Tomorrow at sunset I will drive to the gates of Bukele’s mega-prison and what will be, will be.

I am now in Tecoluca, in the department of San Vicente. I got up early in the morning to come to the municipality that has what the government of El Salvador has advertised as the largest prison in Latin America — in the world, some say — and I have decided not to return to San Salvador without at least trying to get close to it.

There are reasons for concern: Bukelismo is allergic to independent journalism; the area is full of soldiers and police; the country has been under a state of exception for more than a year and a half, which gives them a free pass for arbitrary detentions; and just yesterday I was held at gunpoint, restrained and threatened by a military officer when I wanted to photograph the gate of another prison, Zacatraz, as the Zacatecoluca Maximum Security Penal Center is known, located just eight kilometers from the mega-prison.

By Bukele’s mega-prison I mean CECOT, the acronym chosen for the Terrorism Confinement Center, perhaps the most emblematic work of President Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez’s first five-year term.

In El Salvador, members of Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Barrio 18-Sureños, Barrio 18-Revolucionarios and other minor criminal structures have been considered terrorists since August 2015, following a ruling by the Constitutional Chamber.

But as I said: I will go to the prison with no invitation tomorrow at dusk, when the field reporting is finished. Before that, I will visit the urban center of Tecoluca and the surrounding communities, those that saw this huge work rise from one moment to the next -as they say-. Because they have talked non stop about the thousands and thousands of presumed emeeses (MSs, members of Mara Salvatrucha) and dieciocheros (members of Barrio 18) who are inside, but hardly anything about the neighbors: workers, students, cattle ranchers, old people, farmers….

-Ever since they opened it, that river stinks, but it really stinks… the water stinks… -Fátima Alvarenga, a young farmer from the Cantarrana hamlet, one of the most affected by the shit coming from the prison, told me; I used to wash my clothes there, but now, I do it in the house.

Pollution is what most worries the neighborhood of Bukele’s mega-prison. Between today and tomorrow I will hear of dead cows from drinking from once crystalline rivers, of agricultural production undervalued in the markets, and of an unbearable stench. I will also hear heartfelt complaints about militarization, about arbitrary detentions, about the prison not even having become a source of employment, about telephone signal failures, about….

And everyone I will interview, all without exception, will tell me that they believe the worst is yet to come. The number of prisoners incarcerated is around 12,000, barely 30% of the announced capacity.

***

Using the word “mega” to refer to this prison is not just another journalistic hyperbole. CECOT is truly gigantic. The prison covers 236,000 square meters, the equivalent of five times the size of Zocalo in Mexico City. It would take half an hour to walk around it… if you were allowed to get close to it.

According to the data that the Government releases at will, it has 37 watchtowers, 11 meter high perimeter walls, seven security rings, full housing for guards, also for guard dogs, a dozen workshops for painting, making desks, making clothes, etc., technology for virtual court hearings so that inmates do not leave the facilities, and its perimeter is guarded by 600 soldiers and 250 policemen.

Bukele’s mega-prison has eight wings for prisoners, completely independent of each other, and each of them is as large as the playing field of La Bombonera, the Boca Juniors stadium. Gigantic.

It was announced that CECOT would have its own sewage treatment plant but, if it works, it works terribly. Later you will understand.

The President of the Republic himself, Nayib Bukele, tweeted that it will hold “40,000 terrorists, who will be cut off from the outside world”, but, nine months after its inauguration, the number of inmates as of October 22 was 12,149.

But beyond the numbers, perhaps the most shocking fact is that in barely eight months it was built from nothing -from nothing-, on agricultural land. It was handled in secret, but a neighbor of Tecoluca contacted me on May 13, 2022 to tell me that there was heavy machinery in that area. Bukele announced his mega-prison to the world on June 21, and inaugurated it with great fanfare on January 31, 2023. It received its first 2,000 occupants on February 24.

Designing, allocating, building and equipping a project such as CECOT is a direct consequence of the state of exception that has been in effect since March 27, 2022, which, among other powers, allows the Bukele Administration to assign contracts by handpicking.

Another relevant fact is the location: El Perical de Tecoluca. “We decided to do it far from the cities,” Bukele himself proudly announced. The chosen land was located 70 kilometers from the capital, of infinite fertility, wedged between the Chinchontepec volcano and the Pacific Ocean; a territory with countless rivers, streams and creeks, an area of water recharge.

Regarding its distance from the cities, it is true that CECOT avoided the historical tendency to build prisons in urban centers or very close to them, but El Salvador is the most densely populated country on the American continental shelf, with more than 300 inhabitants per square kilometer. The presence of CECOT is affecting thousands.

The nearest settlement, just over a kilometer away, is called El Milagro 77. I had to get there.

