In mid-November, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) will appoint a new executive president for the next five years. Whoever takes the helm of the region’s main investment bank does so at a key moment in its history.

While only a small player compared to global institutions like the World Bank, CABEI plays a vital role in channeling billions of dollars into its five founding states: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Costa Rica. The bank says it accounts for close to half the development finance in Central America, one of the poorest parts of the Western hemisphere.

CABEI played a critical role during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the bank gave over a billion dollars in loans and grants to keep its founders afloat. With all of these states’ sovereign bonds rated as “junk,” CABEI has become a lifeline to international financial markets — and a key source of funding for the region’s authoritarian leaders.

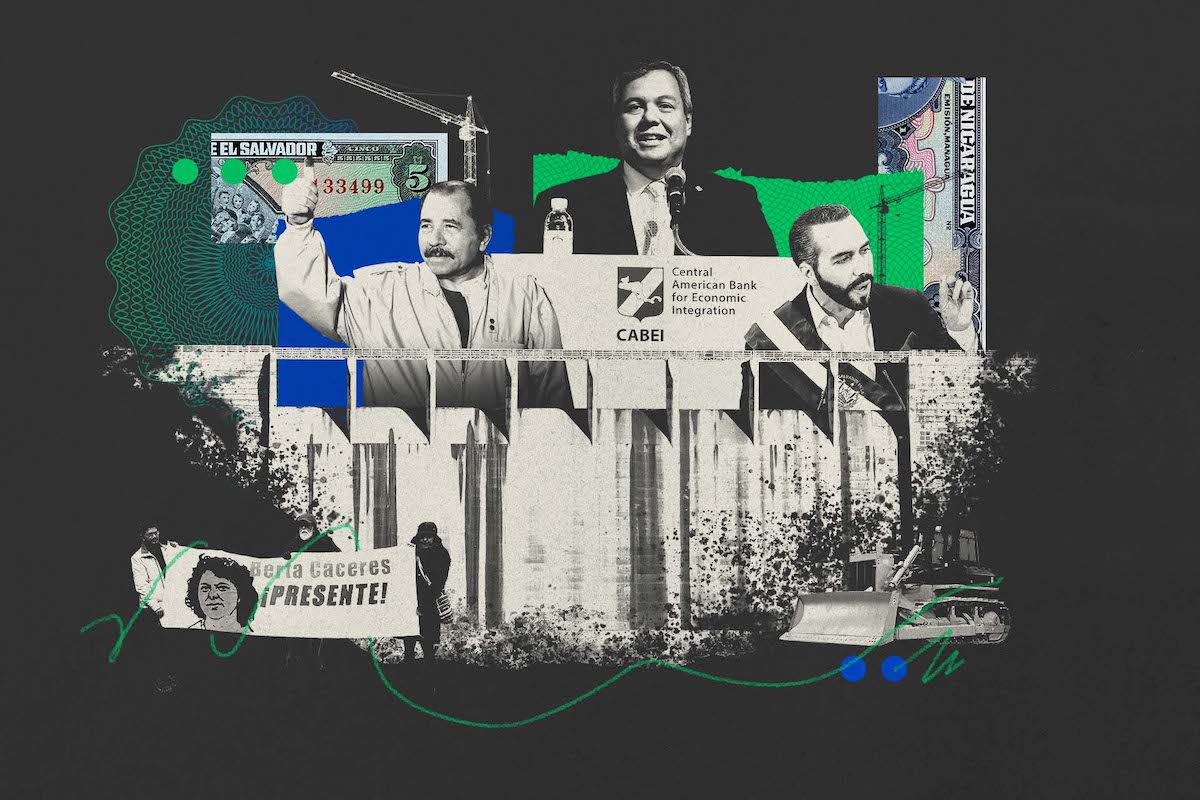

“It doesn’t matter what the politics are as long as poor people are getting services,” the bank’s outgoing president, Dante Mossi, said at an event in Washington, D.C., this year, as he faced criticism for providing funding to Nicaraguan dictator Daniel Ortega.

Recibe nuestro boletín semanal

“The bank is not a political model,” Mossi told the assembled crowd.

Others disagree.

CABEI has been criticized for giving billions of dollars to Central America’s authoritarian regimes — led by Ortega, President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, and the former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández. Now an investigation by OCCRP and partners can show the bank has funded projects that led to environmental destruction, and others where loans were diverted for corrupt practices or used to fund the pet projects of dictators.

Reporters spent more than a year investigating CABEI, combining open-source data with official investigations, leaked documents, and interviews with current and former bank employees. To get a clearer picture of the bank’s track record, reporters also compiled a database of more than 500 approved operations from the past quarter century. Together, they show how CABEI’s failures have enabled waste and corruption in one of the most unequal regions on Earth.

Reporters found the bank has backed at least 25 hydroelectric power plants in Central America since 1992, including several that were highly controversial. At least nine people who opposed these dams have been killed, while many more have faced harassment, threats, and bloody crackdowns for protesting.

The most high-profile was Berta Cáceres, an indigenous Honduran environmentalist who was assassinated for campaigning against the Agua Zarca dam. Internal audits show that CABEI ignored numerous red flags, performed scant due diligence, and continued to back the project after a protester was killed, their co-investors backed out, and the bank received dozens of complaints from indigenous communities — before selling off the loan in 2019.

In a case related to the Odebrecht scandal, one of the biggest corruption cases in Latin American history, reporters found the bank’s loans were used for bribes. In an ongoing corruption case in Costa Rica, they were seen as an easy source of cash by people charged with being part of an ongoing corruption case.

At least two former employees of CABEI, as well as people who have worked with the bank, said it has weaker controls on its lending than other development banks.

“It certainly doesn’t seem to me like there’s an audit procedure like the one the World Bank has,” said Carlos Acevedo, a former head of El Salvador’s Central Reserve Bank, which channels the development bank’s loans into the country.

Acevedo told reporters that CABEI operated like a “club of friends,” with politics prioritized over sound investments. “You approve a loan for me, I will approve a loan for you –– and that is how decisions are made,” he said.

This lax approach to lending appears to have worsened since Mossi took office in December 2018, according to sources within the bank and internal documents. Since then, CABEI has started giving out policy-based loans, a few-strings-attached type of financing that critics say is easily misused. Indeed, a third of the bank’s second-largest-ever public sector loan — $600 million to help small businesses in El Salvador survive the COVID-19 pandemic — was diverted to fund the president’s failed attempt to make Bitcoin a national currency.

Senior CABEI officials have raised concerns about the lack of transparency inside the bank. Late in 2021, nine directors wrote to CABEI’s governing board highlighting its deteriorating financial performance and accusing the bank’s administration of concealing information from them. Without action, the directors warned, CABEI would face “an eventual decline in financial health that the institution had been enjoying over the last decade.”

OCCRP’s analysis shows the bank’s finances have worsened since then, with profits falling and provisions for bad loans and costs rising. In a recent opinion piece published in Nicaragua’s Confidencial, CABEI’s former Costa Rican director Eduardo Trejos Lalli said the next bank president would face a difficult road ahead.

“Regardless of the election, the person who takes over will have to face not only the weak financial situation of CABEI, but will also have to carry out a thorough evaluation of the efforts carried out over the years by Mossi,” he wrote.

OCCRP made repeated attempts to seek comment for this story from the bank’s communications department and its head, but received no responses. Days before publication, the bank replied saying that it had not seen the messages and that, according to their freedom of information rules, they were only obligated to provide responses within two months.

However, the bank’s outgoing president, Mossi, responded to questions in multiple interviews and written comments. He said some projects undertaken before he joined CABEI in 2018 had been poorly conceived, but defended the bank’s track record, questioning why it has been singled out for supporting authoritarianism when other institutions also lend money in Central America.

“CABEI is not a political institution, we work with the member countries… We do not have the mandate to determine the form of government of any member country,” he said, rejecting the notion that the bank’s lending practices made its funding vulnerable to corruption.

“Central America is more sensible than other parts of the world,” he added in an interview with OCCRP. “I think the risks are totally miscalculated… I mean this is not Europe at all, but not Africa either.”

Cold War Legacy

CABEI was established in 1960, as the Cold War was shaping the fortunes of Latin America. Set up shortly after the U.S.-backed Inter-American Development Bank, CABEI, based in Honduras, was designed to give its members more control over their own development.

After a tumultuous 1980s amid Central America’s debt crisis, the bank expanded globally, incorporating new members such as Taiwan, Mexico, and Spain. With the recent addition of South Korea, CABEI now counts 15 members among its ranks, with assets of more than $13.8 billion.

Over the years, reporters found that CABEI has backed an array of projects that have been caught up in scandal. Several bear striking similarities, though they took place years apart.

Records cited in an investigation by prosecutors from a United Nations-backed anti-corruption commission show that scandal-plagued construction giant Odebrecht used millions of dollars from a CABEI loan to pay off state officials in Guatemala.

One of them, the commission’s records show, was former infrastructure minister Alejandro Jorge Sinibaldi Aparicio, who is currently facing trial in multiple corruption cases. OCCRP’s partner No Ficción obtained a copy of testimony that Sinibaldi gave to Guatemalan prosecutors, in which he

implicates CABEI in the alleged bribery scheme.

According to Sinibaldi’s account, CABEI’s former Guatemalan director was “fundamental” to the plan, which allowed Odebrecht to secure preferential terms in its contract to build part of a major highway. The former minister told prosecutors that the bank official both received bribes from Odebrecht and paid off other CABEI directors to approve changes to the contract.

Reporters could not independently corroborate all of Sinibaldi’s claims, including specific payments to CABEI officials. The former CABEI director that Sinibaldi named in his testimony, Oscar Humberto Pineda Robles, denied ever paying or receiving bribes, noting that his name has never appeared in any investigations or court cases related to Odebrecht.

“EVERYTHING MALICIOUSLY ATTRIBUTED TO MY PERSON BY THAT REPROACHABLE AND PERVERSE CHARACTER [Sinibaldi] IS, WITHOUT EXCEPTION, AN ABSURD LIE,” he wrote in an email.

Sinbaldi denied any involvement in Odebrecht’s bribery scheme, saying he had never even met Pineda. He also claimed the testimony obtained by reporters was a fake created to discredit him. “I categorically deny that I provided said statement,” he wrote to OCCRP, claiming it was fabricated “with the objective of generating conflict with important political actors, public officials and congressmen of Guatemala.”

Reporters confirmed the testimony’s authenticity with Guatemala’s public prosecutor’s office and two people close to the case. Reporters also obtained a copy of the amendments to the contract, which were approved by CABEI, redefining the project’s costs and securing Odebrecht a $73 million advance.

Sources at the bank who had knowledge of the case at the time said it was known inside the organization that officials had received payments related to Odebrecht. “It was known at that time that the director got money for the loan, and that many politicians got money for the loan, and that many employees in the bank got a lot of money for the loan,” said one of them.

Odebrecht, now known as Novonor, said it was unaware of any illicit dealings between its representatives and officials from CABEI.

Nearly two dozen people have been arrested or imprisoned in relation to Odebrecht’s scheme, and more are set to face trial. These include Sinibaldi, who is now facing trial over this and several other alleged corruption scandals from when he was in office. (Sinbaldi did not comment on the other cases.)

In another long-running Guatemalan corruption case, reporters found that CABEI has continued to finance the controversial Franja Transversal del Norte highway project even after it was engulfed in scandal.

In 2008, the bank approved up to $203 million for the project, which was to be built by Solel Boneh FTN, a subsidiary of major Israeli infrastructure company, Shikun & Binui. But Guatemalan government audits obtained by OCCRP show the highway was repeatedly cited for construction problems and failures in supervision, leading to multiple suspensions of work.

In 2017, a United Nations-backed commission and the Guatemalan Public Ministry presented findings that Solel Boneh and its holding company had bribed Sinibaldi while he was a congressman and, later, the country’s minister of infrastructure through a series of offshore companies.

Sinibaldi did not respond to questions about the Franja Transversal del Norte in time for publication. Neither did Solel Boneh, though it rejected many of the criticisms cited in the government audits as not its responsibility.

At least a dozen people have already been sentenced in relation to the corruption scandal, according to official sources. Despite the revelations, CABEI extended its loan for the Franja Transversal del Norte last year for another 12 months, until April 2023. As of late October, data on the bank’s website showed it had disbursed nearly $185 million.

Some 15 years after CABEI first agreed to finance the project, the highway remains incomplete. Even after the scandals and delays, government documents show Solel Boneh FTN remained the contractor as of August of last year — after CABEI had extended its loan for the highway.

Mossi, CABEI’s outgoing president, admitted to OCCRP that the Franja Transversal had faced “many issues,” but said the bank had agreed to extend the loan because it was a contractor to Solel Boneh that had been accused of corruption. “The Government and CABEI conducted the due diligence on the case, and concluded the behavior of the person was unrelated to the company,” he told OCCRP.

Mossi said he had inherited a raft of failing projects when he assumed his post in late 2018. “The bank made a lot of private sector loans that went bad,” he said. “I can tell you at least there were about two dozen really failed projects.”

Nick Rischbieth, the president of CABEI before Mossi, did not respond to requests for comment.

More recently, prosecutors in Costa Rica have investigatedcharged several government officials, who were in charge of administering CABEI loans to the state body that oversees road construction, of being part of another bribery plot.

According to evidence laid out in the case file, three executives at the agency CONAVI allegedly operated an influence-trafficking and bribery scheme to benefit construction firms working on several state-backed projects. (The judge is now deciding whether to proceed to trial.)

One was a bypass road around the capital, built by a consortium including Costa Rican construction firm H. Solís, which CABEI agreed to lend up to nearly $223 million. Wiretaps in the case file show the company’s owner and CONAVI officials discussing how they could obtain more money from the bank, which they saw as an easy source of cash.

In a wiretap included in the case file, one of thosee accused CONAVI officials, Carlos Solís Murillo, tells Mélida Solís, the head of H. Solís, that the bank is so lax you only need to “ask CABEI for permission” for a credit line and they “approve it right there.”

Both of them were taken into preventative detention in 2021 on suspicion of influence-trafficking and bribery. Prosecutors

did not respond to questions about the status of the case, or if they remain in detention. Investigations into almost 100 people and companies implicated in the wider bribery scandal reportedly continue. The Public Ministry told OCCRP that investigations continue into them and 77 other people, as well as 15 companies, for having received or offered bribes, influence trafficking, embezzlement, and fraud.

The case remains under investigation.

The people appear as defendants in the investigation.

79 natural persons and 15 legal persons are being investigated.

The crimes investigated are bribery, influence peddling, embezzlement, penalizing the corrupter and fraud.

It appears that CABEI has not disbursed any of the funds from the loan, according to data on the bank’s website. The bank did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did Solís Murillo or Solís.

Mossi said the corruption scandal had revolved around “the internal approvals in the Government of Costa Rica,” so it was not the bank’s responsibility.

From Projects to Policies

While CABEI’s questionable approach to lending stretches back years, reporters found the bank has adopted new practices since Mossi became president in late 2018 that have made it harder to monitor how governments use its funds.

Under Mossi’s leadership, CABEI started handing out so-called “policy-based loans,” a type of financing meant to help countries achieve big-picture goals, such as reducing poverty, rather than a specific project. Advocates say this more flexible approach allows governments to set their own priorities.

But critics say these loans are difficult to monitor and easily abused. Because the money goes straight into governments’ coffers, it’s difficult to know how it’s been spent. And because the funding isn’t for a specific project, it’s impossible to determine if it has been used effectively.

“We were financing projects, and now they are financing policies. And the policies are less and less clear in terms of what they’re going to achieve,” said Alberto Cortes, another of CABEI’s former Costa Rica directors.

According to correspondence obtained by reporters, several of CABEI’s directors opposed introducing policy-based loans, raising concerns about transparency and arguing it was against the bank’s rules to fund member states’ day-to-day expenses. Mossi compounded their worries by saying the loans wouldn’t need to be audited, they wrote.

“Since money is a fungible thing once it is deposited in the public account, it can be used for any type of current expenditure, and not for the destination or public policy originally given,” said the correspondence, obtained by Columbia Journalism Investigations (CJI).

“This is further exacerbated by problems of a lack of transparency, accountability and accounting systems in the budgetary control systems of the beneficiary countries.”

Mossi defended the bank’s use of policy-based loans, saying they had been implemented at the request of Costa Rica, with the board’s approval. When they became popular in the wake of the pandemic due to “the liquidity that ensued,” CABEI began trying to limit the use of these loans, he said. He also dismissed the notion, raised by some inside the bank, that he had started giving out policy-based loans to curry political favor.

“We did that out of need … for the countries and not the need for me to get reelected,” Mossi told OCCRP. “Many people saw my duty to serve the countries as a … sales campaign from my side to continue being president. I said, ‘That’s not my purpose.’”

Data published on CABEI’s website shows it approved 13 development policy-based loans between 2020 and 2022, totaling more than $2.5 billion. Some give specific goals, such as support during the pandemic or to combat climate change, but almost half give only vague descriptions, such as “Support Public Policy Actions and Development Results.”

They include a $250 million policy-based loan that would ultimately go to support Honduras’ notoriously corrupt state electricity company. Multiple studies have detailed corruption inside the National Electric Power Company (ENEE), with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace calling it part of “the country’s kleptocratic network” and the current government saying it was part of a major corruption scheme under previous administrations.

Finn Tarp, former director of the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, said it was highly problematic to give policy-based loans to organizations with a history of corruption.

“If there’s independent documentation of the behavior of such big companies, and then they still receive these massive capital injections … obviously, there’s something wrong,” said Tarp, who is now a professor of development economics at the University of Copenhagen.

ENEE did not respond to a request for comment. Mossi emphasized that the loan was not provided directly to ENEE, and noted that all of CABEI’s policy-based loans included anti-corruption clauses.

But even with other types of loans, reporters found that governments haven’t always used CABEI’s funds as intended. A third of the bank’s second-largest loan to date — $600 million to help small businesses survive the pandemic in El Salvador — was frittered away when it was needed most.

El Salvador’s economy was struggling when CABEI announced the loan in early 2021. The pandemic had sent the country’s GDP plunging nearly 8 percent the previous year, and many were suffering under strict lockdown restrictions. In a press release announcing the loan in April 2021, Mossi said it would benefit 4 million people, including business owners and families.

That July, CABEI gave the $600 million directly to El Salvador’s government, which was supposed to give it to local banks to lend to micro, small, and medium-sized companies. But only a fraction of the money— around $20 million — ended up being used as Mossi had described.

Instead, budget documents show the government diverted most of the cash to fund its own needs, allocating $425 million for “general state obligations.” Of that, over $200 million was earmarked for a pet project of El Salvador’s authoritarian leader, Bukele: making Bitcoin a national currency.

The self-styled “world’s coolest dictator” had announced his plan to make El Salvador the first country to adopt a cryptocurrency as legal tender in June 2021, a few weeks before CABEI signed off on the COVID-19 funds. Bukele argued that using Bitcoin would make it cheaper for people to receive vital remittances from overseas and help people without access to the banking system.

Others were less convinced, however, with Moody’s rating agency citing the plan as part of the reason it downgraded El Salvador’s sovereign bonds that year. Though the IMF also advised against the idea and the World Bank turned down the project over environmental and transparency concerns, CABEI supported Bukele’s plan.

“This is great news for the region,” Mossi said in a press release in June 2021, announcing the bank would provide “technical assistance” on how to implement the Bitcoin plan. The list of CABEI contractors shows the bank paid an IT company nearly $85,000 to conduct a study on the implementation.

Mossi said the study had advised that the legal and regulatory reforms required to make Bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador “were way beyond what the Government was willing to carry out.” He said CABEI had not intended for its pandemic support to be used for Bitcoin, and that language was included in the contract for the $600 million loan prohibiting it from being used for that purpose.

“Basically it says there’s a covenant in El Salvador, that no money from CABEI could be used to fund any Bitcoin activity. So we don’t, we don’t fund that,” Mossi said. When pressed on whether El Salvador had broken the terms of the loan, he agreed, but added, “Money is fungible.”

“We provided budget support so the government can use the money as they wish,” Mossi said.

El Salvador’s government did not reply to a request for comment.

Bukele’s Bitcoin experiment has been widely panned as a costly failure. A study by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research found that as of last year, fewer than one in 10 people who signed up for the government’s cryptocurrency app were still using it.

“The Bitcoin law was passed, but in reality, Bitcoin does not exist; Bitcoin is not legal tender,” said economist Cesar Villalona. “There is the law, and there is reality. The reality is that the country is still dollarized.”

Mossi agreed, adding: “At the end of the Bitcoin saga, it’s less than one percent of the Salvadoran economy, so…”

Financial Headwinds

These lax lending practices have come at a price. While CABEI’s credit rating remains high, giving the bank cheaper access to international finance, senior officials from inside the bank have raised concerns about its future financial stability.

In December 2021, nine of CABEI’s country directors wrote to its board of governors to express their concerns about its stalling performance and what they said was a lack of transparency around its investments.

In the letter, obtained by reporters, they raised “great concern about the management and financial parameters of the Bank and the serious concerns raised about its proper governance,” citing a plunge in CABEI’s profitability and the return on its assets since 2018, when Mossi became president.

Until recently, the directors noted, the bank’s growing loan book and assets had indicated it was in a strong financial position. So they were caught by “surprise,” they said, when the October 2021 figures showed profits had slumped to $83.6 million, down from $223.5 million in 2018.

The directors accused the bank’s administration of concealing information from them, so they couldn’t make informed decisions on whether to invest in “operations that also present serious deficiencies in their foundations.”

“Management has insisted on various practices aimed at preventing the necessary inputs from being available so that the directors can adequately exercise their functions,” they wrote. Without action, the directors warned CABEI faced “an eventual decline in financial health that the institution had been enjoying over the last decade.”

Mossi disputed the directors’ concerns, saying the board of governors had rejected the points raised in the letter. CABEI’s finances were “better than ever” and the bank is “doing fantastically” he argued, pointing to its 2020 capital increase from $5 billion to $7 billion.

CABEI’s profits have fallen since the directors voiced their alarm, with net financial income down more than 6 percent in the six months through June 2022 compared to the same period a year earlier, the most recent figures that are publicly available. Acevedo, the former head of El Salvador’s central bank, reviewed CABEI’s accounts and agreed the fall was “striking,” saying it warranted a closer look at how the bank is being managed.

Part of the issue appears to be due to the deterioration of the bank’s loan book, with the provision for public sector loan losses up nearly 40 percent from a year earlier in June 2022.

In a statement released a few months later, S&P’s ratings agency also raised concerns about the economic outlook for Central America, warning of “weaker asset quality” in the region.

Meanwhile, CABEI’s level of risk-adjusted capital — a key measure of financial stability referenced by the directors in their letter — also declined, sliding to 14 percent by June 2022, down from 15.7 percent at the same time the previous year.

As CABEI’s profits have fallen, its costs have risen, with spending on salaries and employee benefits up over 13 percent in the first half of 2022 compared to the same period a year earlier.

Ottón Solís, another of CABEI’s former Costa Rica directors, said he complained about the bank’s culture of lavish spending when he was still working there in 2018, but the governors quashed his attempts to rein in expenses.

In an interview with Spain’s El Pais newspaper after leaving his post, he described how directors were paid $20,000 a month tax-free, received luxury gifts, had discretionary use of vehicles and unlimited first-class flights in the region, and received holiday bonuses. According to his calculations, CABEI’s spending relative to its assets was triple that of the World Bank and the IDB.

“It looks like the bank of an oil economy in the Persian Gulf,” he told the paper. “These excesses are incompatible with CABEI’s development goals and with the income levels of the majority of the region’s inhabitants.”

Mossi admitted CABEI had seen “the cost of doing business increase in absolute terms” in recent years, but overall he described the bank as “low cost” and “highly efficient.”

Despite the financial headwinds it is facing, CABEI appears confident in its future. In its June 2022 financial statement, the bank said it had changed its accounting methodology to hold less money in reserve against default. The move allowed the bank to release nearly $133 million, boosting its income for the period to just over $250 million and improving its financial metrics.

But a former CABEI official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid professional repercussions, said the change was just a way to make the bank look better on paper.

“It is not cash income, it is only an accounting maneuver which increases profits and allows the bank to improve its capital base for lending,” they said.

Funding Authoritarianism

It was a blustery day in early May when Nicaraguan lawyer and political activist Juan Diego Barberena led a small protest against Mossi’s re-election as president outside CABEI’s offices in Costa Rica’s capital.

Berberena claimed CABEI has become the main funder of Nicaragua’s oppressive government under Mossi, whom he accused of handing out loans indiscriminately to curry favor with Ortega and Central America’s other authoritarian leaders.

“Mossi’s strategy was to obtain the support of the majority of the founding partners of CABEI through the indiscriminate and discretionary granting of loans in order to be reelected,” he told OCCRP. “It’s an issue of transparency and accountability.”

CABEI has drawn a growing chorus of criticism for funding Central America’s authoritarian leaders, particularly Nicaragua’s strongman president, Ortega. Earlier this year, Mossi appeared at a debate in Washington, D.C., where he was forced to fend off repeated accusations that he was propping up the country’s brutal regime with loans to win political support.

The day after the debate, the chairmen of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee and House Foreign Affairs Committee wrote to the bank’s four other founding members asking them to increase scrutiny and transparency of its funding for Nicaragua. CABEI was also named in legislation introduced in the U.S. Senate in June, which called for the State Department to restrict investment and loans benefitting the government of Nicaragua.

“In recent years, the United States has taken steps to increase the scrutiny of and curtail funding from multilateral institutions that would directly benefit the Ortega-Murillo regime,” said the letters. “We urge your government to pursue similar policies with regard to CABEI lending.”

OCCRP analyzed historical data about CABEI’s lending available on its website dating all the way back to the 1960s. It showed that over the decades, most of the funds the bank approved were for Costa Rica — generally seen as Central America’s most democratic country — including in the years after Mossi became executive president in December 2018.

In the three years before Mossi became president, Costa Rica also received the highest amount of disbursements. But this changed after 2019, when El Salvador and Nicaragua received the greatest share of the bank’s funds. In both cases, the amount of money that CABEI gave to each country almost doubled from 2018 to 2021.

The peak of the disbursements to both countries was in 2021, when Ortega was accused of carrying out a wide-ranging crackdown on journalists and civil society political opponents in the run-up to national elections. In El Salvador, CABEI even approved loans for the police and defense ministry as Bukele was pursuing his controversial territorial control plan.

Bukele’s state of exception

It was a scene that one civil rights group compared to the darkest days of El Salvador’s civil war: Soldiers in full battle fatigues occupied the floor of parliament in a bid to pressure lawmakers to back the president’s new security plan.

Troops invaded the building in February 2020 after opposition lawmakers refused to take part in a vote to approve a $109 million loan from CABEI for phase three of President Nayib Bukele’s so-called “territorial control plan,” aimed at combating widespread gang violence across the country. Though the loan was not approved that day, it was ratified the following year.

The loan, which was described as for “citizen security,” allocated millions of dollars for El Salvador’s police and defense ministry, including funds earmarked to buy surveillance equipment and a helicopter.

“Development banks shouldn’t fund a police so abusive as El Salvador’s,” said Juan Pappier, Americas deputy director at Human Rights Watch, noting that “throwing people in jail massively and abusively should be enough reason for CABEI to put these funds on hold.”

In March 2022, Bukele imposed a “state of exception” that suspended many civil liberties across El Salvador.

Since then, the government has detained more than 72,000 people and human rights groups have documented a litany of abuses by police and the military, from arbitrary detentions to the killing and torture of people in custody.

Though CABEI has not yet disbursed loans for the second and third phases of Bukele’s control plan, which come to $200 million, the bank is still backing him. In mid-2022 — just a few months after El Salvador’s government imposed the state of exception — bank resolutions show both loans were extended for a year.

Mossi said the bank agreed to the loans because they were to fund “a citizen safety program that includes a variety of activities” and they would be “closely monitored.”

“CABEI has a negative list of items we cannot finance, and we do respect that list,” he said. “El Salvador’s security program was carefully monitored to ensure that list was respected.”

Acevedo, the former head of El Salvador’s central bank, said the increase in CABEI’s lending to Nicaragua and El Salvador was “striking” — and potentially dangerous.

“This entails reputational risks that can eventually translate into financial risks,” he said.

Asked about the rise in lending to Nicaragua and El Salvador, Mossi said each country’s demand for resources “is linked to their internal governance and electoral cycles, their capacity to implement projects, and the appetite for our loans,” which had increased during the pandemic. He said CABEI had no political agenda.

Faced with financial pressures and political headwinds, whoever becomes CABEI’s president does so at a critical time for the bank. After receiving more than 240 applications, the bank has whittled it down to a shortlist of three and will announce the winner on November 17.

Among the candidates is CABEI’s current executive vice president, Guatemalan economist Jaime Roberto Díaz Palacios, who has assumed many of Mossi’s functions in the run- up to the president formally stepping down in December.

Late in October, Mossi wrote to the bank’s governors, arguing that the move to give Díaz Palacios control of CABEI while he was running to be president was illegal, and raising questions about the impartiality of the selection process.

“The idea that the Board transferred functions from the Executive President to the Vice President in an illegal manner, and now he is on the list of candidates, suggests a flaw,” he wrote to CABEI’s board of governors on October 20.

Mossi also called out the official candidate of Costa Rica for holding meetings with the board of directors in Guatemala, saying it “caused concern about the neutrality of the entire selection process.”

Looking back on his time at the bank in conversation with OCCRP, the outgoing chief executive said he was happy with his legacy.

“I was a well-paid executive at the World Bank living in Washington, D.C.,” he said. “I took this challenge, and I think I did make a difference.”

Mariana Castro, Andrew Little, and Madeline Fixler are reporting fellows for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School.