Everything was part of a show. From the political actors of the Ortega regime to the then-allies in the private sector, they all sang along to the anthem of pharaonic promises that would come with the construction project of the Nicaraguan Canal, directly awarded by dictator Daniel Ortega to a questionable Chinese businessman named Wang Jing.

The creation of a Category 4E international airport, the generation of 200,000 direct jobs that would double the growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and the construction of two ports, one of which would be in Brito, are some of the promises made by the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship about the benefits of the Nicaraguan Canal, which, like balloons, vanished into the sky without a trace.

After more than a decade since the approval of Laws 800 and 840—laws that established the legal framework for the creation of the Canal—the project has resulted only in an annual drain on the General Budget of the Republic to finance a phantom entity and the spilling of blood of peasants and indigenous people who protested in defense of their lands.

This failure was proven after the recent reform of Law 800 and the repeal of Law 840 on May 8, 2024, which revoked the project concession from the Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Co. Limited (HKND Group).

The construction of the Canal went beyond the mega-project that would split the country in half to allow the passage of next-generation ships, according to proposals announced by official media, especially by Telémaco Talavera, who, before fleeing Nicaragua in 2018, served as the spokesperson for the National Canal Commission.

The Canal concession included seven sub-projects, among these a hydroelectric plant and a tourist complex, which, like the rest of the linked works, “would solve the difficulties faced by the population,” according to the official narrative. However, 12 years after the approval of these laws, none of these promises were fulfilled.

Infinite jobs and the end of poverty: The benefits of the Canal

The first promise of the Canal was its construction, which was supposed to generate 50,000 jobs during the first phase, 3,700 jobs for its operation, and 12,700 permanent positions by the year 2050, according to the White Paper on the Canal Project.

Additionally, in the areas surrounding the canal’s exit, between Rivas and the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCS), there would be a free trade zone, manufacturing, finance, and transportation area, which would create 113,000 jobs and more than 3,000 tourist centers. This would mean at least 200,000 jobs related to the project.

“The estimates indicate that the economic impact of the Canal would help reduce overall poverty by 11.2% and halve extreme poverty,” stated the regime’s proposal.

Although not mentioned in the White Paper, other regime spokespeople like the late Paul Oquist, executive secretary of the Canal Commission, also claimed that the project would bring 25% of the population out of informal employment. According to Telémaco Talavera, who until 2018 was also the president of the National University Council (CNU), new university programs would be opened to ensure that the technicians and engineers working on the canal would be Nicaraguan.

The National University of Engineering (UNI) commented on this in 2015 when the project was still happening. The then-dean of the Faculty of Building Technology, Óscar Gutiérrez, assured that as the Canal construction progressed, various academic offerings would be developed based on current needs.

“They promised jobs, they promised that in five years the ships would be passing through, that the GDP would double, that university programs would open. None of that happened,” says a human rights defender and anti-canal activist consulted by DIVERGENTES, who requested anonymity to protect their safety.

Mega-Ports, hydroelectric plants, and airports

The Ortega-Murillo regime also promised the construction of Puerto Brito on the Pacific coast and Puerto Punta Águila on the Caribbean coast. These ports would accommodate more than 5,100 oil tankers with a capacity of 200,000 tons each and would have 13 work vessel docks.

This included the creation of a Category 4E international airport, though the Canal spokespeople did not specify its location. This type of airport has the longest runways and the second-largest landing capacity for large aircraft. According to the regime, this airport would handle Boeing 747 and 777 and Airbus 360 planes, the largest in the world.

“A total of 565.7 kilometers of roads, highways, bridges, and other support projects. Tourist complexes along the route, some located in areas where temporary settlements for the project’s construction would be created, and other ecological centers,” continues the Canal proposal made by the dictatorship.

The hydroelectric plant would be built on the Agua Zarcas river in the Southern Caribbean Coast, simultaneously starting operations with the Canal and providing power for the locks.

According to Talavera’s interviews on official channels, this plant would also provide enough energy to irrigate up to 600,000 acres of land for agriculture, ensuring “food security” for nearby communities.

Although not included in the regime’s official Canal proposal, the spokespeople on several occasions mentioned the construction of an artificial lake similar to Panama’s Gatun Lake to guarantee a water source in case Lake Cocibolca became saline. There would also be steel mills and cement factories around the canal.

Initially, the regime assured that the works, which officially began in December 2014, would be completed in 2019, so that the Canal would be operational by 2020. However, as years passed, the dates kept changing. In 2017, the regime presented the final proposal again without setting development dates.

Twelve years of allocating millions of cordobas to the Canal

Despite the project’s complete lack of execution, the Ortega-Murillo regime allocated 65,862,000 córdobas ($2,080,159.18 according to the official exchange rate of each year) from the General Budget of the Republic (PGR) to the Nicaraguan Interoceanic Canal Authority.

The use of this amount disbursed by the Ministry of Finance between 2013 and 2024 is unknown, as the Canal project, which promised the construction of settlements along the works, does not even have its own offices, says the anti-canal activist.

The source indicates that meetings to discuss the project were held in the offices of Manuel Coronel Kautz, president of the Nicaraguan Interoceanic Canal Authority. According to Law 800, the Authority is responsible for “supervising the conservation, maintenance, improvement, and modernization of the Canal,” but after 12 years of allocations and subsidies from the PGR, it has never provided progress reports. The project doesn’t even have a website.

“It’s a ghost entity that receives money,” says the activist. “No one knows what happened to that money or what it was spent on. The State has not provided any reports on this. They promised transparency and did not fulfill it,” they say.

Meanwhile, Francisca Ramírez, leader of the Peasant Movement and anti-canal activist, also points out that there was never any work in the areas that would be affected by the canal route all this time, despite the regime claiming that the works began in December 2014.

“We saw the state’s resources being stolen while our rights were taken away. The only movement we saw in our areas was militarization and repression every time we protested against the canal until we were expelled amid the socio-political crisis,” says Ramírez.

Peasant and indigenous communities live under repression since 2013

These unfulfilled promises were the Ortega-Murillo regime’s justification for violently repressing the peasant population protesting against the Canal project and for unconstitutionally selling the canal concession to the recently bankrupt Chinese businessman Wang Jing, owner of HKND Group.

“The only thing the canal project brought us was damage and harm,” says Ramírez. Of the more than 100 peaceful marches against the Canal over at least four years, most were violently repressed by the National Police and people loyal to the regime.

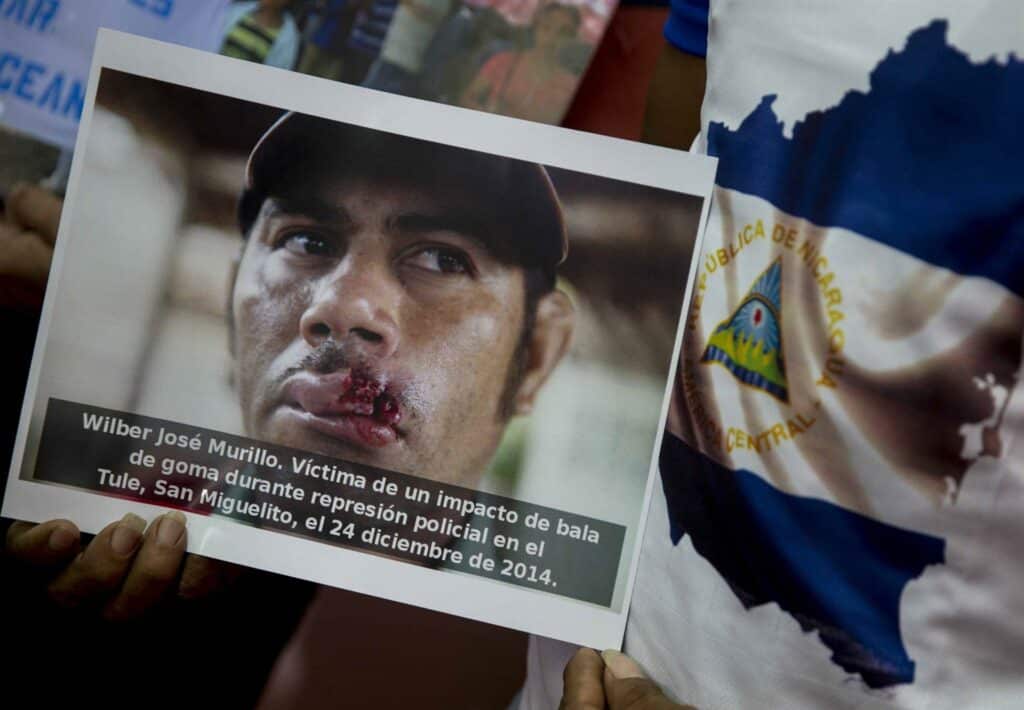

Ramírez reports that during the protests, several demonstrators were killed, people were injured with permanent disabilities, and hundreds of peasants were temporarily detained.

“There were people who were left with permanent injuries due to the repression, people who lost their eyes to rubber bullets, people who lost their organs. They were never compensated or investigated for these incidents. There was never any reparation. More than 70 peasants were detained in El Tule and transferred to El Chipote in Managua,” she recounts.

Additionally, the pressure included persecution and criminalization of peasant leaders and activists who were harassed and threatened by regime supporters. Entire communities opposed to the project, like El Tule, were excluded from state development projects, and anti-canal leaders were denied services in state institutions like health centers.

“We faced repression all the time. We had no right to submit economic development projects. Bank loans were closed to us. We were denied rights in public services like health. We were threatened during vaccination campaigns, and they entered (our communities) with an armed convoy. We lived under militarization,” recounts Ramírez.

The anti-canal activist consulted by DIVERGENTES says that the population lived with great insecurity since the approval of the laws that gave the green light to the project.

“Children would ask their parents, ‘Where will we go if the canal comes?’ Neither the parents nor the teachers could answer because no one knew. They only knew that a powerful project was coming that would displace them. At most, families would get a little money, but many peasants and indigenous people did not have legalized plots, and they would get nothing,” she says.

Reforms and repeal of Canal laws do not generate trust

The reform of Law 800 and the repeal of Law 840, which revoked HKND Group’s concession, do not yet provide relief among the peasant and indigenous populations, the activist notes. According to them, the reform of these laws is a preparation to revive the project and sell it to the highest international bidder.

“It makes us feel uncertain because we don’t know what they want to do with that project. Once again, there is no transparency, and there is no public information about it,” they say.

Ramírez points out that although it is a good thing that Law 840 has been repealed, it is not because the regime wanted it but “because they were scammed by Wang Jing.”

“They repealed Law 840 but left Law 800 to sell the concession to any investor,” she says. While the great failure of the Ortega-Murillo regime with the Canal project has been exposed, it remains a looming threat as long as they are in power.