Nicaragua was the last country in Central America to provide the vaccine against Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) from public health to girls and teenagers. Although the Ortega-Murillo regime has announced it with enthusiasm, it is an obligation that has been pending with women for years, says Maggie, a specialist in sexual and reproductive health, who requested anonymity.

“Women, girls and teenagers have been vulnerable all this time without prevention actions against HPV, the main cause of cervical cancer, despite the fact that this virus is the one that causes the most women’s deaths in Nicaragua,” says the specialist.

Although the country’s health centers and hospitals perform cervical cytology tests, mostly known as Pap smears, to detect the virus, the most effective prevention strategy against HPV is vaccination, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Nicaragua does not include the HPV vaccine in its immunization plans

The Nicaraguan State was under the obligation to guarantee this vaccine at least since 2020, following the approval of the “Global Strategy for Accelerating the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Global Public Health Problem and its associated goals and targets for the period 2020-2030” by the WHO at the 73rd World Health Assembly.

Recibe nuestro boletín semanal

The strategy was a wake-up call to all those countries, such as Nicaragua, that had not included the vaccine in their vaccination plans, despite the high numbers of hospitalizations and deaths from cervical cancer, mostly caused by HPV.

The vaccine had been introduced in the Americas since 2006 and specifically in Central America since 2008. Until this year, Nicaragua was the only country in this region that had not yet been vaccinated and also the country with the highest number of deaths from this disease per inhabitant.

According to the WHO, in order to eliminate cervical cancer, countries must reach and maintain a number of less than 4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year.

In Nicaragua, the rate of cervical cancer was 21.4 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2021, according to a profile by the WHO in that year to analyze the beginning of the implementation of the strategy, which at that date had not yet been implemented.

In addition, the number of women dying from cervical cancer has increased since 2019. According to the Ministry of Health’s National Health Map of Nicaragua, 208 women were reported to have died from a malignant cervical tumor in 2019; the figure has progressively increased to 270 women dying in 2022.

And although the late inclusion of the HPV vaccine to the Annual Immunization Plan (PAI) can be considered part of compliance, it is still a long way from fully guaranteeing its obligations to the health of women, girls and teenagers.

Recommended populations not included in Minsa’s plan

According to the plans announced by Minsa, the objective is to apply the vaccine to 300,000 girls and teenagers between 10 and 14 years of age, from November 6 to January 15, 2024.

However, its coverage is still quite limited for the population it is obliged to immunologically protect.

In addition to the one- to two-dose schedule for girls aged 9 to 14 years, the WHO recommends the same schedule for teenagers and women aged 15 to 20 years, and two doses, six months apart, for women over 21 years.

Only the female population under 19 is more than 1.3 million, according to data from the National Institute of Development Information (Inide). In other words, its current target only covers 23% of the population that should be vaccinated. Currently, Minsa has not reported any plans to expand the target population.

The WHO also emphasizes protecting “as a priority” women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and immunocompromised women, as they are up to six times more likely to develop cervical cancer.

In 2022 there were 6567 people on Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), 1129 new cases of HIV and 145 pregnant women with HIV, according to the National Health Map of Nicaragua. However, this data specifies the population of women, apart from pregnant women.

“Vaccination of secondary targets, such as children and older women, is recommended whenever feasible and affordable,” concludes the WHO.

There is resistance to the vaccine

In addition to providing the vaccine to key populations, another obligation of the Nicaraguan state is to “collaborate with the education sector and community members, in particular to address the lack of trust in the vaccine”. In other words, to inform girls, teenagers and their parents about the importance of the vaccine in order to guarantee its application.

This instruction was briefly transmitted through the official channels of the Ortega-Murillo regime and with some workers of the Ministry of Education, but not with the rigorousness urged by the WHO.

