freedom is something else that was confiscated by the regime.

Quality of education, an unfulfilled right

The quality of education in universities is a right mentioned in different state laws and is supposed to be guaranteed by the National Council for Evaluation and Accreditation (CNEA) through the Higher Education Quality Assurance Model.

The General Education Law, Law 582, states that the quality of education “encompasses the conception and design of study programs that are an important part of the curriculum, as well as the performance or achievements of the students.”

Meanwhile, the Law Creating the National System for the Assurance of Education Quality and Regulating the CNEA, Law 704, asserts that the system’s principles should be those of progressiveness, legality, credibility, and national and international recognition—principles now questioned in the newly confiscated universities.

From December 2021 to September 2023, Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo’s dictatorship revoked the legal status of 30 higher education institutions. Most of these institutions have resumed operations under the leadership of individuals loyal to the regime.

The CNEA has held meetings with the presidents of these confiscated universities to grant them accreditation and has supported the takeover of these educational institutions, along with the National Council of Universities (CNU). In a social media post on July 26, 2024, the CNEA announced that it is currently providing support to UNCSM “in pursuit of institutional accreditation.”

The regime’s improvised universities

The regime has claimed that these universities produce great professionals and maintain educational quality, “but in reality, they are just large improvised universities where nothing useful for professional life is taught,” says Adrián Meza, former president of the confiscated Paulo Freire University.

“In these universities, they teach bland science and technology—meaning it lacks critical thinking. It’s the complete opposite of what science and technology should be. Now, they are the great improvised universities, created and shaped in the image of the Ortega regime. This creates a terrible void in knowledge, culture, and professional training,” the scholar explains.

To ensure quality education, a university must offer good teachers, academic freedom, and an environment where debate on study topics can flourish, says Mario, a former UCA professor consulted by DIVERGENTES, who requested anonymity.

“The word ‘university’ comes from ‘universe.’ You need spaces where students can ask questions, experiment, and learn. That’s the basic requirement, though there are many more,” he elaborates.

Without academic freedom and teacher preparation, there is no university

If students lack academic freedom and instead face censorship, the university becomes more of a catechism center, Mario asserts. For universities to fulfill their educational purpose, there should be no forbidden topics, taboos, or dogmas—quite the opposite.

“Real universities are born of reason, logic, debate, experimentation, and the production of knowledge,” he states.

However, the preparation of competent teachers who fulfill their role as educators is also crucial for the development of quality education. Without good teachers, there can be no quality teaching. “One cannot exist without the other,” he notes.

Before its confiscation, UCA required a high level of preparation from its professors to meet the standards set by the Association of Universities Entrusted to the Jesuit Order in Latin America (Ausjal).

“UCA was part of the Ausjal network and the global network of Jesuit universities. Faculty from all UCA departments would visit these other universities to share, study, and conduct research,” Mario explains.

In line with Law 704 and Ausjal’s requirements, professors were responsible for designing programs using a variety of methodologies. To do this, they needed to research the best approach for their group of students.

These academic programs evolved with the students, Mario points out, to avoid the routine repetition of something that hadn’t worked in the past. Long before implementing the programs, the professors would carry out exploratory activities to understand the expectations of the group they were teaching and their knowledge levels on the subjects. These and other demands required by Law 704 and the CNEA are not being met at UNCSM.

“Several times, the semester had already started, but for the first few classes, there was only someone there to watch over the classroom because they still hadn’t found a professor. They told us we had to wait a few weeks until they could find someone, and during that time, we didn’t have any classes,” recalls Marco.

Students have no other choice

Marco returns to the campus that was once a true place of learning to collect his diploma. He has completed the two remaining courses, in which he admits he didn’t learn much. At least, he is grateful that most of his education came from UCA and not Casimiro Sotelo.

Marco’s diploma is part of the first batch of degrees awarded by UNCSM, and although it doesn’t bear the name of the university where he spent nearly his entire academic career, he’s thankful to have finished that chapter of his life.

He takes his diploma and heads home with a heavy heart. He says he feels great sadness for the new students who will never know the experience that UCA offered and for those who still have time left because they once knew it but will never have it again.

As he leaves, the red-and-black flag is visible in every corner of the university. The new staff wear slogans from a revolution that took place nearly half a century ago. The walls are covered with the new name, Casimiro, attempting to replace the former Jesuit identity.