The lifestyle Samir leads is one of such severe isolation that it even prevents him from attending church or visiting a park. This nearly 60-year-old journalist lives amidst the uncertainty of exile in Costa Rica, never losing hope that he’ll one day return to Nicaragua to retire.

Sayda, a 39-year-old business administrator, treasures a small window in her tiny room provided by her employers in Spain. From there, she admires the beautiful scenery of Seville, the city she’s called home since 2019 but knows only through photographs she looks at on her phone, unable to explore it in person.

Ernesto, a 32-year-old construction worker facing his second exile in Virginia, USA, decided to erase his customs, celebrations, soccer games, and friend gatherings from his mind and vocabulary.

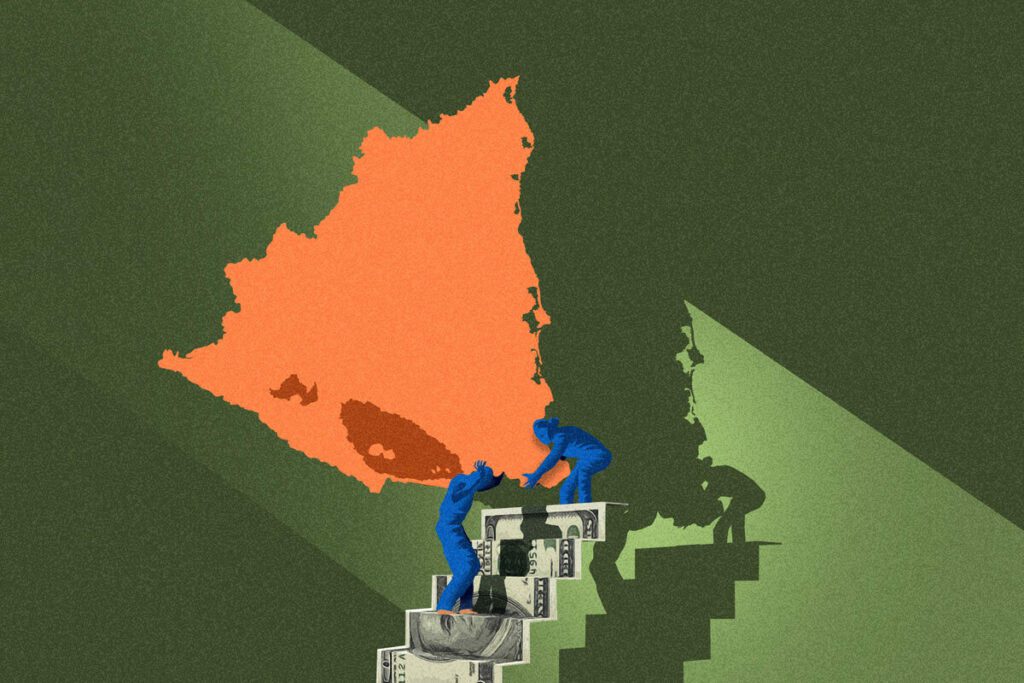

These are just some examples of the sacrifices made by many of the nearly 900,000 Nicaraguans who have migrated due to the sociopolitical crisis of 2018. Their goals in leaving: ensuring their earnings in dollars or euros cover their expenses, support family back in Nicaragua, and, in many cases, pay off debts incurred from the journey.

Costa Rica, a Central American country with first-world prices

Samir has turned solitude into his ally. Going to church on Sundays and then taking a walk in a park or mall requires at least $4 for the bus fare and an additional $6 for a drink or soda, plus a piece of bread to eat until he returns home.

“Life in Costa Rica is very expensive. Salaries aren’t enough to live on. Half of my income goes toward household expenses and personal hygiene products. If I went to church, I’d have to adjust the other half that I send to Nicaragua to cover my family’s expenses there—my wife, daughter, granddaughter, and a small amount for my father. So going to church is a luxury I can’t afford,” he says.

Samir has been affected by the depreciation of the Costa Rican colón. When he arrived in July 2021, the $1,000 he earned in his job equaled 700,000 colones. By 2024, that same $1,000 amounts to only 500,000 colones, almost the cost of renting a modest home.

Reading and talking on the phone with family and friends helps him endure confinement, which is permanent, as he works online for a media outlet Monday through Friday.

Despite the severe limitations he faces, he feels grateful he can continue practicing journalism in exile, a profession that would land him in prison in Nicaragua. “It’s the only thing I know how to do, and here in Costa Rica, the job opportunities for migrants are mostly in construction and security work—jobs I’m not physically up to at my age,” he says.

The drastic savings measures adopted by Samir are the daily reality for most of the nearly 900,000 Nicaraguan migrants, mainly concentrated in Costa Rica, the United States, and Spain.

With the assistance they send to their families, they’ve spurred significant growth in remittance flow to Nicaragua, which has risen from $1.5 billion in 2018 to over $5 billion according to estimates for the end of 2024.

Those who lost their lives seeking to be part of the remittance flow

According to a count by La Prensa, from January 1 to October 22, 2024, at least 134 Nicaraguan migrants lost their lives in the United States. Some perished during the journey, while others died after arriving. The main causes of death were traffic accidents, workplace incidents, and illnesses. At this rate, the death toll will surpass that of 2023, when at least 148 Nicaraguans died, mostly in the United States, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Spain.

These deaths are of no interest to the regime. In fact, it has never addressed them and has made it clear, through its own officials, that only the money sent by migrants matters.

“We believe that this year we’ll once again reach, or perhaps exceed, $5 billion in remittance income. It’s an important factor for the economy and, most importantly, supports consumption, as low-income families receive it, which is beneficial,” stated Ovidio Reyes, President of the Central Bank of Nicaragua (BCN) and economic operator of the dictatorship, in a recent interview with a Sandinista propaganda outlet.

As Reyes announced, by the end of 2024, Nicaragua will surpass the $5 billion mark in remittances. By August, $3.4 billion had already been received, and with a current monthly trend of over $400 million, plus the usual increase in December, the target is assured.

The significance of their share in GDP

However, the total amount of remittances isn’t what matters most, warns economist and exiled former political prisoner Juan Sebastián Chamorro. Chamorro points out that while the annual remittance amount has surged—with a triple-digit increase between 2018 and 2023—some countries receive even higher sums. What truly matters is the proportion of GDP that remittances represent for the country.

“The GDP proportion relates to the size of the economy, and this is extremely important. To me, that’s the most relevant figure because it’s adjusted to the size of the economy and the population. For instance, Mexico’s remittances ($63.3 billion in 2023) are many times Nicaragua’s, but Mexico is a larger economy with a population of around 130 million, while Nicaragua’s is under seven million. There’s no comparison,” Chamorro explains.

Chamorro’s point is backed by reports from the Central American Monetary Council (Secmca), showing that in 2018, when Nicaragua received $1.5 billion in remittances, they represented 11.53% of GDP. Last year, that figure rose to $4.6 billion, equal to 26.14% of GDP. In just five years, remittances’ share of Nicaragua’s GDP has doubled.

While the migration crisis isn’t unique to Nicaragua, no other country in the region has seen such a drastic increase in this income source. According to Secmca, Panama received the least remittances in 2018, at $456 million, representing 0.7% of its GDP.

Among the countries receiving the most, Honduras led with $4.8 billion, which equaled 20.29% of its GDP. By 2023, Honduras received $9.2 billion, increasing the GDP proportion to 26.68%—the highest in the region, slightly above Nicaragua’s.

Between 2018 and 2023, Honduras saw a 6.39 percentage-point increase in remittances’ share of GDP, while Nicaragua’s jumped by 14.6 points, placing it close to overtaking its northern neighbor. This could happen by the end of 2024, with the proportion estimated to reach around 30%.

Over five years (2018-2023), Nicaragua has surpassed Guatemala and El Salvador as the economies most reliant on remittances. Migration in these countries, along with Honduras, is largely driven by gang violence and poverty.

A 2023 World Bank report listed Nicaragua among the top five countries worldwide where remittances represent the highest percentage of GDP: in Tajikistan, it’s 48%; Tonga, 41%; Samoa, 32%; Lebanon, 28%; and Nicaragua, 26%.

Nicaragua’s economy expands, fueled primarily by labor exports

According to research by Manuel Orozco, director of the Migration, Remittances, and Development Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, Nicaragua’s economy will maintain stable growth due to the economic relief from remittances, as around 60% of households rely on these resources, benefiting approximately 1.05 million Nicaraguans.

Chamorro, however, warns of the dangers of an economy so dependent on remittances, as countries can’t base economic growth on the export of human beings.

“Their argument is that this migration doesn’t harm the economy because it’s unemployed labor leaving—excess labor that Nicaragua’s job market couldn’t absorb. But that’s a ridiculous argument because what’s left is a resource that the country invested heavily in, from birth through graduation or career completion,” he explains.

Chamorro adds that this human capital, in which Nicaragua invested to prepare, is now working as laborers in Costa Rica or Spain or operating machinery in the U.S. or in any job available where they’re based.

“This is ultimately a loss that’s likely permanent for the sending country. It’s not a smart strategy for sustaining economic growth, as it means living off human capital that isn’t being replaced. Eventually, the country will run out of this capital and the income generated from remittances,” Chamorro warns.

Remittance flow will not continue growing

Experts suggest various reasons the remittance flow won’t keep growing at recent rates. The distance, loss of loved ones, and paying off debts are factors that could slow remittance growth.