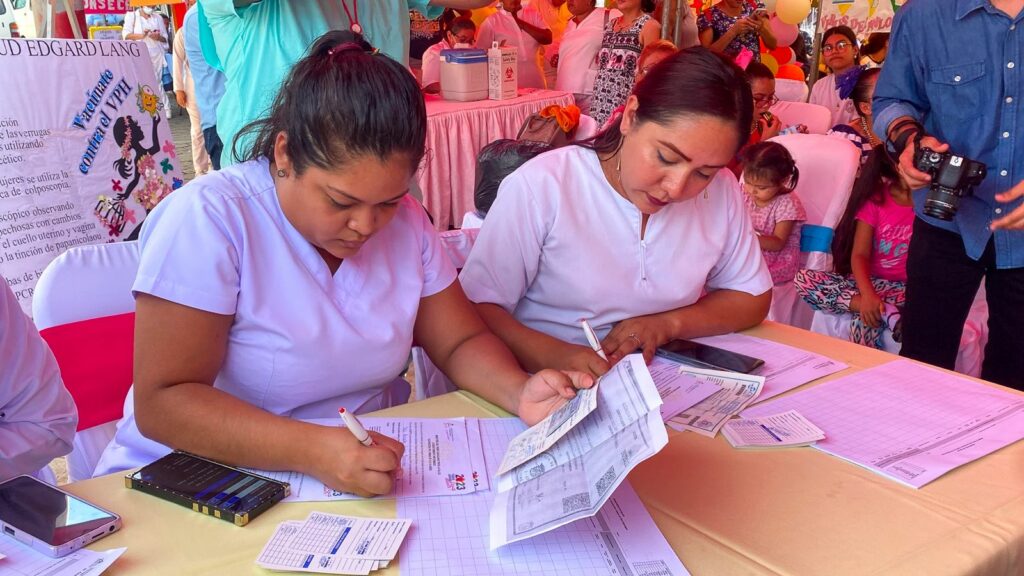

As of November 26, 185,202 doses of HPV vaccines have been applied to girls between 10 and 14 years old, which means 62% of Minsa’s target population. However, there has been a lot of resistance from the population, says Maggie, a specialist in sexual and reproductive health.

This is precisely because the Ortega-Murillo regime has never addressed this problem in a preventive manner and there are many myths and misinformation among the population about HPV and other sexual health issues. Comprehensive sexual education in Nicaragua is non-existent.

“This is due to a lack of truthful, scientific and non-judgmental information to girls and boys about sex education. Many mothers do not allow their girls to be vaccinated because they say ‘she’s not old enough yet’. Many mothers say ‘what’s the point of getting that vaccine if my girl doesn’t have sexual relations’.

That’s where sex education starts, so that I can make decisions as a family member and guide a teenage girl,” she says.

“People are suspicious because it is something the government has never talked about. Many people are only now realizing that vaccines exist, that there is a way to prevent the virus and that it is more effective if it is done from childhood. Why is there resistance? What is not made known creates fear and insecurity. In other countries, the vaccine has been applied for 20 years”, she adds.

Vaccines are unafordable

To guarantee the prevention of HPV infection, 90% of the population of girls and teenagers under 15 years of age should be vaccinated, according to the WHO strategy. In addition to the data provided by Minsa on recently vaccinated minors, the number of women and girls vaccinated in the private health sector is unknown, but it is clearly small, says Maggie.

This is because the costs of the vaccine in private clinics “are inaccessible for Nicaraguan families”, says the specialist. Vaccine prices vary from US$100 to US$150 per dose.

In the case of minors, it is recommended to apply two doses with a period of six months for the vaccine to be effective; and in adult women, at least three doses are recommended to ensure adequate protection.

In other words, the costs to access the complete vaccine scheme range from 200 dollars to 450, in other words, between 7300 córdobas and 16,425, depending on the number of doses and the prices established by the clinics.

In a country where the minimum wage is $213 per month according to the Ministry of Labor, access to vaccines is a luxury that many citizens cannot afford, even if it costs them their health. To reduce these inequalities, it is necessary that the Ortega-Murillo regime apply the vaccines in their entirety to the recommended populations, and not just to a small group.

Sexual and reproductive rights of minors are not respected

Maggie also points out that the health of teenage girls has been a historically neglected need by the Ortega-Murillo regime, and greater efforts than vaccination are needed to respond to the vulnerabilities experienced by minors, such as sexual violence and child and teenage pregnancies.

A WHO multicenter study showed that the prevalence of the HPV infection is higher in sexually abused girls or if there is an early pregnancy.

“There is no prevention of teenage pregnancy and other sexually transmitted diseases. The HPV vaccine is only a part of a big problem that has never been addressed. In Nicaragua there are girls giving birth and that is the State’s responsibility. Girls’ sexual and reproductive rights need to be prioritized and should not be seen separately,” says Maggie.

There are currently 44 countries in the Americas that include the HPV vaccine in their annual vaccination plans, according to the Pan American Health Organization. The first country in the Central American region to include the vaccine in its plan was Panama in 2008, followed by Belize and Honduras in 2016, Guatemala in 2018, Costa Rica in 2019 and El Salvador in 2020.