There, where the humid heat feels like it could boil time itself and the roar of the waves merges with the whistle of the wind through the forests, lies Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast.

This sprawling paradise is traversed by the winding Wangki River, which snakes through plains, jungles, and hills before its reddish waters mix with the white foam of the Caribbean Sea.

For generations, the indigenous peoples—guardians of these ancestral lands—have lived at the unique crossroads of gratitude for nature’s gifts and profound respect, tinged with fear, for the fierce ocean winds that have shaped their lives.

The elders remember stories passed down from their ancestors about Prahaku, the Miskito god of the clouds, space, and swirling winds. They could sense Prahaku’s presence simply by observing the sky and feeling the air. “Pasa ai prauka plikisa,” they would say: “The wind is getting angry.” And they knew what to do.

They would exhale in relief when the last day of Yahbra kati—the Month of Winds, or November—came to an end.

“Our ancestors learned to live with the winds and the sea. They knew the sea could bring both life and death, with its winds and its great waves,” says Nelson, a Miskito man in his seventies. He hasn’t seen the Wangki River in over two years.

“Our community knew what to do and where to go; they didn’t fear the dark skies when the rains ended…” he reminisces in the measured, deliberate way elders often speak.

A new fear from the roads

Now, the younger generations don’t know how to face this new fear that has invaded their communities—carried by the sound of boots, engines, and gunfire.

In the villages, people speak fearfully of groups of armed men wielding chainsaws, maps, and trucks that roar as they carve out roads where once there were only trails.

Nelson fled from them. In 2021, he crossed the Coco River into Honduras with part of his family and hasn’t returned, fearing he might meet the same fate as two relatives killed in Kiwas Tara, further down the Coco River, where he spent most of his life.

“It was the Spaniards and the Army,” accuses Nelson, a Miskito exile in Honduras whose real name a non-governmental organization has requested be protected to avoid risks or reprisals should he ever return to his community.

His story is a common nightmare in these lands: the “Spaniards”—a term locals use for mestizos—arrived in small armed groups, settling on the outskirts of communities where Nelson and his family had lived for generations.

First, they felled the largest trees and sold the lumber. Then more men arrived, with more weapons and chainsaws, pushing deeper into the community. “We tried to drive them away, and they fired on us,” he recalls.

Then came the worst: they burned their crops and homes, poisoned their hunting dogs, and one terrible day killed two young men from the community who had followed the tracks of a wild pig too far from their homes.

Cataclysms and tragedies

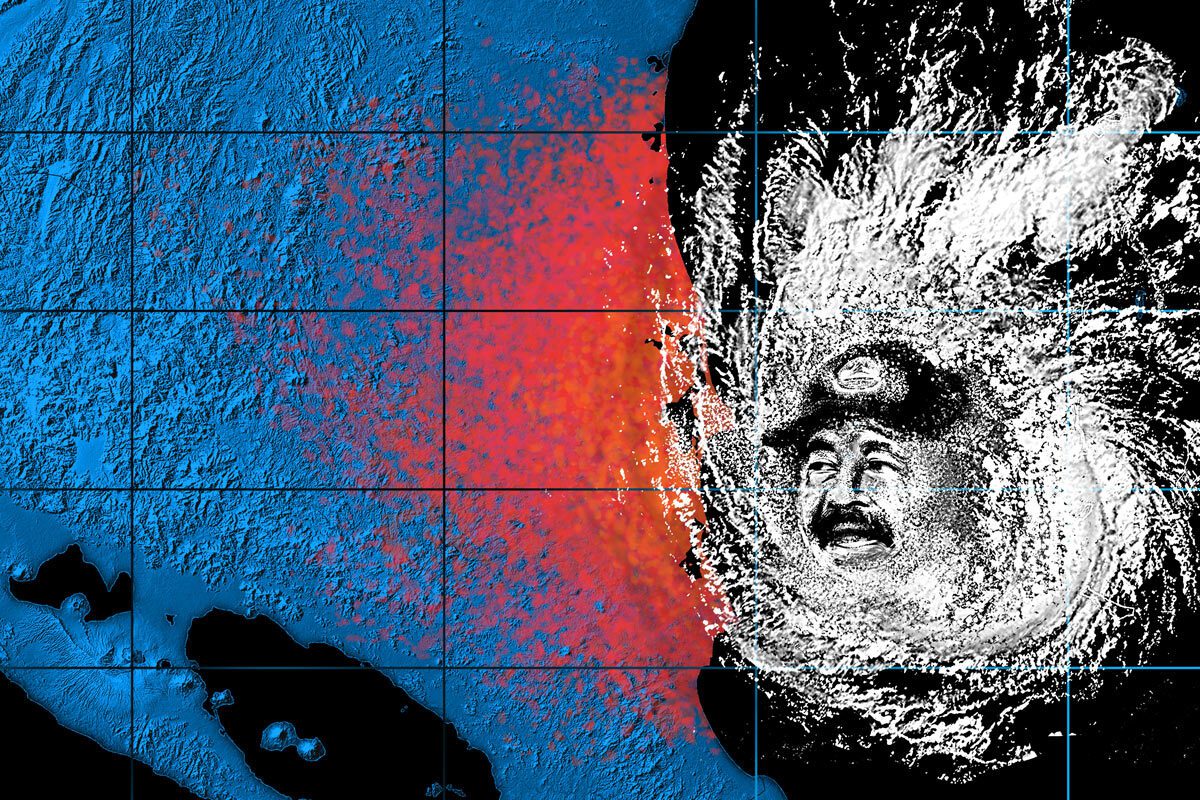

In Nicaragua’s vast and verdant North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCN), indigenous communities have endured countless hurricanes over the centuries.

Between 2007 and 2024—the period of Daniel Ortega’s prolonged grip on power—the region has been battered by four hurricanes and numerous tropical storms. Stretching further back to 1979, the Caribbean Coast has weathered 10 hurricanes of varying intensity and devastation.

These relentless natural disasters are a direct result of the region’s position along the Atlantic’s notorious “hurricane corridor.”

Yet, as Ross, an indigenous rights defender operating in secrecy within Nicaragua, explains, an even more devastating force has torn through these lands: the repressive policies of Daniel Ortega’s regime.

This political phenomenon has devastated not only their lands and livelihoods but also something far deeper and harder to rebuild—the social and cultural fabric that has held these communities together for centuries.

“In indigenous cultures, respect for all natural phenomena, including hurricanes, has always been taught,” Ross explains. “But nothing prepared them for the destruction of their ways of life.”

Ross, a human rights activist and former employee of a civil organization dismantled by the Nicaraguan dictatorship in 2022, has been living away from her community for nearly three years due to threats from the Sandinista police.

“Ortega, in 17 years of dictatorship, has achieved what centuries of hurricanes could not: dismantling communities and forcing them into a coexistence with mestizo invaders that guarantees the government’s extractive plans and social control over these ethnic groups,” Ross denounces.

No one escapes the political misfortune

For Ross, neither the Miskito, Mayangna, Rama, nor Garífuna peoples, nor Afro-descendants, have escaped the destructive policies of the regime.

“If they’re not taking their land or invading their territories, they’re stripping them of their rights. Imagine the kind of colonization we’re living under—on Rama Cay, where about 200 Rama people live, they imposed a police station and a naval post,” she says.

“Look at what happened in Bluefields—they shut down the Moravian Church, the main religious representation of Afro-descendants in the southern Caribbean,” she points out.

She adds that in communities like El Rama, Nueva Guinea, El Ayote, Paiwas, Muelle de los Bueyes, and El Tortuguero, at least 12 small Catholic and evangelical churches have been left without priests or pastors.

“They fled because of the repression. The police don’t care whether you’re Catholic, Evangelical, Moravian, Miskito, or Afro-descendant—they come to silence you or drive you out,” Ross denounces.

Institutional devastation: 66 NGOs eliminated

One of the key pillars of indigenous resistance in recent years has been the work of local Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) dedicated to protecting territorial rights, culture, and community life.

Since the start of Nicaragua’s social protests in 2018, Ortega’s regime has shut down over 5,500 civil society organizations across the country, 66 of which operated in Nicaragua’s Caribbean region.

According to Tininiska Rivera, an indigenous rights defender and daughter of the disappeared indigenous leader Brooklin Rivera, “the destruction of these organizations is a deliberate act of cultural genocide.”

Rivera explains that this mass closure has hindered the monitoring of state repression and the invasion of indigenous lands by settlers.

“Organizations dedicated to defending human rights, protecting the environment, and promoting social development were systematically dismantled under fabricated legal justifications, such as alleged non-compliance with fiscal regulations. The true aim is to suppress any reporting of these crimes,” asserts Rivera.

Ross shares this perspective: “Their goal is to erase our identity and silence our voices. NGOs and churches were the only avenues we had to protect indigenous families from abuse.”

The closures have directly impacted vulnerable groups, including impoverished families, women relying on health programs, indigenous farmers, and environmental stewards.

Ross recalls a project she managed in which at least 22 teenage girls, survivors of sexual violence, received psychosocial support to help them heal from the emotional and physical scars of their abuse.

“Where are those girls now?” she asks. “Perhaps they’re reliving the trauma of their assaults or caught once again in cycles of violence.”

Over 600 violations and crimes in 2024 go unpunished

2024 has been especially brutal for the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean Coast.

According to reports presented by human rights organizations to Nicaragua’s independent press, during the first six months of the year, 643 human rights violations were documented against indigenous communities in the RACCN.

These violations impacted 682 individuals. Among the most severe cases were four murders, 74 forced displacements, 49 land seizures, 10 sexual assaults, and 39 incidents of physical and psychological violence against indigenous women.

Other reported incidents include threats, persecution of indigenous individuals by settlers, police, or military forces labeled as “opponents,” destruction or theft of crops and livestock, contamination of farmlands, and acts of intimidation and stigmatization.

Keyla Chow, an activist and representative of the Nicaraguan Caribbean Bloc in exile, highlighted during a conference in San José, Costa Rica, that none of the 643 violations documented in 2024 had been brought to trial.

