The Ortega-Murillo regime manages a government system that promotes the existence of “ornamental” institutions due to their lack of impact on the population, despite being key in today’s society based on their functions. These are entities whose relevance is measured solely by the constant changes in their representatives, the ineffectiveness of their public policies, and their unclear work plans. Some examples of these types of institutions are the Ministry of Women (Minim), the Ministry of Youth (Minjuve), and the Human Rights Office (PDDH), among others.

Some of these institutions have been around for just over 10 years, while others much longer, but regardless of their time in operation, little is known about their work, and they are not well recognized by the public or even other state entities.Their role has been purely propagandistic, with the aim of pretending state intervention in vulnerable populations and to repeat the dictatorship’s discourse, explains sociologist and feminist María Teresa Blandón..

The Ministry of Women, the replica of the “Co-president’s” feminism

The Ministry of Women’s (Minim) work has little or nothing to do with Nicaraguan women. In reality, it only functions as an institutional directory since all programs and policies related to women are managed by other institutions.

The real role of Minim is to be the main voice of the Ortega-Murillo regime regarding actions supposedly taken by the government in favor of women and to manage the creation of a series of informative leaflets, according to their discourse, “to empower women.”

According to Blandón, Minim “is a replica of the understanding that the co-president has on gender issues and women’s rights.” “Violence and poverty are the two main obstacles to women’s empowerment. The Ortega-Murillo regime does not have a comprehensive strategy to reduce poverty, which we know affects women particularly, nor do they have a comprehensive strategy to combat violence,” she points out.

The Ministry of Women and Femicide

“We have had 40 femicides so far this year. This regime has been in power for 17 years and had enough time to create a sustainable comprehensive strategy against violence. All they have done is create these leaflets, probably dictated by Rosario Murillo, as they reflect her words, her language, and her poor understanding of violence,” she adds.

Minim has been one of the entities with the most changes since the Ortega-Murillo regime came to power in 2007 and has had the fewest effective policies for defending the rights of women and girls. It began as the Nicaraguan Institute for Women (INIM) in 1987. However, since its creation, it was never a solid institution for the defense of women’s rights and did not have the capacity to propose laws or formulate public policies in favor of women, explains Blandón.

“INIM was always a small office. Since it was born, it was born crooked and bad. It started as an institute with very little budget and no significant presence, neither in the social nor economic cabinet. So between 1990 and 2006, during those three neoliberal and conservative governments, INIM was very weak. It basically survived on international cooperation donations,” she says.

When the Ortega-Murillo regime came to power, there was a wave of layoffs and dismissals of different institution heads, and INIM was no exception.

Dictatorship “Purged” INIM for Political Reasons

“The Ortega government fired all the staff at the institute who had minimal experience in the subject and put in people who had absolutely no training or education in human rights, much less women’s rights,” Blandón recounts.

The executive director of INIM when Ortega came to power was María Ester Vanegas. She was dismissed on January 3, 2007, along with another dozen people. Vanegas had only been in office for five months during the administration of former president Enrique Bolaños and had just presented the National Gender Equity Program, the first significant proposal from INIM, which was ultimately discarded by the Sandinista regime.

Vanegas’ dismissal was just the beginning of constant personnel and leadership changes in this institution. Her replacement was Emilia del Carmen Torres Aguilar, who was also removed from the position after three months. The next appointment was Rita del Socorro Fletes Zamora, who was dismissed after five months and replaced by Claudia Fátima Cerda López, who remained in office until December 2008.

In other words, there were three dismissals and appointments in 2007 alone, and in total, there were seven more changes in representatives from that year until 2012 when INIM was elevated to the status of a ministry.