***

Wilfredo Escobar Portillo is 47 years old, suffers from chronic renal insufficiency, is poor and lives in El Milagro 77. The two streams that border this community to the east and west are today more voluminous and nauseating because of the raw or poorly treated fecal discharges that come down from CECOT.

-We used to catch crabs and fish here, but now, if a dog drinks the water, after a few days it gets sick and dies. It’s as if the water coming down has strong chemicals,” Wilfredo told me, next to the pedestrian walkway of the foul-smelling Perical River.

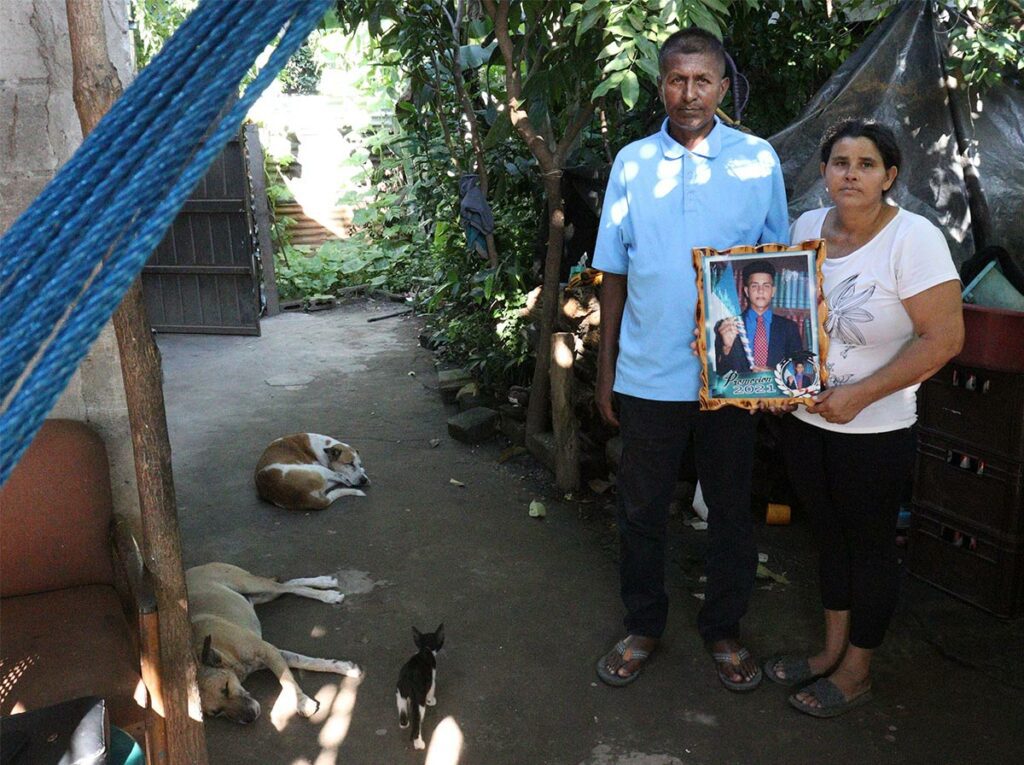

Now we have been talking for more than an hour outside his house, and he has convinced me that neither pollution nor his terminal illness – four peritoneal dialysis sessions a day – is what worries him most. Nor is it the mega-prison itself. What has been keeping Wilfredo awake at night since March 15 is the arbitrary detention of his son Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina, a young man imprisoned under the state of exception.

There are thousands of innocent people locked up by the Bukele Administration in El Salvador, but Alexis’ is one of the most unjustified cases.

At the age of 18, Alexis was already the family’s main provider. He is -was?- one of those tough young men who do not succumb to the poverty that marked their childhood. He worked as a construction worker for a contractor in Zacatecoluca – he was arrested and beaten on his way home from work -, he had saved to buy a beehive and produce honey, and to buy a modest number of chickens, breed them and sell them in the market. And all this while studying high school remotely. A young man whom it would not be difficult to describe as exemplary, but whom the Bukele government considers a terrorist.

Alexis is innocent not only because Wilfredo and Maria Norma Urbina, his mother, are telling me so. His boss, his neighbors and even the mayor of Tecoluca, who is from Nuevas Ideas, Bukele’s party, back him up. Alexis’ innocence is also supported, in a sworn statement before notary Natividad Argueta, by police agent J.F.M.G., who was assigned to the area for three years in an anti-gang unit.

Despite being warned by the notary that lying would expose him to the crime of false testimony, the anti-gang police officer was categorical: “The deponent declares that if he knew that young Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina was a member, collaborator or relative of gang structures, he would not expose himself or risk defending him, but [he does so because] he is aware and knows that he is an honest, hard-working person who respects all kinds of authorities.

Copies of this and the other exculpatory documents that Wilfredo has been compiling are known to the Salvadoran State, but as I write this chronicle, Alexis remains incarcerated and isolated in cell 33 of Sector 2 of La Esperanza Penal Center, Mariona. Eight months now.

-I was even happy when the soldiers came to the house that day to ask questions,” Wilfredo tells me, almost embarrassed.

Alexis wants – wanted? – to be a soldier. He had presented the documentation to the Armed Forces, he had passed all the filters and requirements, and at the beginning of April he expected to be called up to the 5th Infantry Brigade in San Vicente. That is why, even in spite of the state of exception, Wilfredo was happy when a platoon showed up at his house and asked for his son.

Surrealism in its purest form.

-Since the prison was built, soldiers walk past my house every day; some go down, others come up… and so on, night and day- Wilfredo tells me.

The militarization is excessive in the communities and hamlets surrounding CECOT. In El Milagro 77 — named after the kilometer of the highway where the exit is located — Alexis is not the only young man detained, despite the fact that for many years before the regime there was no gang presence. It has something to do with the fact that most of those who founded this settlement in 1998 — Wilfredo is one of them — were ex-guerrillas of the FPL, the Popular Liberation Forces.

For Wilfredo, he tells me in a sad and resigned tone, the construction of the mega-prison and the arbitrary detention of his son – which is literally consuming him – have a cause and effect relationship. This is why pollution and even his illness have taken a back seat.

Before visiting Wilfredo and other neighbors of El Milagro 77, before visiting their dead streams, I spent this Friday morning in the central park of Tecoluca. There I talked with César Cañas, a social and political activist. César is part of the MDT, the Movement for the Defense of the Land of Tecoluca, and is the candidate of the FMLN party for the municipal elections to be held in March 2024.

This young agronomist engineer has explained to me that the sudden construction of CECOT in his municipality began in a clandestine manner, without the environmental impact study required by the Environmental Law, nor consultations in the affected communities. The State did not even pay the municipality to build something like this, a multi-million dollar project.

“But the most serious thing is that it was built on the slopes of the volcano, in a water recharge zone,” César emphasized to me.

Another point that he mentioned, and that I will hear in all the interviews these two days, is that neither the works first, nor the administration of the mega-prison later, have generated jobs. It’s only a few Tecoluquenses that have benefited from a salary, among thousands of workers, custodians, administrators….

The morning conversation with Cesar happened on a park bench, while a platoon of the Armed Forces fluttered around, equipped as if they were going to fight in Gaza.

It is late and I am on my way out of El Milagro 77, a community where I have arrived on my own initiative. César has been the one who suggested to me that, in order to fully measure the impact of the contamination, I should go to the San Francisco Angulo community and the Cantarrana hamlet.

***

Félix Laínez has summoned me to his home in San Francisco Angulo at 8 o’clock this Saturday morning. The river that borders El Milagro 77 to the west is the one that 500 meters below bathes this community of Tecoluca, the closest to the municipality of Zacatecoluca.

It has not been difficult for me to find the house because everyone here -about 125 families- knows it. Felix is, in the purest sense of the word, a community leader. Born and raised in this corner of the country, he has been combing his gray hair for years; he is 55 years old.

I showed up on time, about five minutes ago, and his wife offered me water and a chair on the porch, although that word sounds pompous for this home that is rural and simple. Six meters from where I have sat, a cow grazes, and its mooing will coexist with this long conversation.

Felix now shows up sweaty and dressed for work, with wellies, a fisherman’s cap that he takes off to say hello and his knife sheathed on his shoulder. He is a farmer -corn, maicillo, beans; not rice anymore, since the price plummeted- and a cattle rancher, but on a small scale, he explains. In fact, he comes from feeding his cows… the cows he has left.

-Two of them have already died because of the water issue,” he repeats what he told me yesterday via WhatsApp.

His land is next to the now toxic river, once full of life. Beautiful crayfish used to come out, he says. Before CECOT he had 20 cows and a couple of oxen. Now he has only three cows; one of them is this one next to us. He sold the oxen last week.

Felix knows the basics of veterinary medicine, he invests in the health of his cattle and brags about having always had a robust, healthy, well-fed herd.

-The two cows that died, I left them in the paddock in the afternoon and they were dead the next day,” he tells me.

He heard of other dead cows in other communities also for having drunk from the rivers that flow down from Bukele’s mega-prison. He dug a big ditch at the beginning of the rainy season to store water, but, knowing that the dry season is upon us and he will depend on the river again, he has opted to sell them, one after the other.

He was also concerned that in the main markets, where local ranchers and farmers sell – San Vicente and especially Zacatecoluca – word has spread that everything from the area most affected by CECOT is contaminated.

-Here we have water all year round and there has always been a lot of vegetables: cucumbers, radishes, green beans, sweet peppers, loroco… But in the market for some time they have been asking where the produce comes from, and if you say it comes from 77, because that is what they tell us, they either don’t buy it or they want to take it away from you.

As a community leader, he has filed a formal complaint with the Tecoluca health unit, which depends on the Ministry of Health, but they have not listened to them; they have not even responded to his requests to analyze the water they are consuming, which is from wells, and Felix fears that all the rottenness emanating from the prison is infiltrating.

Felix is pessimistic, very pessimistic. He believes it is only a matter of time before the contamination spreads to all the land between CECOT and the Pacific Ocean. A triangle of some 300 square kilometers in which there are important population centers, such as Santa Cruz Porrillo, El Playón, Los Marranitos or San José de la Montaña.

-And it has value to be defending your community at this time, with this stunt by the regime- he tells me in a tone halfway between anger and dignity.

After an enriching conversation, I say goodbye to Felix and go to have lunch at Pollo Campestre in Zacatecoluca. As soon as I leave San Francisco Angulo and get far enough away from CECOT, all the messages and sounds accumulated during three hours fall all at once on my phone. The intermittent or non-existent signal, depending on the community and the company you have, is another of the consequences that affect the neighborhood.

After lunch, I now drive to the hamlet of Cantarrana, canton El Perical, still in Tecoluca. This settlement consists of barely thirty scattered houses, split in two by one of the pestilent rivers that flow down from Bukele’s mega-prison. There is only one access road to Cantarrana, which dies there; unpaved, of course.

Just before arriving, an old woman walks with a basket full of corn on her head; she is going to the mill. I greet her, introduce myself, ask.

-And here in Cantarrana, is the river also polluted?

-So they say. Today nobody washes there, nobody bathes there; only in the house they bathe.

In the village, there is a footbridge to cross the river. In all the communities I have visited I have been told that CECOT discharges before dawn and/or late at night; now, in the middle of the afternoon, the water runs cloudy, with patches of white foam, and the smell is strong.

On a riverside property, Fatima Alvarenga and Carlos Ernesto Pineda, 22 and 27 years old, are working in a bean field. Fatima repeats scenes I have been hearing since yesterday: pestilence, the occasional dead dog, useless water for washing….

Carlos Ernesto listens carefully a few meters away and leaves for a moment the shovel with which he is digging to say something he thinks is funny.

-Last week a watermelon seller came to Cantarrana and, as he saw the water running, he grabbed it with his hands to wash his face… Ooooff! Until he smelled it! It had happened before to others, but this one asked if he could come in to the house to get rid of the bad smell.

***

Today we are on our way to CECOT. Dusk.

I start my Kia Rio and leave Cantarrana with the feeling that, after two intense days of reporting, I have enough to write a worthy chronicle that portrays the concerns of the neighborhood of Bukele’s mega-prison. I am satisfied.

The excremental river that flows down from CECOT to Cantarrana, and from here towards the sea, is more direct, but to get by car to the prison gate is 3700 meters. Up to the first houses of San Francisco Angulo I now count one, two, three rivers and streams. Three in just 800 meters. Indeed a lot of water flows from the towering Chinchontepec volcano to the Pacific Ocean.

Just now I am passing in front of Felix’s house. “With this prison,” he told me this morning, “two things are going to happen: first, we are going to feel the contamination coming down from CECOT in the rivers; and then, our groundwater, the water we drink, will be contaminated. The first thing has already happened.

I continue in first and second gear up to the main road. Right, 200 meters to the solar plant that characterizes this landscape, I cross to the left, and I’m already on the shiny access road to CECOT.

I go with the recorder on and say this: “Let’s see what happens, but in journalism, as in life, sometimes it is better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission”.

I haven’t even gone 100 meters, and a military checkpoint: two soldiers with assault rifles in a precarious hut that gives them some shade and little else. One comes out to meet me, arm raised. I brake. I have the windows down.

-Good afternoon, can I…?

-Where are you going?

-Hello, good afternoon. My name is Roberto and I want to approach CECOT.

-You can’t.” The soldier was direct and firm.

-Nothing?

-Nothing.

-I’m doing a report on the contamination of the rivers; I come from the area of Angulo, of Cantarrana…

-But you can’t,” the soldier said firmly.

-Thank you. I’m going to go around the front.

What was bound to happen happened. I still had a kilometer to go to get to CECOT and, as it is a steep slope, I could not even see the walls or the watchtowers.

I finish the coverage in Tecoluca, San Vicente. It is getting dark. I return to San Salvador with the conviction that Bukele’s mega-prison will continue to be the talk of the town.