“Impunity is absolute,” she declared on August 9, during the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples.

“Nothing is happening here,” says the Regime

In the Nicaraguan regime’s official narrative, the Caribbean Coast is portrayed as a haven of peace and security.

In its National Report submitted to the Human Rights Council for the fourth Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in November 2024, the Sandinista regime emphasized “progress” in land titling on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast.

The report claims that since 2007, 23 indigenous territories and two complementary areas have been titled, covering a total of 38,426 square kilometers.

“These titles have benefited 315 indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, granting them full communal ownership of the lands and natural resources within their territories, as officially recorded in the Public Property Registry,” the regime proudly claims.

A state complicit in violence

Despite these claims, Anexa Alfred Cunningham, an indigenous rights expert with the UN Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples, asserts that while the state has made progress in demarcating indigenous territories, it has failed to guarantee the right of communities to live peacefully within them.

“The Ortega government has allowed—and even encouraged—the invasion of indigenous lands by armed settlers, most of whom are linked to activities like extensive cattle ranching and mining,” Cunningham states.

This process has triggered mass displacement and unprecedented environmental destruction in Nicaragua’s Caribbean region.

According to indigenous organizations, since 2015, over a million hectares of indigenous lands have been invaded, deforested, and converted into cattle ranches. More than 4,000 indigenous people have been displaced from their ancestral communities, and at least 2,000 have sought refuge in Honduras and Costa Rica.

The life that was lost: A war against indigenous peoples

Nelson has witnessed both paradise and hell in his 70 years living in the ancestral territories along the majestic Wangki River.

What was life like before the settlers, and what has been lost after years of conflict?

“Luxury and development, as they think of it in the Pacific, never existed here. Luxury was having a battery-powered radio and getting your hands on white sugar,” he recalls.

Yet Don Nelson recalls a life that, while marked by poverty, was simple and free. Families roamed the land, living in deep connection with nature.

For them, nature was not merely a backdrop but their home. The rivers and springs quenched their thirst and nourished their crops; the forests provided firewood, game, and medicinal plants.

They lived off what they hunted and fished, cultivating grains and vegetables under the open sky, and resting peacefully at night in the jungle’s enveloping darkness.

“Oh, how beautiful it was to roam for miles on a hunt, never fearing you’d run into a Spaniard with an AK,” he reminisces.

For generations, indigenous peoples shared their lands with other ethnicities and races, living mostly in harmony. They respected the natural boundaries and the laws set by their elders, understanding that land was not to be owned but cared for—a shared responsibility.

Their mutual respect reflected their reverence for nature’s rhythms, as reliable and uncontrollable as the rains and hurricane winds.

But everything changed when the settlers arrived in the early 1990s, after the civil war.

“At first, we weren’t worried about them. There was so much land for them to occupy, and they kept their distance, so we didn’t fear them,” Nelson recalls.

The settlers brought axes, rifles, saws, and an insatiable hunger for land—something the indigenous people didn’t fully understand until they saw the cattle herds and sawmills.

“There was a little mountain, a few days’ walk from Kiwas Tara, called Asanw. You could see monkeys moving for miles and miles, leaping from branch to branch without ever touching the ground—it was a dense forest,” Nelson reminisces.

“About 15 years ago, when we could still move freely in the hills, I went there. They had cut down the entire forest to make pastures. No monkeys, no jaguars, no tapirs were left. Only cows remained,” he laments.

The settlers’ growing presence forced indigenous communities to arm themselves to protect their lands.

“Some of us had hunting rifles, shotguns, and a few old war rifles, but those people (the settlers) have grenades. They’re well-armed, with radios and equipment—you can tell they have resources and support,” says Nelson.

He recounts how certain rivers and hills, known to have gold deposits, were once accessible to the indigenous communities, who managed to extract small amounts of gold with great effort for trade. These areas are now controlled by settlers, who operate heavy machinery to extract gold, polluting rivers with dynamite and gasoline-powered pumps.

Fish, animals, and birds have fled the territories, seeking refuge in deeper forests and rivers. This displacement means the indigenous people’s natural food sources are vanishing.

“In some communities, we tried to resist, but it’s impossible. If the police or military find you with a rifle, they confiscate it. But they don’t take the AKs from the settlers,” he complains.

Nelson points out that the settlers’ increasing violence, coupled with the impunity for their crimes, has eroded the communities’ ability to resist.

“Our ancestors had Councils of Elders. Now they’ve put in a Sandinista political secretary or a police officer to give orders,” he says bitterly.

“Some people now prefer to collaborate with them instead of opposing them. The police keep insisting on peaceful coexistence, saying peace is for everyone…” Nelson says, his voice trailing off in frustration.

In silence and without formal complaints, thousands like Nelson have been displaced, especially after 2018. They leave their homes with a sense of longing and the certainty that what was taken from them wasn’t just land—it was life itself.

“For us, living away from the nature of our territories isn’t living,” he states with quiet sorrow.

This report is part of the “Workshop and Master Classes” project by DIVERGENTES, supported by the Federal Foreign Office of Germany and the German Embassy in Costa Rica.