A simple propaganda tool

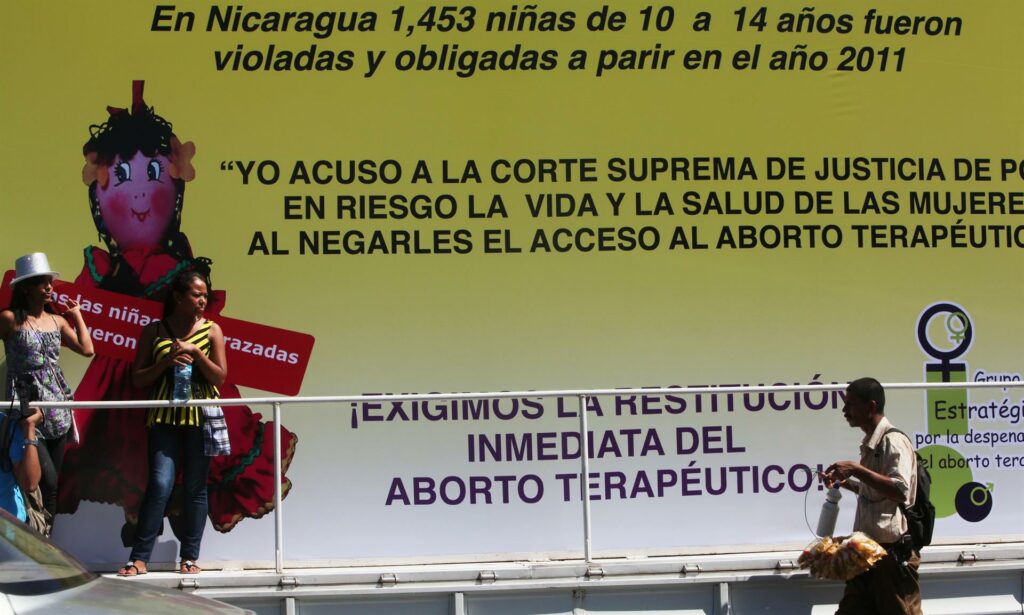

Although one of INIM’s functions was the defense of women’s rights, the institution did not intervene when the Ortega-Murillo regime amended laws that violated women’s rights, such as the repeal of medical abortion, which allowed women access to abortion when the pregnancy put their lives at risk.

“They started functioning as the government’s propaganda team. They remained silent about everything that happened during Ortega’s first term, like the absolute ban on abortion. It was as if they didn’t exist. Occasionally, they held a fair to talk about HIV or breastfeeding, but nothing more,” Blandón recalls.

A couple of years later, INIM lost international cooperation donations — which had decreased since the absolute ban on abortion in 2007 — due to its lack of diligence in defending and promoting women’s rights. It also began a policy of citizen exclusion characteristic of the Ortega-Murillo regime: it closed all doors to dialogue, alliances, and collective work with women’s organizations. “The directors were even forbidden to meet with feminist organizations,” Blandón notes. Its institutionalization crumbled quickly, she adds.

In 2013, INIM was elevated to ministerial status through Law 832, Law of Reform and Addition to Law 290, Law of Organization, Competence and Procedures of the Executive Power, and was renamed the Ministry of Women (Minim). However, the change was in form but not in substance, as there was no variation in its actions.

12 directors and ministers in recent years

From 2007 to 2024, there have been 12 heads of this entity: seven directors while it was an institution and five ministers since it became a ministry. That is, they only managed to stay in office for an average of a year and a half. The longest-serving minister was Jessica Yaoska Padilla, who was in office for almost five years. On May 13, she was dismissed to be appointed ambassador to the Dominican Republic, a position unrelated to her functions within Minim. The new minister is Tamara Vanessa Martínez, an Ortega-supporting singer who graduated in Social Work from the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNAN-Managua).

Most of these heads did not have a curriculum focused on gender issues nor had they worked with the female population. They also failed to fulfill their obligations to represent the state in international agreements related to women’s rights to which Nicaragua is a signatory, nor did they report on the situation of women and girls in the country during their presence in conventions and other meetings.

“They were appointed to repeat Ms. Murillo’s discourse. They didn’t even know what international conventions the Nicaraguan state had to comply with. They didn’t participate in the Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean of ECLAC to follow up on the Montevideo Consensus. They didn’t submit reports every four years for the Universal Periodic Review of CEDAW,” explains Blandón.

In fact, in the last session of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) held in October last year, the Committee experts requested Nicaragua’s expulsion “for doing nothing to protect Nicaraguan women.”

PDDH, an institution silent on human rights violations

The facade work, as Blandón calls it, is not exclusive to Minim. The Office of Human Rights (PDDH), an institution created for the “promotion, defense, and protection of constitutional guarantees” of Nicaraguan citizens, has very little to do with its origin.

Although initially, the PDDH’s work was assertive in defending human rights, like other governmental entities, its independence was quickly co-opted by the Ortega-Murillo regime.

“Between 2007 and 2011, it had a certain assertiveness. It was well recognized by United Nations human rights mechanisms. They participated in those meetings and presented alternative reports, which was their job. The fact that there was an office for prisoners, for women, for sexual diversity, among others, made it seem like it was a strengthened institution,” she explains.

However, this institutional strength did not last long. The PDDH closed all dialogue with civil society, with which it worked jointly until the Ortega-Murillo regime came to power. It also stopped reporting on its work and distanced itself from international human rights bodies due to criticism of its increasing lack of assertiveness.

“Despite being a decentralized entity, it gradually lost credibility, both in Nicaragua and within the United Nations system itself. The delegates would attend meetings and instead of reporting on the rule of law in Nicaragua, they defended the government and supposedly ‘debunked’ the human rights violation reports made by organizations,” Blandón indicates.

PDDH no longer accepts public complaints

Currently, the PDDH’s work is quite similar to that of Minim: conducting house-to-house visits to deliver informative leaflets filled with Ortega’s propaganda, among countless other topics. The protection of citizens’ rights is a task they abandoned long ago.

Although the PDDH has an online care guide, and in theory, a visit to its offices would suffice to file a human rights violation complaint, they very rarely respond to these complaints, and its actions depend on the orders of the delegates.

In 2018, the PDDH rejected complaints from the families of people killed or injured during the anti-government protests in 2018 but accepted those against “tranqueros” and “coup plotters” (as they called the protesters). These complaints were prepared by the dictatorship’s propaganda system with the complicity of this institution.

Lying to the LGBTQ+ community

Its delegates have been accused of lying to the public about proposed laws they announced but never fulfilled. For example, Samira Montiel, Special Attorney for Sexual Diversity, claimed in 2013 that she was preparing a Gender Identity Law. However, when sexual diversity organizations insisted on presenting the bill, Montiel did not do so. After eleven years, this law has never materialized.

“She said she couldn’t present the project because she didn’t want conservative groups to attack the initiative, but that was a lie. There was never an initiative,” Blandón says.

Similarly, the special women’s attorneys, who were Deborah Grandison until 2019 and Yahoska Rivas at present, also closed ranks against women’s organizations and ignored their complaints when Law 779, the Comprehensive Law against Violence against Women, was reformed on multiple occasions.

“During Ortega’s first term, we (feminists) thought we would have an opportunity to dialogue, coordinate, and collaborate with the attorney for women at that time (Deborah Grandison), but we quickly realized they were prohibited from having any contact with women organizations, just like Minim,” she notes.

The unknown Ministry of Youth

The Ministry of Youth (Minjuve) is one of the least known within the state apparatus. The institution was created in 2013, and its programs focus on youth participation, training, and education, according to the budget allocations from the Ministry of Finance. However, in reality, it is just an extension of the dictatorial arm of the Ortega-Murillo regime and the Sandinista Youth.

Its most recent significant work is promoting “Reinas Nicaragua, Embajadora de Amor a Nicaragua,” a beauty pageant created by the Ortega-Murillo regime after persecuting and criminalizing the former Miss Nicaragua director and her family, Karen Celebertti. From the call for participants to the latest updates, Minjuve has been the most prominent promoter of this event.

Before this activity, its work was mainly focused on the National Scholarship Program. These scholarships are characterized by the requirement to write a scholarship request letter addressed to “Commander Daniel Ortega” and are highly politicized in terms of selecting beneficiaries.

Minister Lucien Nahima Guevara Agüero was chosen for the position on April 20, 2022, making her first public appearance then. Prior to that, there is no information about her training or work with the youth population. Like Minim, personnel and representative dismissal has been a constant in Minjuve.