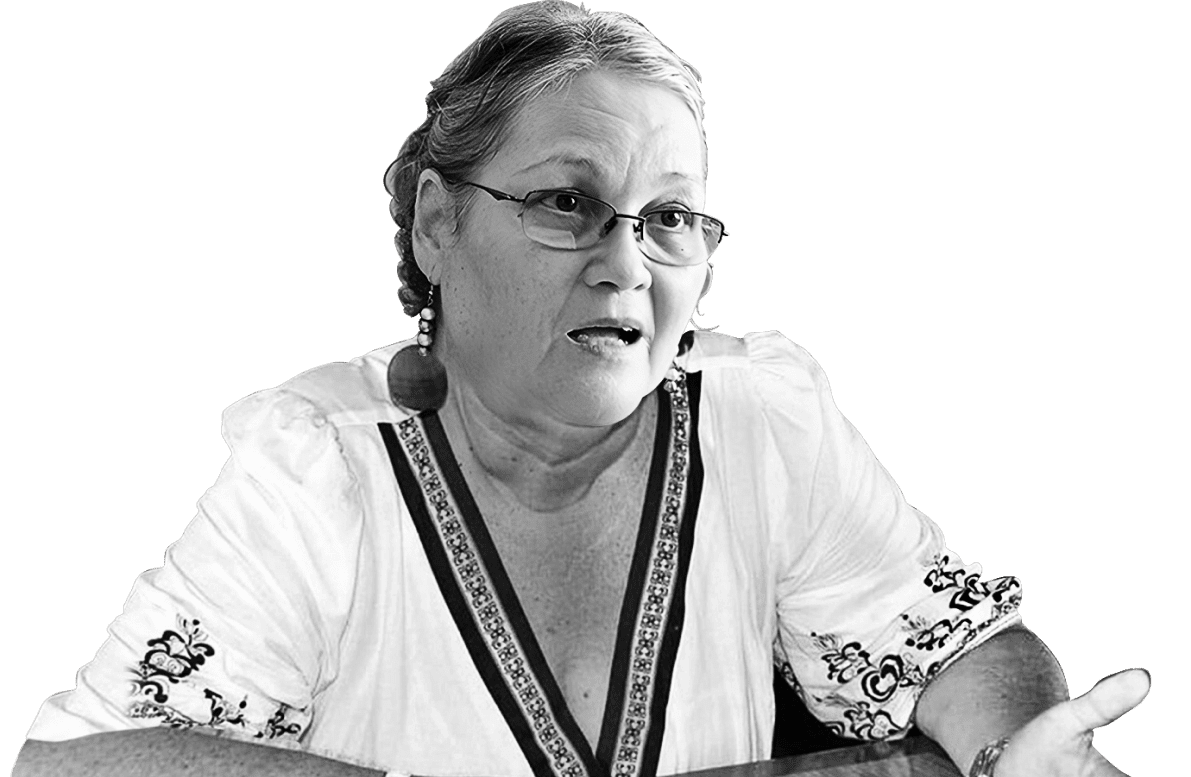

In 2018, during the “April rebellion,” which was later crushed by the Ortega regime, Martha, who had relocated to Costa Rica after the Sandinista persecution against her, to fully focus on her work with the Nicaraguan Network for Migration, expressed her concern and sadness over the impending bloodshed as the repression intensified.

“What I’ve gathered here, from my conversations with the Nicaraguan migrant community, is a great deal of uncertainty and fear about how this situation in Nicaragua will unfold. There is concern for their families; they ask me what’s next, if there will be a peaceful transition, they even ask who will replace Daniel Ortega. Let’s not forget that Nicaragua’s recent historical memory includes the overthrow of Somoza. It’s inevitable that comparisons will be made between two processes that share some common elements but also have marked differences,” she said in an interview with a Costa Rican television station.