Sayda agrees. She plans to stop sending remittances soon. Initially, she sent $500 monthly, but after clearing an old debt last year, she now sends only $300 to cover her teenage son’s expenses. He’ll graduate high school this year, and she hopes to have him with her in Seville before Christmas.

Since arriving in Spain at the end of 2019, she’s spent her free days confined indoors. Going out incurs costs for transport and even food—luxuries she couldn’t afford initially due to the debt she left in Nicaragua.

Now that her debt is paid off, she’s saving what she used to send for loan payments. When her son arrives, she’ll need to rent a room and buy a bed and a TV, so he won’t feel the adjustment too harshly.

“Since I came to this country, the only new things I’ve bought are shoes. I only spend on deodorant, toothpaste, and soap. At work, they advise against wearing too much makeup, so I’ve gotten used to not buying any,” she shares.

“I left Nicaragua in search of a better life because I hadn’t had steady work for years, and my debts were overwhelming. But I never imagined it would be this hard. People say, ‘They pay in euros there,’ but they don’t mention you also have to spend euros, nor how expensive things are here. For now, I’m just holding onto the hope of legalizing my immigration status to get a better-paying job,” she says, hopeful.

According to Manuel Orozco, the length of time a migrant has been abroad affects how much they send back. Based on his research, Nicaraguans who left before 1999 send around $125, while those who left between 2000 and 2017 send $224. Meanwhile, the average remittance of those who migrated starting in 2018 is $450.

“In other words, migrants who’ve been away for over six years could reduce their average remittances by about 20%,” Orozco explains.

The Ortega-Murillo regime benefits from remittances

While nearly 900,000 Nicaraguan migrants sacrifice to send remittances, the Ortega-Murillo regime reaps the benefits of this migration tragedy.

“The regime benefits because it means resources. It’s not direct—remittances don’t go straight into government coffers. But they do increase VAT (Value Added Tax) collections, as remittances fund consumption. This consumption often includes imported goods, so a significant portion of the remittances ends up back where items like clothes, phones, or refrigerators are made,” Chamorro explains.

“Politically, the regime also favors migration as it gets rid of opposition members, who are often the ones leaving. This acts as a pressure release valve, reducing political tensions,” he notes.

Host country’s economy impacts remittance flows

The Central Bank of Nicaragua’s (BCN) remittance report shows that in 2017, the average remittance entering Nicaragua through banks and specialized agencies was $188.5 per transfer. By the first quarter of 2024, this rose to $268.5.

The World Bank confirms that the economic performance of the migrants’ host country influences remittance growth. In 2023, the strength of the U.S. labor market boosted remittances, benefiting Nicaragua particularly.

The World Bank noted that in 2023, remittances to Mexico—the region’s largest recipient—increased by 9.7%, while in Nicaragua, they surged by 45%.

Many migrants also incur debt to finance their journeys. Numerous Nicaraguans who entered the U.S. irregularly face bond payments that force their families to go into debt.

Ernesto’s migration struggle

This is Ernesto’s case: over the next two years, he’ll need to keep sending $500 monthly to Nicaragua to support his parents and repay the $5,000 they sent him to cover the bond from his detention in a U.S. immigration facility, where he spent months after crossing the border. Additionally, he sends $250 to Costa Rica for his seven-year-old child’s support.

Ernesto is on his second exile. The first was in the wake of Nicaragua’s 2008 municipal elections. With several family members in the Liberal Party and his work at polling centers in a municipality in the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCS), where he’s from, retaliation forced them to flee to Costa Rica. There, he finished high school and, like most Nicaraguans in Costa Rica, ended up working in construction.

Life was fairly stable until the effects of COVID-19 and Costa Rica’s migration crisis drove prices up, and his salary couldn’t cover expenses. After a rough patch in Nicaragua with his parents, he decided in January 2024 to pursue the “American dream” in the U.S., joined by three cousins and a group he found through social media, which helped them support each other and save on the journey.

Now, he works in an industrial cleaning role at a sauce factory, safe from the freezing winter temperatures of the U.S. area he lives in. His hours are 4 a.m. to 3 p.m., Monday to Friday. On weekends, he looks for construction work, which, after rent and expenses, lets him make up the $750 he sends each month.

“In the U.S., you have to limit yourself and sacrifice a lot. Working from 4 a.m. to 3 p.m. is tough. Also, on weekends, while others go out, visit friends, or rest at home, we keep working. But it’s the only way to get ahead and hopefully save enough to someday return to be with my family,” says Ernesto.

“Here, the kinds of celebrations we have back home don’t exist. Here, life is all work. But the hardest part was leaving my son, knowing it’ll be years before I see him again. It breaks my heart when he asks when I’ll visit to take him to the park,” he adds with a touch of nostalgia, hoping his political asylum will be approved so he can visit or perhaps bring his son to live with him.