“Dialogue is part of the solution. Someone decided to switch from rubber bullets to real bullets, to launch paramilitary repression. Those responsible, including those who pulled the trigger, must face a legal process. In a conflict of the nature Nicaragua is experiencing—where on one side there are stones, and on the other, bullets, on one side, words, and on the other, insults, where one side faces repression, and the other, social mobilization—there are no conditions to discuss the country’s major issues,” Martha warned.

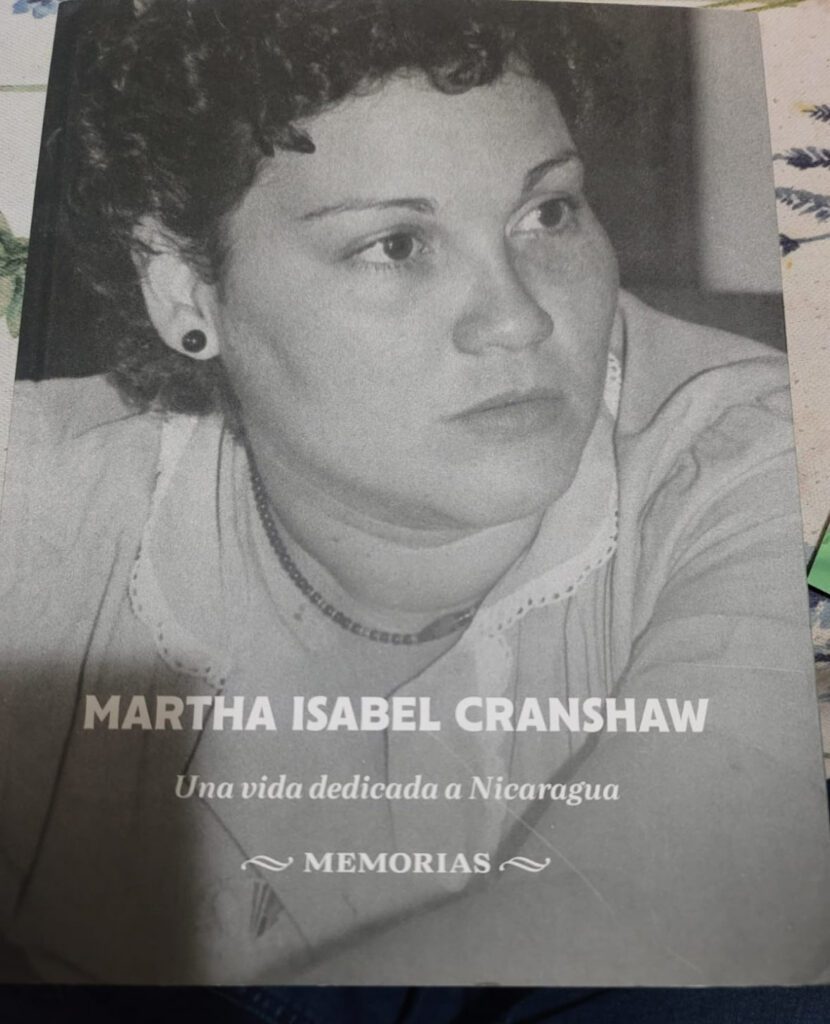

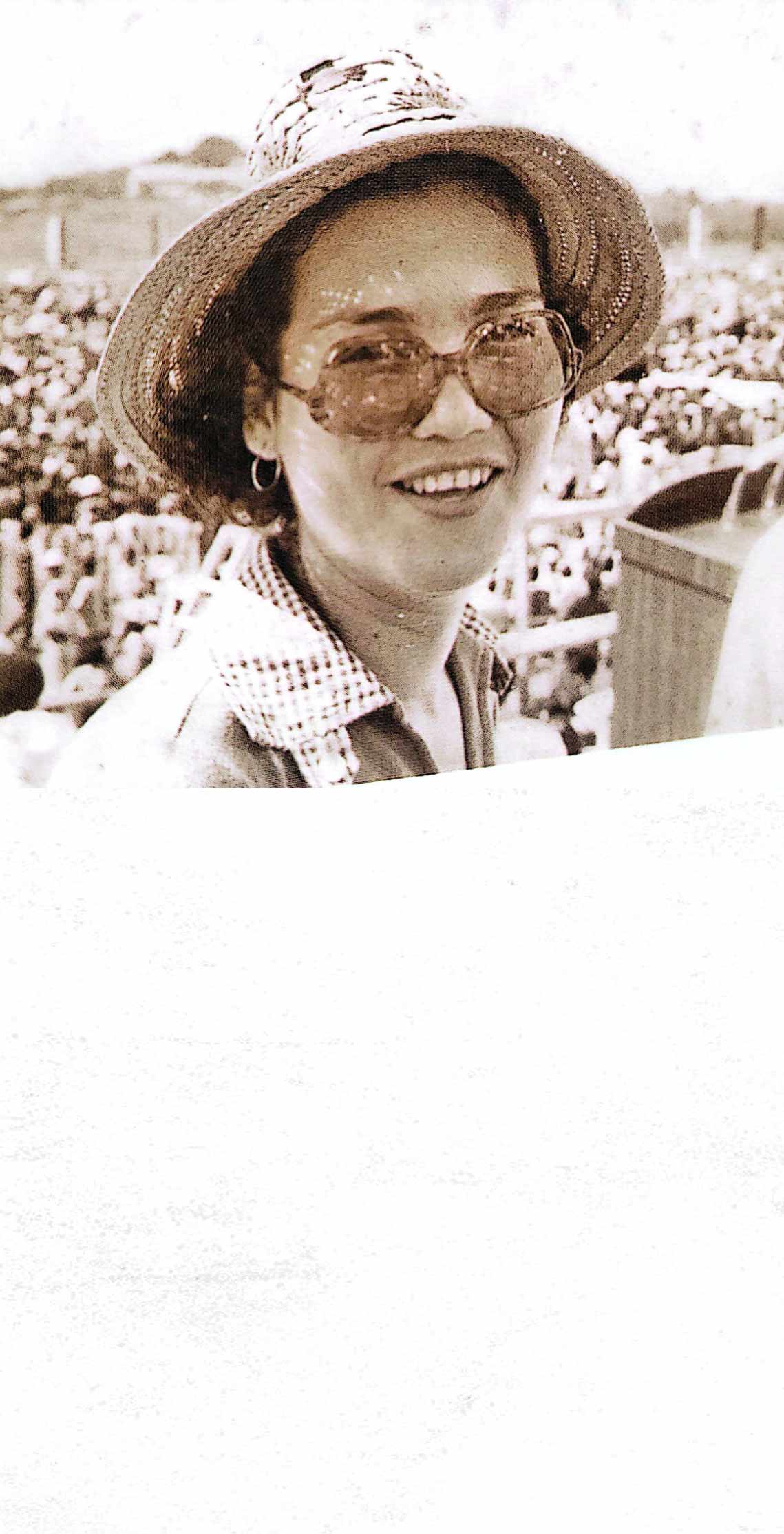

Born on January 16, 1955, Martha left this world just days before turning 65. Despite the Sandinista regime’s punishment for her social activism and the toll of Somoza’s prisons, Martha did not allow these events or the progression of her illness to define her days.

“She faced her illness with the same energy she faced her whole life, always concerned about her friends’ wellbeing, taking care of herself but always more concerned about others,” Quirós recalls.

“She was a very compassionate person, deeply concerned about the wellbeing of those around her, but especially her friends. She was always mindful of how people lived, what they were going through. She cared about their families and helped in any way she could to improve their situation,” reflects the activist.

Three months before her high school graduation from Colegio Asunción in Managua in 1972, Martha wrote a poem. These words, from a 17-year-old eager to take on the world—and more than that, to give her body, soul, and spirit to the social causes she fervently believed in—capture the essence of the person she would become during her life: